昨日、札幌に帰還いたしました。

ここ最近、移動時の「インバウンド」ぶりがさらに加速、ドライブが掛かっている。観光地で聞こえるのは、外国語ばかり。上野を中心に宿泊することが多いのですが、写真の不忍池で早朝散策していても目にするのは外国人多数。一時期のチャイナオンリーではなく、欧米系中心かなぁという状況。

ランチなど飲食店でも日本人からの接遇を受けることの方が希少機会。

日本の「少子化」状況を受けて労働力の確保という抜き差しならない必要性から、実質的な移民政策が取られている証明か。国際金融での「円安」進行もこうした要因を反映して「そうしやすい環境」を意図的に作り出しているようにも思える。このままアメリカのように「多民族化」していくことが趨勢と言えるのでしょうか?「経済政策」の根幹テーマとしてきちんと論じて欲しい。

参院選での参政党の伸展要因は「日本人ファースト」という理念が広範に日本人意識に芽生えつつあることの証明とも考えられる。

たしかに移動しながら感じるのは多民族化への自分自身の内心での化学反応。

どうもこれまでの日本社会とは大きく様相が変わってきている、と。

一昨年、京都に行っていてあまりのインバウンドぶりに内心、悲鳴を感じて「まだマシ」な奈良方面それも「なるべく外国人がまだ来ない」地域として飛鳥や橿原に行動しておりました。「より日本的なるもの」にこころが向かっていくのは自然でしょう。

・・・ということで池のほとりでたわむれているカモたちを観察していると、しかし実にその品種は多様だと気付かされる。わたしがいつも散歩している札幌円山公園ではほぼ1種類のカモとオシドリという近縁種だけですが、どうもカモといっても多様だと驚いた。まぁきっと昔からそうなんでしょうが、池の畔の「説明板」には以下の記述。

「不忍池にはいろいろなカモ(中略)が多いとき1万羽を超えることも。キンクロハジロ、ホシハジロ、オナガカモがベスト3。カルガモ、ヒドリカモ、バン、ハシビロカモ、マガモなど・・・」

なんだそうであります。

多民族化というのは、日本列島という交流の多い環境では自然な流れなのでしょうか。幕末明治の変動もこの列島社会では「受け入れやすい」から、アジアで先駆けたということなのかなぁ。

●お知らせ

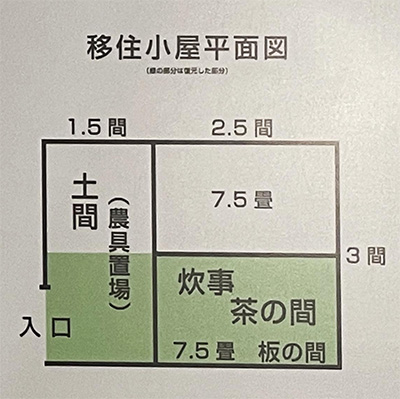

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Ueno’s Shinobazu Pond Ducks and Multicultural Japan】

A classic Tokyo stroll. What catches the eye is the ducks’ “diversity.” Quite different from Sapporo in “feather color.” But no Mandarin Ducks. I wonder if they don’t get along…

Yesterday, I returned to Sapporo.

Recently, the “inbound” trend during travel has accelerated even further, gaining momentum. All you hear at tourist spots is foreign languages. I often stay around Ueno, but even during early morning strolls around Shinobazu Pond (pictured), I see mostly foreigners. It’s no longer just Chinese tourists; it seems more Westerners are coming now.

Even at lunch spots and restaurants, receiving service from Japanese staff has become a rare occurrence.

Is this proof that Japan is effectively implementing immigration policies, driven by the urgent necessity to secure labor amid its declining birthrate? The ongoing weakening of the yen in international finance also seems to reflect these factors, as if intentionally creating an environment conducive to such trends. Is it inevitable that Japan will follow America’s path toward becoming a “multiethnic society”? I wish this core theme of “economic policy” would be properly debated.

The growth of the Japan First Party in the Upper House election could be seen as proof that the “Japanese First” ideology is taking root in the consciousness of many Japanese people.

Indeed, as I move around, I feel my own inner reaction to this multiethnic shift.

It seems Japan’s society is changing significantly from what it was before.

The year before last, while in Kyoto, I inwardly screamed at the overwhelming influx of tourists. I headed for the Nara area, which felt “still bearable,” specifically to places like Asuka and Kashihara, hoping to avoid areas still largely untouched by foreigners. It’s natural for one’s heart to gravitate toward “more Japanese things.”

…And so, observing the ducks frolicking by the pond, I realized just how diverse their breeds actually are. At Sapporo’s Maruyama Park, where I always walk, there’s basically just one type of duck and its close relative, the Mandarin duck. But I was surprised to learn that ducks themselves are quite diverse. Well, I suppose it’s always been that way. The information board by the pond reads:

“Shinobazu Pond hosts various ducks (omitted)… sometimes exceeding 10,000 birds. The top three are the Common Pochard, Tufted Duck, and Long-tailed Duck. Others include the Spot-billed Duck, Gadwall, Common Moorhen, Shoveler, Mallard, etc…”

So it seems.

Is this multiethnic trend a natural progression in the Japanese archipelago, an environment rich in exchange? Perhaps the upheavals of the late Edo and Meiji periods were “easier to accept” in this island society, making Japan a pioneer in Asia.

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 9月 29th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類 | No Comments »