本日も徳島県の山間の「空中住居」とでもいえる三木家住宅その2であります。

わたしたち現代人は利便性最優先で経済的根拠に基づいて住宅を建てたり、購入する場所を選んでいる。これが支配的で多くの場合、職場との時間距離と見合うかで判断して居住地を決定するケースが多いのだと思う。

一方でそれとは違って先祖代々その土地に住み続けて、そうすることが自然だと考えて住んでいるというケースもあるだろう。日本社会の構造としての食糧生産システム、農村社会のありようがそれに相当する。前者が現代的経済効率に根拠を置くのに対して、こちらは伝統的な経済共同体の価値感を重視する考え方と言えるのだろう。日本的ムラ社会もまた過去から経済基盤最優先の居住選択だろう。山岳地域での棚田主力では「水利」の面で困難が伴うので、その多くは水利を第1に考えた立地環境、多くは河川流域を開発した地域に立地する。

この徳島県の山岳高地に点在居住する共同体の中核的古民家を見ていると、どうもそういった常識的価値感とは違った生き様を見る思いがしてくる。いわば現代生活とも伝統的農業ムラ共同体社会とも違う、古代的なスピリチュアルな価値感、といったものを感じさせられていた。

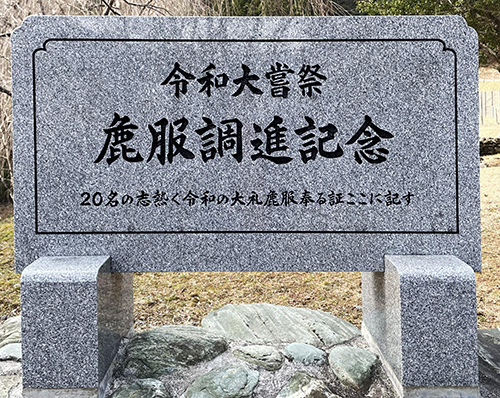

上の写真はこの三木家住宅の「麻畑」とおぼしき畑地と令和の麁服(あらたえ)調進を成し遂げた記念碑。畑地は整然と区画されて入口には鳥居まで建てられている。この内部で朝廷に調進される麻が育成されていたと推定できる。訪問時にはシカの糞が随所で散見された。そういう光景も自然な施肥のように思えて意味ありげと思われる。自然環境と共生することが「神宿る」ことの実質と感じられるのだ。こうした高地をあえて居住地として選択する意思には、忌部氏という部民としての古代的価値感があるのだろう。「神がかり」ということが上位価値感であるという意思がこの地では現代まで一定の存続を果たしてきている。その奇跡性。

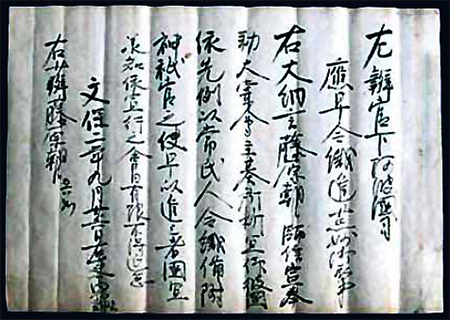

そういう奇跡性を表すようにこの三木家には鎌倉から室町にかけての古文書「三木家文書」が残されている。写真は文保2(1318)年の後醍醐天皇の大嘗会(天皇践祚)時点でのもので、上の方は勅使が神部2人を連れて阿波国に下向する旨を国司に申し渡した文書。下は官宣旨という「下文」とされ、先例に倣って麁服(あらたえ)を織らせるようにという申し渡しの内容。

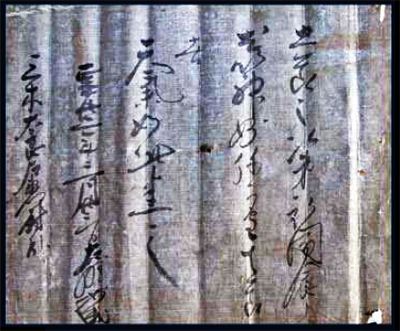

さらには南北朝の時代、正平22(1368)年という南朝で使われた元号年で表された三木家当主・重村に宛てられた「感状」の綸旨。鎌倉時代末には三木家は南朝に忠誠を尽くした地域武士団の棟梁であったという。脈々と古代的価値感が根付いていることに驚く。四国の山深い地域、現代ではほとんど限界集落と思える地域で、こういう「神宿る」価値感が残り続けていることは、ある種、民俗の底深さを教えてくれる。

