この関根家の家族のための日常、ケの空間。

土間とつながる作業動線をもつダイドコ、外には井戸があって

炊事洗濯に必要な用水が確保されている。

カイコの世話のための2階への動線起点のアガリハナは一体型の板の間であり、

神棚のあるウラザシキには掘り炬燵型のテーブル。

神棚の下に中空の棚状空間があり、やや小さめだが仏壇の位置なのか。

そうだとすれば、神仏先祖たちと日々の暮らしに感謝する様子が

みえてくる光景かも知れない。

「仏さんに手を合わせてからご飯だよ」

と言われて拝礼し、ついでに神さまにもあいさつして炬燵に潜り込んで

テーブル上の食事に向かっていた様子が目に浮かんでくる。

「いただきま〜す」

土間まで開放された空間で、日々の労働からいっとき解放時間をすごす。

で、こういう「家族だけのための空間」っていうのは

この大きな関根家住宅全体の中ではごく小さな面積。

土間は本質的に農作業の場であり、この養蚕の家では板敷きの間も、

カイコのために使われることも多かったとされる。

2階は常時カイコと製糸生業のための空間。

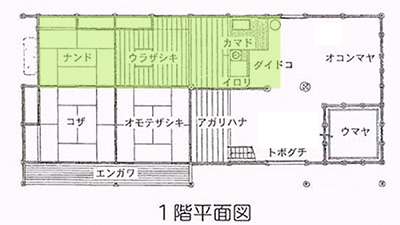

プライベートゾーンは主に家族寝室である畳敷きのナンド6畳(押入付き)

ウラザシキ8畳、ダイドコおおむね8畳ということになる。

全部で押入も算入しても24畳、なので12坪ほどに集約される。

この空間面積でふつうは8人程度の家族全員が集っていた。

その他のオモテ座敷・コザなどはハレの場であって半ば公共的空間だった。

質素倹約に勤めながら、つねに公的な用途に備えて家を維持する、

そんな日本人のDNA的な家屋意識というものが浮かび上がってくる。

この公共への対応力、家の「奥行き」が家格を表現していた。

武家に至っては「滅私奉公」という生き方が本旨とされた。

庶民はそこまでではないが、それでも公共への帰依は存在した。

明治になって世界との対話がはじまったとき

素朴な人間欲求と個人主義価値感に基づく「経済社会」と遭遇したとき、

こういう日本社会の価値感は揺らいだに違いない。

しかし明治のスタートから第2次大戦直前までで人口規模は

約3,000万人から8,000万人ほどまで増加し、経済規模も拡大した。

欧米世界標準を受け入れることで近代国家としての成功を成し遂げた。

さてそれから戦後を迎えて以降、この世界標準的ライフスタイルは

普遍的に日本の家屋のありようを変えていっている。

葬式や法事会合などは専用施設に役割移転し、

親族でも相手の家に宿泊するという習慣は大きく廃れた。

近隣のホテル宿泊などでプライバシーへの気遣い不要に変化した。

そういう「公的交流」の場が家から失われて、

家族だけの空間が住宅のもっとも肝要な目的に変化してきている。

かつての「公共空間」のような役割空間が家から消えた後、

さて、わたしたち現代日本人はどんな意味のある空間を欲するのだろうか。

そういえばコンパクトとか、平屋という志向性は強まっている。

民家のミライが非常に興味深い・・・。

English version⬇

Japanese DNA family-only zone “Akagi-style” silkworm farm house-7

The house is about 12 tsubo in area, which is enough for a family to live together. The family strived to be thrifty and respected public space. The public sitting room space has disappeared in the modern age, but now….

Daily life for this Sekine family, ke space for the family.

The daidocho has a work flow line that connects to the earthen floor, and there is a well outside to

Outside, there is a well that provides water for cooking and washing.

Agarihana, the starting point of the flow line to the second floor for taking care of the silkworms, is an integrated board room.

The urazashiki, which houses a Shinto altar, has a kotatsu-type table.

There is a hollow shelf-like space under the altar, which is rather small, but is it the location of a Buddhist altar?

If so, it may be a scene of gratitude to the gods, Buddha, ancestors, and daily life.

If so, it may be a scene of gratitude to the gods, Buddha, ancestors, and daily life.

After praying to the Buddha, we eat our meals.

Then, after greeting the gods, I got under the kotatsu (table-top table) and went to the table to eat.

I can just picture the way they were eating their meals on the table.

Itadakimasu!

In the space that is open to the earthen floor, we spend a moment freeing ourselves from the daily labor.

This kind of “space just for the family” is a part of the whole Sekine family’s house.

This “space just for the family” is a very small area of the entire Sekine family’s large residence.

The earthen floor is essentially a place for farm work, and in this sericultural house, the wooden floor was often used for silkworms.

The second floor was always used for silkworms and silkworms.

The second floor is always a space for silkworms and the silk production industry.

The private zone consists mainly of the family bedroom, 6 tatami-mat nando (with a closet), 8 tatami-mat urazashiki

The private zone was mainly used as a family bedroom: 6 tatami mats for Nando (with a closet), 8 tatami mats for Urazashiki, and roughly 8 tatami mats for Daido.

The total space is 24 tatami mats, including the oshirooms, which means that the total space is about 12 tsubo.

Usually, a family of about 8 people would gather in this space.

The other areas, such as the omote-zashiki and koza-zashiki, were the “hare (formal occasions)” and were half-public spaces.

While striving to be frugal and thrifty, the Japanese always maintained their houses for public use.

This is the DNA of the Japanese sense of the house.

This ability to respond to public needs and the “depth” of the house expressed the family’s status.

The samurai family was expected to live a life of “selflessness and devotion.

Although the common people were not to that extent, they still had a devotion to the public.

When dialogue with the world began in the Meiji era

When they encountered an “economic society” based on simple human desires and individualistic values, the values of Japanese society were shaken.

These values of Japanese society must have been shaken.

However, from the start of the Meiji era to just before World War II, the size of the population

However, from the start of the Meiji period to just before World War II, the population grew from about 30 million to about 80 million, and the economy expanded as well.

By embracing Western world standards, Japan achieved success as a modern nation.

Since then, after the postwar period, this world-standard lifestyle has been universally changing the way Japanese houses are built.

Since the postwar period, this world-standard lifestyle has been universally changing the way Japanese houses are built.

Funerals and memorial services have been relocated to dedicated facilities, and the custom of staying with relatives in the other’s home has largely disappeared.

The custom of staying at the other party’s house, even for relatives, has largely disappeared.

The custom of staying at a nearby hotel has changed so that people no longer need to worry about privacy.

The place for such “public exchanges” has been lost from the home.

The most important purpose of a house is to provide a space for the family to live together.

Now, we modern Japanese are wondering what kind of role space, like the “public space” of the past, we will be able to play after the disappearance of such space.

What kind of meaningful space will we modern Japanese desire after the role of “public space” disappears from our homes?

The trend toward compactness and one-story houses is increasing.

The minka future is very interesting…

Posted on 8月 24th, 2022 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.