さて今週はわたし自身の環境が大きく変わったことで、その節目としてのさまざまな整理整頓が続いています。が、ブログとしては徐々に通常の「人と住まい」というテーマでの深掘りに復帰したいと思います。

長年住宅の取材にベースを置いて生きてきたので、習いが「性」になったのでしょうけれど、建築としての住宅とその住まい手との相関関係ということが基本的な興味分野なのですね。通常の雑誌的な住宅取材で経験してきたことの体験記憶がもとにあって、そこから住まい手の生き方、暮らし方に興味が深まっていく。

そんな経験をしてきて、いろいろな機会を捉えて全国の住空間を見ることがライフワーク化している。

これまではメディア企業としての運営・活動がメインだったわけですが、今回の環境変化からもうちょっと自由度を高めて、この個人的な興味分野を掘り下げていきたいと思っています。よろしく。

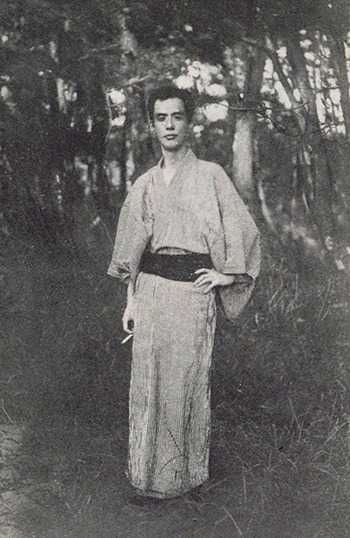

で、きょうから芥川龍之介篇であります(笑)。たまたま以前に千葉県の九十九里・一宮周辺に行ったことがあり、この芥川荘の存在を知った次第。上の芥川龍之介の写真は出典:国立国会図書館「近代日本人の肖像」 (https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/)より。

芥川龍之介という作家はまるで近代以降の日本を代表する存在。わたしも小中学校の頃に教科書でその作品に慣れ親しんだ経験がある。明治になってそれまでの分権的な封建支配体制から中央集権的体制に変わっていって、日本語自体が「統一」されるようになって、いろいろな「文豪」が輩出してくる。共通言語を作って行く過程でこういう「文化革命」があったのでしょう。そういうなかでもひとりの天才的体現者として芥川さんは登場した。

かれが東大に入学し作家活動を始めて以降、明治の気風の中で「日本言語文化草創」の中心的な存在として東大の教職にも就いていた夏目漱石は、芥川を激賞して引き立てたとされている。

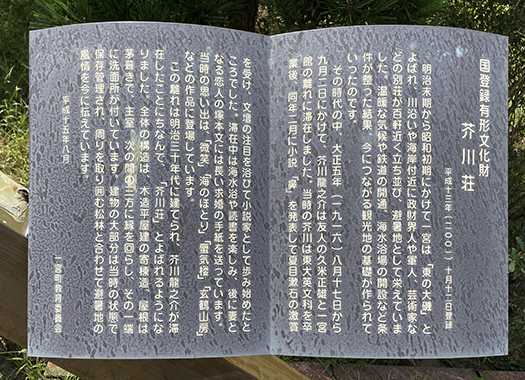

その彗星のような芥川25才の夏、かれは当時ようやく鉄道路線が東京から延伸してきて「観光地」化しはじめてきていた九十九里の一宮館の浜辺の離れに逗留して作品創作活動に明け暮れていた。そして後に夫人となる「文ちゃん」に長文のラブレターを書いたのだそうです(笑)。25才の若々しい男性の率直な恋心。写真の石碑にその状況が語られているので参照ください。

房総九十九里という、いかにも天地の生命力が感受される土地で、当時の日本文学界の期待の星であった芥川が恋文というその率直な思いを綴った庵のような空間。鴨長明が方丈記を書いたとされる「方丈の庵」のような建築と言語表現との関係を彷彿とさせるのですね。ちなみに方丈とはもともと1丈4方の建物という意味。

人と住まいの相関性の探究という意味で強い印象を受けていた次第。ということで写真もそこそこあるので、追体験的にシリーズでまとめます。いちばん上の芥川さんの写真は、その背景とか年齢の感じとか、この芥川荘での執筆当時の雰囲気とも似つかわしい。

English version⬇

Ryunosuke Akutagawa wrote a love letter to his wife at “Akutagawa-so” in Kujukuri.

To delve into the basic theme of people and their homes, a person known to everyone is an excellent subject. The space where Ryunosuke Akutagawa wrote his blatant love letters to his wife. The space for writing Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s blatant love letter.

This week, I have been going through a series of organizational changes to mark the milestone of a major change in my own environment. However, as a blog, I would like to gradually return to my usual in-depth exploration of the theme of “people and housing.

I have been covering housing for many years, so I guess my habits have become my “nature,” but my basic area of interest is the correlation between the house as architecture and its inhabitants. My interest in housing as architecture and its inhabitants is based on my memories of the experiences I have had in covering housing in the usual magazine style, and from there my interest in the way of life of the inhabitants and their way of living has deepened.

Through these experiences, I have made it my life’s work to take various opportunities to look at living spaces across the country.

So far, our main operation and activities have been as a media company, but from this change in environment, I would like to have a little more freedom to delve into this personal area of interest. Best regards.

And so, starting today, I am going to start with the Ryunosuke Akutagawa chapter (laughs). I happened to have visited the Kujukuri/Ichinomiya area in Chiba Prefecture before and learned of the existence of this Akutagawa-so. The above photo of Ryunosuke Akutagawa is from the National Diet Library’s “Portraits of Modern Japanese” (https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/).

Ryunosuke Akutagawa is one of the most famous Japanese writers of the post-modern era. I too became familiar with his works through textbooks when I was in elementary and junior high school. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), the Japanese language itself became “unified” as a result of the shift from a decentralized feudalistic system to a centralized system, and a variety of “literary giants” were produced. There must have been a “cultural revolution” in the process of creating a common language. Akutagawa emerged as the embodiment of one of these geniuses.

After Akutagawa entered the University of Tokyo and began his writing career, Natsume Soseki, who was a central figure in the “pioneering of Japanese language and culture” during the Meiji era, and who was also a teacher at the University of Tokyo, is said to have highly praised Akutagawa and praised him highly.

In the summer of that comet-like summer of Akutagawa’s 25th year, he spent all his time creating his works by staying at a remote house on the beach at Ichinomiya-kan in Kujukuri, which was then beginning to become a “tourist spot” with the extension of railroad lines from Tokyo. He wrote a long love letter to “Fumi-chan,” who later became his wife (laugh). 25-year-old young man’s frank love. Please refer to the stone monument in the photo that tells the story of the situation.

In Boso Kujukuri, a place where the life force of heaven and earth can be felt, Akutagawa, who was a promising star in the Japanese literary world at that time, wrote a love letter, a space like a hermitage where he wrote his frank thoughts. It is reminiscent of the relationship between architecture and linguistic expression, as in the “Hojo no Han” where Kamo Chomei is said to have written his Hojo Ki. Hojo, by the way, originally meant a building of one length and four sides.

In the sense of exploring the correlation between people and their homes, I had a strong impression of this building. So, since I have some photos, I will summarize them in a series as a vicarious experience. The photo of Mr. Akutagawa at the top of this page is very similar to the atmosphere of Akutagawa-so, in terms of background and age.

Posted on 10月 6th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅取材&ウラ話, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.