江戸末期にヨーロッパとの交易が開始されたとき、輸出された陶器などの「緩衝材」として浮世絵の印刷失敗品が使われ、それを受け取った西洋人が緩衝材・浮世絵のカラー印刷のレベルの高さに驚かされたことをきのう書いた。それくらい当時のニッポン社会では日常的な「大衆芸術」であったことそのものに西洋は驚愕したのだという。

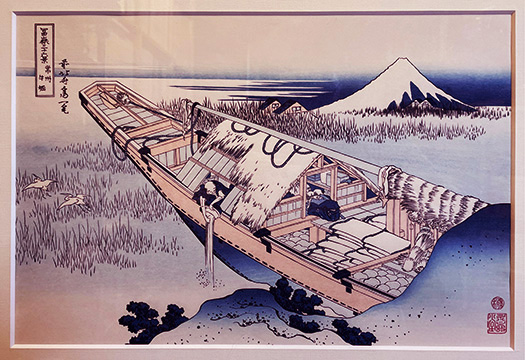

では当時の社会ではどれくらいで浮世絵は流通していたのかと探るとなんと「そば1杯」の値段とほぼ同価格帯だったという。現代のそばの値段、おおむね4-500円から高くても1,000円はしない。わたしは東京博物館で浮世絵展があったときに手刷りの限定100枚っていうのを1枚30,000円くらいで購入した記憶がある。(1枚目の写真)あれは「暴利」だったのかと唖然とした(笑)。まぁ冗談。江戸期のように大衆が支持して大量販売の事業構造が確立した時代とは違って、専門職としての「摺り師」さんの存在を支える市場構造が現代にはない。そういう時代に当時と遜色のない仕上げ技術で丹念に仕上げる職人技に惚れ惚れとしたものだ。

しかしそば1杯の値段でこういうカラー印刷の芸術を楽しめていたというのは、まことに素晴らしい。国の豊かさというのはいろいろな測り方があると思うけれど、キビシイ大衆の選別眼というふるいに掛けられた上で愛されてきた価値感には深く頷かされる。日本は「民主的」な社会の素地が根強いとわたしには思えるのですが、世界のなかでもここまで大衆芸術がリスペクトされる社会というのはすごい。西洋人が驚いたことの実質にこういう要素が強かったのではないか。「ひょっとするとこの国の民は民主主義ということを深く理解しているのはないか?」と。

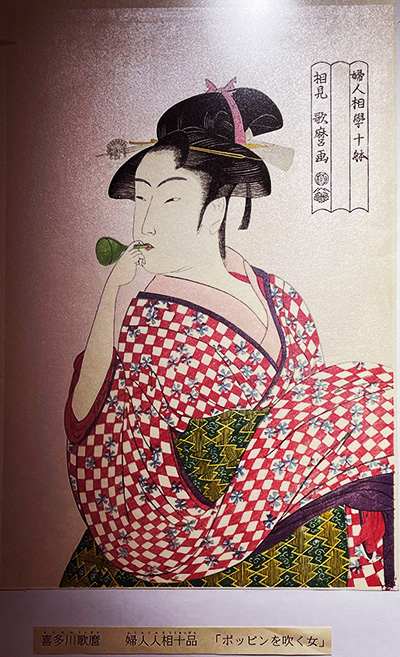

さてそういう浮世絵の題材として、全国旅行ブームを支えた「名所図会」と同時に「美人画」というジャンルが大きかったとされる。とくに江戸は常に適齢期男性が過剰な町であり、見返り美人とかたくさんの日本女性の美が追究された。で、判で押したように「うりざね顔」の美人画が好まれたようだ。現代に残っている美人画では圧倒的に多数派。以前ブログで縄文の美人、弥生の美人というような分析を試みたけれど、そこではそれほど「うりざね」への固執は見られなかった。京美人という王朝美学でもそう感じられず、むしろ「ふっくら」系への支持が強いと感じられる。そういう変遷を経て江戸期の日本的な美感としてこの「うりざね顔」はDNA的に響いてくる。江戸期の大衆芸術では民のコアを探らなければ「売れない」というキビシイ選別眼にさらされ、その結果選び取られた美感なのだろうか。さらにファッションの要素でも浮世絵には「当世ぶり」表現が競われたに違いない。現代の芸能ビジネスが行っているような切磋琢磨、熾烈な競争原理がそこに反映もしていると思う。

English version⬇

Ukiyoe: Distribution at the Price of a Cup of Soba, Ukiyoe-2: Edo Period, Boso Machiya-11

Ukiyo-e is an art form of mass printing that is supported by the masses. The strict selection of the common people in the Edo period nurtured the Japanese publishing culture. …

When trade with Europe began at the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), Ukiyo-e prints were used as “buffer materials” for exported ceramics, etc. I wrote yesterday that Westerners were surprised at the high level of color printing of Ukiyo-e as buffer materials. The West was astonished at the fact that Ukiyo-e was such an everyday “popular art” in Japanese society at that time.

I asked how much Ukiyo-e were sold in those days, and found that the price was almost the same as the price of a bowl of soba (buckwheat noodles). The price of a bowl of soba today is generally 4-500 yen, or at most not more than 1,000 yen. I remember buying a limited edition of 100 hand-printed ukiyo-e prints for about 30,000 yen each when the Tokyo Museum held an exhibition of ukiyo-e prints (first photo). (The first photo) I was stunned to think that it was a “wild profit” (laugh). Well, just kidding. Unlike the Edo period, when the business structure of mass sales was established with the support of the masses, today there is no market structure to support the existence of “printers” as a profession. I was fascinated by the craftsmanship of the “surishi” who painstakingly finished their work with finishing techniques that were on par with those of that era.

It is truly wonderful that people were able to enjoy this kind of color printing art for the price of a bowl of soba (buckwheat noodles). There are many ways to measure a country’s wealth, but I can’t help but nod in agreement with the sense of value that has been preserved and loved by a selective and demanding public. I believe that Japan has a strong foundation of a “democratic” society, and it is amazing to see a society in which popular art is respected so much, even in the world. I think this is one of the reasons why Westerners were so surprised. I think that the people of this country have a deep understanding of democracy. And.

The subjects of ukiyoe include “Meisho Zue” (famous places), which supported the nationwide travel boom, and at the same time, “Bijin-ga” (portraits of beautiful women), which was a major genre. Especially in Edo, where there was always an overabundance of men of the right age, many Japanese women’s beauties were pursued, such as the beauty of a “kirika-bijin” or “turned-around beauty. As a result, it seems that “urizane-faced” bijinga were favored, as if by seal of approval. This is by far the majority of beauty paintings that remain today. In a previous blog entry, I attempted to analyze Jomon beauties and Yayoi beauties, but I did not find much adherence to the “urizane” face. Even the dynastic aesthetic of the Kyo-bijin, or Kyoto beauties, did not seem to be so obsessed with the “plump” type. After such a transition, the “urizane face” resonated in the DNA of the Edo period as a Japanese aesthetic. In the popular arts of the Edo period, artists had to be selective in order to find the core of the populace or they would not sell well. In addition, ukiyo-e must have competed with the fashion element for “zeitgeist” expression. I believe that this reflects the principle of friendly competition and fierce rivalry that exists in the entertainment business today.

Posted on 1月 18th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.