さすがに高齢期の進行からか、最近は疲れが溜まって来やすいのか(泣)。

「四百年間のいのちの履歴書」というような長大テーマを整理整頓させるとともに、一種の「ドラマ」を脳裏に展開させながら推理をたどらせる作業では、いろいろ脳内が刺激されて、興奮状態になるのでしょうか。一方で孫の子育てではカミさんが中心になって活躍してくれるのですが、その体調管理みたいな部分での「目くばり」も夫としての務め。もちろん体力が必要な部分については引き受けることになる。それも臨機応変。千変万化する役割内容。

ということで時間が取られて、体調は知らず知らず、疲れが溜まるのでしょう。

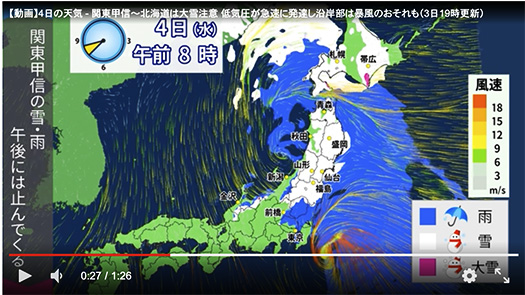

昨日はそういう時間の「すき間」3時間ほどができたので、雪融けも進んでいる石狩港方面へ。

以前はよく通っていたのに、最近すっかり縁遠くなっていた温泉入浴。札幌近郊にはいろいろな温泉がありますが。こちらは植物由来のモール温泉。

久しぶりに入ったので、低温から徐々にはじめて高温湯、露天、サウナと浸りきった(笑)。

まず入浴感のいごこちの良さに驚かされた。タイトルに書いたような「バラバラ感」であります。モールの良い香りがカラダを包んでくれて、その芳香と適度な湯温、はじめはゆったりさせて、徐々に体の芯にまで、ちょうど骨の髄まで届いてくるような湯のあたたかみが染み込んでくる。

景色は、春の雪融け風景の北海道日本海側の温湿度感を視覚化して染み込んでくる。

これはまさに疲労感バラバラであります(笑)。

・・・ということで、かみさんを迎えに戻ったのですが、その送迎作業繰り返しを終えて、家に戻ったら、バタンキュー一択。午後5時頃から完熟睡8時間ほど。

最近はどうしても夜間就寝中1度は起きてトイレするのですが、昨日はまったくの8時間熟睡。

それで途中だった作業の続きをしていてふたたび睡魔の降臨、午前3時過ぎから6時までの「2度寝」にたっぷりと落ち込んでおりました。

写真はその温泉名物の「カピバラ」君であります。ありがとね。

<どうも宣伝っぽい記述内容でしたが、そういう意図は全くありません、念のため。>

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【First time in ages at Mall Hot Springs—my bones feel like they’re falling apart (lol)】

Is this unexpected level of “accumulated fatigue” really hitting me? The famous Capybara-kun gave me a divine nudge, like, “Hey, take it easy for a bit” (lol)…

I suppose it’s the progression of old age, but lately I’ve been getting tired more easily (sigh).

Organizing such a vast theme as “a four-hundred-year life resume” while simultaneously unfolding a kind of “drama” in my mind and following the deductions—perhaps all this stimulation is sending my brain into overdrive. On the other hand, while my wife takes the lead in raising our grandchild, keeping an eye on her health management is also my duty as a husband. Of course, I take over the physically demanding parts. That too requires flexibility. The roles are ever-changing.

So, time gets taken up, and before I know it, fatigue builds up.

Yesterday, I found a three-hour “gap” in that busy schedule, so I headed toward Ishikari Port, where the snow is melting.

I used to go often, but hot spring bathing had become a distant memory lately. There are various hot springs near Sapporo. This one is a plant-derived moor hot spring.

Since it had been so long, I started with the low-temperature bath, gradually moved to the hot bath, then soaked in the open-air bath and sauna (laugh).

First, I was amazed by how pleasant the bathing experience felt. It’s that “fragmented sensation” I mentioned in the title. The pleasant aroma of the moor enveloped my body. That fragrance, combined with the just-right water temperature, started off relaxing me, then gradually seeped in, warming me right down to my core, like the heat was reaching deep into my bones.

The scenery visually evoked the warmth and humidity of Hokkaido’s Japan Sea coast during spring snowmelt, seeping into my senses.

This truly shattered my fatigue (laugh).

…So, I went back to pick up my wife. After finishing that shuttle run, I returned home and collapsed. From around 5 PM, I slept soundly for about 8 hours.

Lately, I inevitably wake up once during the night to use the bathroom, but yesterday I slept soundly for a full eight hours.

Then, while continuing some work I’d left unfinished, the sleep monster descended again, and I sank into a deep “second sleep” from past 3 AM until 6 AM.

The photo is of the hot spring’s famous “Capybara” guy. Thanks, buddy.

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 3月 13th, 2026 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類 | No Comments »