さて「四百年間のいのちの履歴書」シリーズに徐々に復元努力。

400年間にわたっての血脈の生き様の解明となると、さすがに心理的に興奮が高まらざるを得ない。手法としてはどうしても「父系」をたどるのがわかりやすい。父母両系をたどるとなると幾何級数的に拡散してしまって、すぐに全人口を上回ってしまうのだという。

その点、父系一系の場合には絞り込めて、それも「代数」で個人まで特定できるので過去のその人生にまで思いを至らせることが可能になる。DNAが近しいことから心理まで慮りやすい。

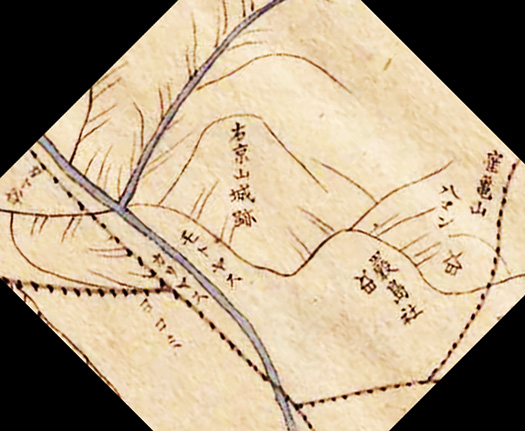

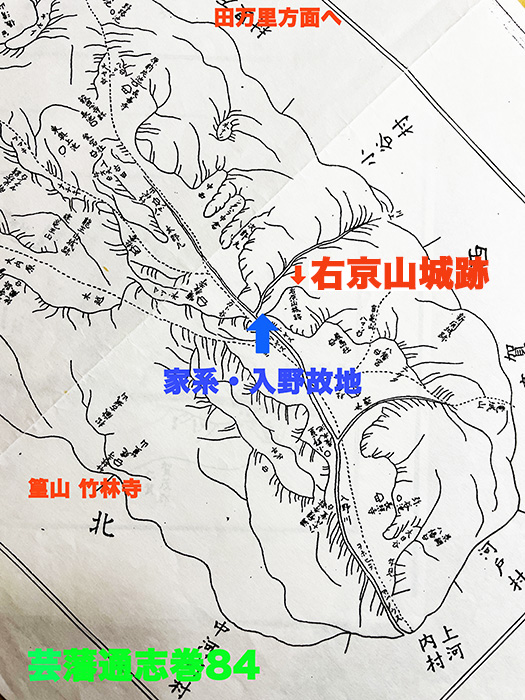

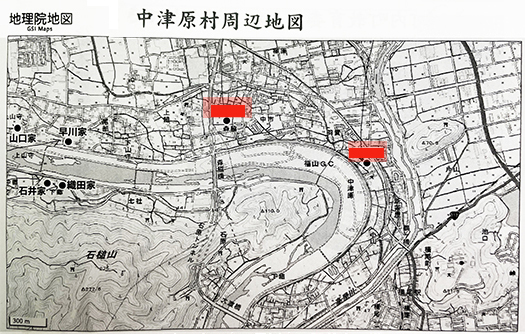

わたしの家系ではわたしを1代として数えて6代前の祖先が、この広島県福山市の北方4-5kmの、芦田川が石鎚山周縁を回り込むこの中津原地域に深い因縁がある。その後も3代前の祖父も、この地域の家に嫁さんの由縁がある。

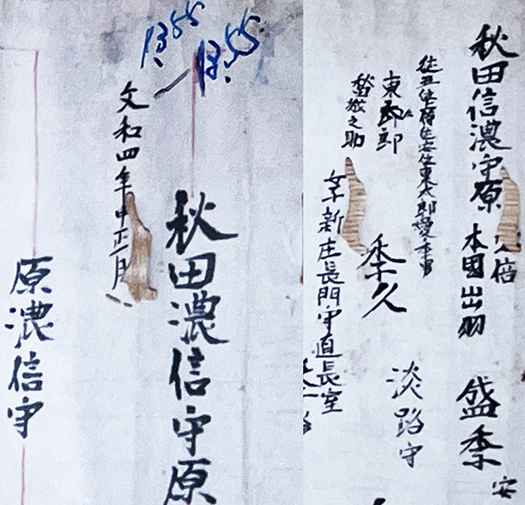

6代前の祖先は7代の父が尾道の商家を8代の祖父から継承して営みながら、なんと28歳の若さで他界してしまい生後1歳で母に連れられ、この中津原の母の実家に移ってきている。そこで育ちこの地で生まれた女性と婚姻した。その上で祖母の兄・大伯父の家が福山市今津町で「本陣」を務めていた家に「世話に」なっている〜まぁ「手代」として現代風に言えば「就職」したと言えるだろうか。

1歳の小児を育て上げてくれ、しかも母系の縁から嫁取りまでさせてもらったワケだ。

つくづくと母性のありがたさを感じさせられる。それも祖母+母という2代の母性。

先述したように父系でたどるのがわかりやすく絞り込みやすいけれど、しかし一方で男性の人生は、母系の「母性」に導かれていると思える。深い愛情。

昨年11月にこの地を訪れたときの風景写真が、ずっと残響し続けてならない。

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【The Land of Nakatsuhara: Birthplace of My Sixth-Generation Ancestor’s “Mother and Bride” ~ Echoes of Motherhood】

A landscape deeply embedded in my family history. The land where my sixth-generation ancestor was raised, and where his bride was raised too. Echoes of motherhood. …

Now, gradually restoring the “Four Hundred Years of Life’s Resume” series.

Unraveling the lived history of a bloodline spanning four centuries inevitably stirs intense psychological excitement. Methodologically, tracing the paternal line proves far clearer. Tracing both parental lines leads to exponential dispersion, quickly exceeding the entire population.

In contrast, focusing solely on the paternal line allows for narrowing down the scope. Moreover, using “generations” enables identification down to specific individuals, making it possible to contemplate their past lives. The closeness of DNA also makes it easier to consider psychological connections.

In my family line, counting me as the first generation, my ancestor six generations back had deep ties to this Nakatsuhara region. It lies 4-5 km north of Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, where the Ashida River curves around the base of Mount Ishizuchi. Later, my grandfather three generations back also had connections to this area through his wife’s family.

My sixth-generation ancestor inherited a merchant house in Onomichi from his grandfather. Tragically, he passed away at the young age of 28. At just one year old, he was brought by his mother to her family home in Nakatsuhara. He grew up there and married a woman born in this very place. Furthermore, he came to work at the home of his grandmother’s brother—his great-uncle—in Imazu-cho, Fukuyama City, a house that served as a “honjin” (main inn for travelers). He was taken in to “help out”—well, in modern terms, perhaps you could say he “got a job” as a clerk.

They raised him from a one-year-old infant, and moreover, through this maternal connection, they even allowed him to marry into the family.

It makes one deeply appreciate the grace of motherhood. And that of two generations—grandmother and mother.

As mentioned earlier, tracing the paternal line is clearer and easier to narrow down. Yet, at the same time, a man’s life seems guided by the maternal love of his mother’s lineage. Deep affection.

The landscape photos I took when visiting this place last November continue to resonate within me.

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 1月 25th, 2026 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類 | No Comments »