日本という国家社会にはまちがいなくこういう山上での空中生活を「神との共生」として尊崇するスピリチュアルな部分が根底にあるのだと思う。アイヌの人びとの伝統的価値感とも通底するような、歴史以前社会から連綿と伝わる民族性の実質なのだろう。先般見た高鴨神社のように弥生以前をも感じさせる。

現代社会はこういう神々しさをどのように未来へ手渡していけるのだろうか?

English version⬇

Commitment to a mountain highland lifestyle where the gods reside MIKI Residence, Tokushima – 2

Ancient “kamikari” life on the mountain, which is different from the rural village community. The spiritual values of this lifestyle remind us of the roots of folklore. Tokushima, Japan

Today, we continue our look at the Miki Family Residence #2, an “aerial dwelling” in the mountains of Tokushima Prefecture.

We modern people choose where to build or buy a house based on economic rationale, placing the highest priority on convenience. In many cases, this is the dominant factor, and in many cases, people decide where to live based on the distance from their workplace in time.

On the other hand, there may be other cases where people have lived in the same place for generations, and they live there because they think it is natural to do so. The food production system as a structure of Japanese society and the way rural society is organized correspond to these cases. While the former is based on modern economic efficiency, the latter emphasizes the values of a traditional economic community. The Japanese “mura” society has also placed the highest priority on economic infrastructure in its choice of settlement. Since terraced rice paddies in mountainous areas are difficult to manage in terms of “water use,” most of them are located in areas where water use is the primary consideration, often in developed river basins.

Looking at these old private houses, which are the core of the community living scattered in the mountainous highlands of Tokushima Prefecture, one gets the impression of a way of life that differs from such common sense values. I felt a sense of ancient spiritual values that are different from those of modern life and traditional farming communities.

The photo above shows what appears to be the “hemp field” of the Miki family residence and the monument that commemorates the completion of the “araatae” ceremony in 2025. The field is neatly divided into sections, and even a torii gate has been erected at the entrance. It can be presumed that hemp to be supplied to the Imperial Court was cultivated in this area. When we visited, deer droppings were found everywhere. Such a sight seemed to be a natural way of fertilization and meaningful. It seems to me that living in harmony with the natural environment is the essence of “dwelling with the gods. The intention to choose such highlands as a place to live may be due to the ancient sense of value of the aborigines as a tribe. The will that “kami hakari” is a higher value has survived to the present day in this area. The miraculousness of it.

As if to show such miraculousness, the Miki family has left behind an old document, the Miki Family Document, dating from Kamakura to Muromachi period. The upper one is a document in which an imperial envoy sent a notice to the provincial governor that he was going down to Awa province with two Shinto priests. The lower part is said to be a “letter of condolence” called “kansenjinshin,” in which the imperial envoy instructed the provincial governor to have them weave clothes in accordance with the precedent.

Furthermore, in the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the “Kanjou” (impressed letter) addressed to Shigemura, the head of the Miki family, expressed in the year Shohei 22 (1368), the original year used by the Southern Dynasties. By the end of the Kamakura period, the Miki family was the leader of a local warrior clan loyal to the Southern Court. It is surprising that ancient values have taken root in the area from generation to generation. The fact that such a sense of “kami shuku” (the gods reside in the land) continues to exist in a mountainous region of Shikoku, an area that today seems almost a marginal settlement, tells us something about the depths of folklore.

I have no doubt that Japan’s national society has a spiritual basis in its reverence for this kind of aerial life on the mountains as “coexistence with the gods. This is the essence of the ethnicity that has been handed down from pre-historic society, which is also the same as the traditional values of the Ainu people. Like the Takagamo Shrine I saw the other day, it also reminds us of the Yayoi period.

How can modern society pass on this kind of godliness to the future?

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.