この家はさいたま市南区大谷口にあった安楽寺で庫裏として使用されていた住宅。建築年代としては1858年の墨書が確認されているので、165年前のもの。江戸時代の末期に建てられたけれど、その後の明治維新によって「王政復古」されたことで同時に「廃仏毀釈」の社会運動が激しく燃えさかった時代に遭遇してしまった。

一方で大谷口氷川神社の神主も兼ねていた神仏習合だったことで、非常に複雑な背景事情がこの家を襲ったことが想像される。結果として仏教寺院としての安楽寺は消滅し、この建物は庫裡である実質を失った。寺の住職としての立場は捨てたことで主人は「還俗」して野口氏に名前を変えたのだという。

わたしたち現代人にとっては第2次世界大戦での対米戦争の敗戦というのが巨大エポック民族体験だけれど、この明治の政変も社会に大きな変革をもたらしたと思う。とくにこの日本人にとってこの廃仏毀釈の宗教的大変動は大きなインパクトだった。

日本人の宗教観は歴史変動によって大きく変化してきた。縄文の世以来、自然崇拝的な信仰心は日本人の心的原風景として「八百万」の神々信仰があっただろう。そのベースに対して神武以来の王統が根付いてその正統性を証すような神社信仰が広がっていった。

そこに王統自身による仏教の導入政策があって、聖徳太子による基本的な国家体系整備が進められた。その仏教導入時にも「八百万」信仰が柔軟な社会的受容性を担保したのだろう。

戦国期には仏教勢力が石山本願寺など過激な行動主義と反権力という名の権力主義に取り憑かれていたと言えるけれど、それは政治体制としての幕府武力権力の確立とともに骨抜きされ収斂していった。江戸期の安定社会の実現までのプロセスではそうした民族体験の積層があった。

神と仏という多神教社会が実現して相互に尊重し合う社会が形成されていった。政治制度としての戦後民主主義というものもこういった日本民族の多神教受容性の一環だったとも思える。

こうした文化宗教体験の結果として日本人には同調性志向が深く根付いているのではないか。

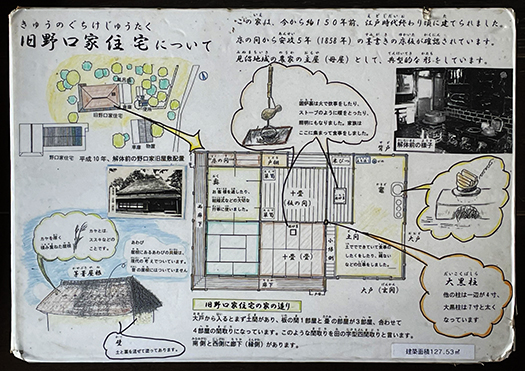

建築としてのこの家の特徴としては大きな屋根と、正面部分に掛かっている瓦屋根、せがい造りのプロポーションの端正さが強く感じられる。江戸期の寺院の庫裡では多様な集会、寄り合いなどの機会の場としてこの建物は機能していただろう。高温多湿な気候風土の中で安定的な室内環境を生み出す大きな茅葺き屋根のボリューム感、安定感は民族的心性の揺りかごになったように思える。

こうした大きな茅葺き屋根の美感からは日本社会の安定、ひとびとの倫理感の揺りかごのような印象が強く感じられる。

English version⬇

Neat form and a sense of shading: Hikawa Shrine’s Yuhiken Shrine and Anraku-ji Temple’s Kori -2

The thatched roof and the aesthetic sense of the segai-zukuri style create a Japanese-style orientation toward a sympathetic society. It makes us feel the fundamental sense of ethics. ・・・・・・.

This house was used as a korori (storehouse) at Anrakuji Temple in Oyaguchi, Minami-ku, Saitama City. As for the building date, the ink signature of 1858 has been confirmed, so it is 165 years old. It was built at the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), but it was destroyed by the “restoration of the monarchy” during the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), which was followed by the social movement to “abolish Buddhism” that flared up violently.

The family was also the head priest of the Oyaguchi Hikawa Shrine, which was a syncretism of Shinto and Buddhist teachings, and one can imagine that the background of the family was very complicated. As a result, Anrakuji Temple as a Buddhist temple ceased to exist, and this building lost the substance of being a koryu. The owner, having abandoned his position as the temple’s abbot, “returned to the priesthood” and changed his name to Mr. Noguchi.

For us modern people, the defeat in World War II against the U.S. is a huge epochal national experience, but I believe that the political upheaval of the Meiji period also brought about a great change in society. Especially for the Japanese, the religious upheaval caused by the abolition of Buddhism had a great impact.

The Japanese view of religion has changed greatly due to historical changes. Since the Jomon period, nature-worshipping belief in the “eight million” gods has been a part of the Japanese people’s spiritual landscape. The royal lineage since the Jinmu period took root against this base, and shrine worship spread as a testimony to its legitimacy.

The royal lineage itself introduced Buddhism, and Prince Shotoku promoted the development of a basic national system. The belief in “eight million” probably ensured flexible social acceptability at the time of the introduction of Buddhism.

During the Warring States period, Buddhist forces such as Ishiyama Honganji were obsessed with radical activism and anti-authoritarianism, but these were suppressed and converged with the establishment of the Shogunate’s military power as a political system. In the process of achieving a stable society during the Edo period, there was a layering of such ethnic experiences.

A polytheistic society of gods and Buddha was realized and a society of mutual respect was formed. Postwar democracy as a political system seems to have been a part of this acceptance of polytheism among the Japanese people.

As a result of these cultural and religious experiences, a syncretic orientation may be deeply rooted in the Japanese people.

The house is characterized by its large roof, the tiled roof over the front portion, and the neat proportions of the segai-zukuri style. This building would have functioned as a place for various meetings and gatherings in the koryu of temples during the Edo period. The volume and stability of the large thatched roof, which creates a stable indoor environment in the hot and humid climate, seems to have served as a cradle for the spirituality of the people.

The aesthetics of these large thatched roofs give a strong impression of the stability of Japanese society and the cradle of people’s sense of ethics.

Posted on 7月 28th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.