現代でこの一宮館は「老舗」旅館として、またこの作家との縁を強調して人気旅宿になっている。じゃらんで見てみると結構な高級旅館ぶり。九十九里の浜辺が海水浴場として鉄道も開通して、東京からの観光客が押し寄せ始めた時代、そういった一種の「ブーム」に沸いていたのかも知れない。

地図を参照してみると、この旅館の建つ位置は一宮川が九十九里にそそぐラグーンのような立地になっている。明治の大変革によって近代化の道を歩み始めた日本は、日露戦争の勝利などで「一流国」という位置を獲得し、そういう時代背景の中、大正ロマン主義のような社会の空気感があったのだろう。大衆社会化状況というような時代相が感じられる。竹久夢二のようなロマンチックな表現がもてはやされたことからは、そういう雰囲気が感じられる。

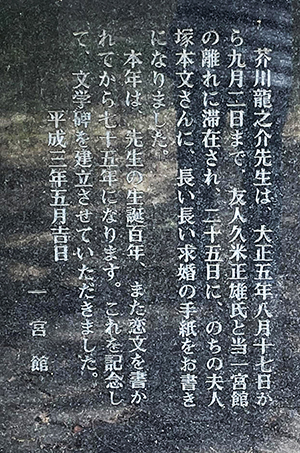

青年芥川龍之介は25才の時にこの「芥川荘」と後にかれの名声を名付けた一宮館・離れに友人・久米正雄氏と逗留した。庭園の一角に石版が置かれている。写真には大正5年の8/17〜9/2までの滞在期間が記されている。

九十九里の海浜の開放的な「真夏」感がかれの本能を激しく刺激して、かねてから恋がれていた女性のことが熱情のように脳裏を満たしていたことが想像される。その熱情がこの離れの、いかにも蒸暑地の開放的な庵という空間の雰囲気の中で涵養されたのか。まぁ、微笑ましい。いつの世でも若い男女の恋愛こそが「生きる」根源的なパワーであることは自明。

芥川の足跡を見ると、大正5(1916)年東京帝大在学中に発表した「鼻」が夏目漱石に評価され、文壇に登場とある。この旅館滞在時期とみごとに重なっている。「鼻」はこの年2月新思潮に発表されたということなので、漱石の激賞を受けて文壇各社がこの新進作家に注目し、激烈な「新刊」争奪戦が繰り広げられただろうことは想像に難くない。たぶんそのなかの1社が「夏まっ盛りの九十九里の旅館に籠もって、原稿書いてみませんか」みたいに「缶詰め」作戦に出たのかも知れない。その後の短編作品の量産ぶりを見ると蓋然性は高い。

「どうして25才の青年がこんな旅館に長期逗留できたのか?」という疑問を読者の方から提起されたけれど、背景などを考えてみるとこういった事情のように思われる。芥川は終生、この夏目漱石からの激賞に深く感謝し師弟関係を強く意識していることからも、この時期はかれが自分の未来に対して、無限の可能性を感じていたに違いない。

そういう生命力の高まりがかれをラブレターの執筆に向かわせたのだろうか(笑)。かれの多感な恋愛生活も、著名作家として個人情報などの配慮は一切なく(笑)白日の下にさらけ出されている。

江戸期の浮世絵作家、明治期の近代国家建設期の作家たちとも相違して、いわゆる大衆社会化のなかで大正期以降の作家たちは今日社会のテレビ芸能「スター」のように扱われた存在だったのだと思う。華やかな商業主義出版資本と作家の内面という点で、興味深いものがある。

やがて自死に至る「僕の将来に対する唯ぼんやりした不安」というものが、その後の日本の作家に色濃く広がっていく。なんとも言い難いものを感じてならない。

English version

Taisho Romance, Kujukuri: The Hermitage of Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Love Letter Writing – 2

Since he is a well-known writer whose writings are abundantly documented, his psychological state of mind also emerges in real time. Akutagawa’s psychological upheaval. …

Today, Ichinomiya-kan is a “long-established” ryokan and a popular inn, emphasizing its connection with the writer. A look at Jaran shows it to be a fairly high-class ryokan. The Kujukuri beach may have been in the midst of a kind of “boom” at the time when the railroad was opened as a bathing beach and tourists from Tokyo began to arrive in droves.

Referring to the map, the location of this ryokan is like a lagoon where the Ichinomiya River flows into Kujukuri. Japan began its path of modernization with the great reforms of the Meiji era (1868-1912), and with the victory in the Russo-Japanese War, the country achieved the position of a “leading nation” in Japan. This was a time of mass socialization. The popularity of romantic expressions such as those of Takehisa Yumeji suggests such an atmosphere.

At the age of 25, the young Ryunosuke Akutagawa stayed with his friend Masao Kume at Ichinomiya-kan, which he later named “Akutagawa-so” (Akutagawa Manor). A stone tablet is placed in the corner of the garden, and the third photo shows the period of his stay from August 17 to September 2, 1916.

The open “midsummer” feeling of the Kujukuri seashore stimulated his instincts, and we can imagine that his mind was filled with a passionate love for a woman he had long been in love with. Was this ardor nurtured in the atmosphere of the open hermitage space in this remote summer resort? Well, it is a very funny story. It is obvious that love between young men and women is the fundamental power of “living” in any age.

According to Akutagawa’s footsteps, he first appeared on the literary stage in 1916 when his novel “Nose,” published while still a student at Tokyo Imperial University, was highly praised by Soseki Natsume. This coincides perfectly with his stay at the ryokan. Since “Nose” was published in February of the same year in Shin-Shicho, it is not difficult to imagine the intense competition for “new publications” that ensued as the literary world paid attention to this budding writer in the wake of Soseki’s high praise. Perhaps one of the companies may have launched a “canned” strategy, asking him to stay at a Japanese inn in Kujukuri in the height of summer and write his manuscript. The fact that so many short stories have been produced since then makes it highly probable.

The reader may raise the question, “How could a 25 year old stay in such an inn for such a long period of time?” This seems to be the reason, considering the background of the story. Akutagawa was deeply grateful to Soseki Natsume for his generous encouragement, and he was very conscious of the relationship between master and disciple.

This surge of vitality may have motivated him to write the love letter (laugh). As a well-known writer, his sensitive love life is also exposed in the light of day, without any consideration for personal information (laugh).

Unlike the ukiyoe artists of the Edo period (1603-1867) and the writers of the Meiji period (1868-1912), when the modern nation was being built, the writers of the Taisho period and after were treated like the TV entertainment “stars” of today’s society in the so-called mass socialization. It is interesting to look at the glamorous commercialist publishing capital and the inner lives of writers.

The “only vague anxiety about my future” that eventually led to his suicide spread strongly among Japanese writers in the following years. I can’t help but feel something indescribable.

Posted on 10月 7th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅取材&ウラ話, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.