さて一段落させて、ふたたび「元寇」シリーズ復帰。

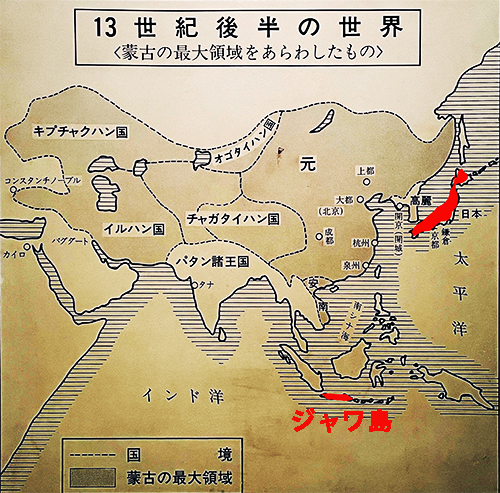

前後2回に及んだ元と高麗の軍船団による九州北部への侵攻。東アジア世界においては中国大陸が中華としていわば中枢の位置を占めているけれど、そこでの戦いはいかにも「大陸」的な陸上戦的な権力抗争であって、その周辺の国家社会にとってそうした国家は交易の対象であって、さまざまな文化的な往来交流が基調的な関係性ということになる。そのなかでも最大の「交易」国家として日本列島社会が存在してきた。海を挟んでの社会同士の関係としては、そうなるのが自然だろうし、事実日本社会は、大陸国家との関係で経済文化そして、政治制度などでも交易的にそれらを受け入れてきた。

この元寇の時代は以前からの「日宋関係」という活発な交易が対「南宋」間で継続的に展開していた。日本側からは旧・奥州藤原氏の支配地域から産出する黄金が輸出されていた。日宋交易では日本側からは金・真珠・硫黄・木材などが輸出され、宋からは香料・錦・磁器・書籍などが輸入されていた。この鎌倉期には禅の人材や文化などの輸入が活発だった。多くの禅僧が渡海してきている。

そのなかでも大陸国家にとっては金の魅力が絶大だったとされる。当時の金と銀の交換比率が日本では1:5なのに大陸国家では1:13という現実があった。「日本からは金が安く入手できる」というのが、最大の関心事だったことがわかりやすい。マルコポーロはこの時代人であり元の皇帝・フビライにも謁見しているが、その「黄金の国ジパング」の想像力は共有されていたと思われる。

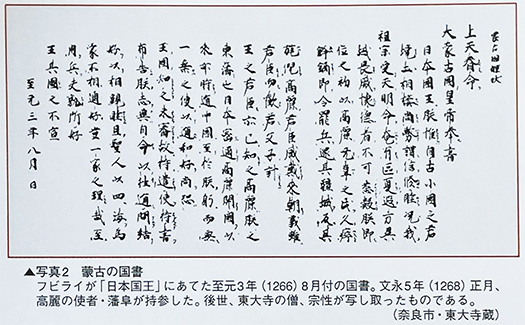

上の写真は元から日本側に送られた「国書」。最近の文書研究では元の皇帝が送った国書としては「前例のない鄭重さ」と解されている。国書冒頭に、日本国王に対して「奉る」とあり礼を尽くしている。さらに文末に「不宣」の文字があることが注目されている。これは「友人間」の定型句であってなお「臣下」としない意思を示した語句だと蒙古の文書「経世大典」に明記されているとのこと。

また受け取った国書に対して、それを翻訳解釈したと考えられるのは当時の社会での「大学教授」=禅宗高僧たちだろうが、かれらは「宋」から渡って来た人々であり、漢文の解釈に当たって元に対して否定的だった可能性が非常に高いと思われる。

国書では「武力を使いたくはない」という表現もあったとされている。元の派遣軍・指揮官たちにはこうした「戦略」判断が大きなウェートを占めていたのではないか。そう考えてくると、第1波の文永の役で一定の打撃を与えたことで戦略的「役割」は終わったと考えた可能性が高い。多数の軍船団が狭い博多湾にビッシリと集結している中、荒天も予測されるような状況。早期に撤収という方針に決したと考えられる。文永の役での撤収に「神風」は無関係で意図的な撤収だったのだと思われる。

English version⬇

[Yuan’s ‘Statements of State’ and World Affairs Yuan Enemy History Museum – 6]

The latest research interprets this as unprecedented zhengjing as a world state. Even a friendly call. Yuan’s strategy at the time of the Wen-Yong War was a friendly attitude. Is kamikaze irrelevant? …

Now that we’ve put a stop to this, we’re back to the “Genko” series.

The invasion of northern Kyushu by the Yuan and Koryo fleets, which took place twice before and after the invasion. In the East Asian world, the Chinese continent occupies the central position as China, but the battles there were land-based power struggles in a ‘continental’ style, and for the surrounding states and societies, these states were objects of trade, and various cultural exchanges were the key relationship between them. The Japanese archipelagic societies have been the largest “trading” states among these. This is a natural relationship between societies across the sea, and Japanese society has, in fact, accepted trade in economic, cultural and political systems in relation to continental states.

In the period of the Genko Incident, active trade between Japan and the Southern Song dynasty (960-1279) had been ongoing. From the Japanese side, gold produced from the former Oshu Fujiwara clan-controlled areas was exported. In the Japan-Song trade, gold, pearls, sulphur and timber were exported from the Japanese side, while perfumes, brocade, porcelain and books were imported from the Song. Imports of Zen personnel and culture were active during this Kamakura period. Many Zen monks travelled to the sea.

Among these, it is said that gold was immensely attractive to the continental states. The exchange ratio of gold to silver at the time was 1:5 in Japan, but 1:13 in the continental countries. It is easy to see that the main concern was that ‘gold could be obtained cheaply from Japan.’ Marco Polo was a man of the period and had an audience with the Yuan emperor, Hubilai, whose imagination of the “golden land of Zipangu” seems to have been shared.

The photo above shows the “Kokusho”, a letter of state sent from Yuan to the Japanese side. Recent research into the document has shown it to be ‘unprecedentedly Zheng-weight’ for a state letter sent by the Yuan emperors. The first sentence of the Kokusho states that it is ‘dedicated’ to the King of Japan, which is an act of courtesy. Furthermore, it is noted that at the end of the text there is the character ‘Fusen’. The Mongolian document “Keisei Dajiten” clearly states that this is a standard phrase for “between friends” and indicates the intention not to treat the person as a “vassal”.

The people who are thought to have translated and interpreted the Kokusho are thought to have been the “university professors” of the society of the time, i.e. the high priests of the Zen sect, but they were from the Song dynasty, and it is highly likely that they were negative towards the Yuan when interpreting the Chinese text.

In the Kokusho, it is said that they expressed that they did not want to use force. Such “strategic” judgements may have been of great importance to the Yuan’s dispatched forces and commanders. In this light, it is highly likely that they considered their strategic “role” to have ended with the first wave of the Bunyong War, which dealt a certain amount of blows. With a large number of military convoys tightly concentrated in the narrow Hakata Bay, and stormy weather predicted, the situation was such that they were likely to have decided on a policy of early withdrawal. It is thought that they decided on a policy of early withdrawal. It is thought that the “kamikaze” had nothing to do with the withdrawal from the Bun’ei no Yakuwari, and that it was a deliberate withdrawal.

Posted on 5月 7th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.