明日香や奈良地方を巡っていると古墳の多さに驚くのだけれど、

それは印象論で実は古墳の多さでは兵庫県が一番だと言われています。

〜國學院大學メディア「ゼロから学んでおきたい「古墳」③」より抜粋。

<●古墳の数 文化庁埋蔵文化財関係統計資料の「周知の埋蔵文化財包蔵地数」

(平成28年度版)によると、全国には15万9623基の古墳・横穴が確認される。

都道府県別では、①兵庫県1万8851基②鳥取県1万3486基③京都府1万3016基

④千葉県1万2765基⑤岡山県1万1810基-となっている。

一方、北海道、青森県、沖縄県には古墳・横穴が確認されていない。>

ただし兵庫県などは6~7世紀の「群集墳」爆発的増加期のものが多いとされ、

この群集墳は小型で一族連鎖的な葬送方法とされ、それまでの古墳被葬者とは

階層自体が大きく違っているとされていました。

やはり、大型で「一世一代」的な建造物である古墳の分布としては実質的に

奈良盆地地方は多いのだろうと思います。

この「一世一代」というコトバは日本の王権古墳文化を象徴するかも。

個人に対するリスペクト表現として古墳「建築物」が作られた。

その基本は「土葬」という日本国土在来的な死生観なのでしょう。

きのう触れたようにそういう時代から仏教の伝来拡散を迎えて

釈迦牟尼自身も葬送されたという「火葬」風習が日本に伝来した。

天武帝の皇后であった持統帝は火葬された上で旦那さんの天武帝のために作った

古墳に自らのお骨も随伴させて葬らせたという。

この飛鳥京最後のふたりの天皇は日本社会の変化を象徴している。

日本人の死生観の変化がこの飛鳥京の最期の時期にスタートした。

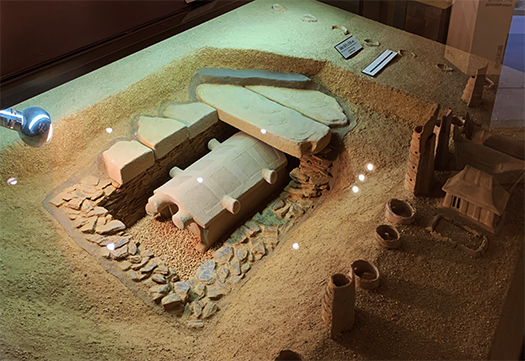

写真の3番目は宮廷官人であった太安万侶の「火葬墓」のモデル展示。

橿原考古博物館での展示ですが、この墓からはかれの「墓誌」も納められた。

今日われわれの墓石の付随物としての墓誌の初源かと。

この死生観を巡っての日本社会の有為転変はその後ながく続いてきた。

江戸期には広範に火葬が広がっていたけれど、明治維新で神道翼賛体制で

一時期火葬を禁止するという政令も出されたけれど2年程で撤回された。

それは深刻な「土地問題」に起因していたということです。

やはり土葬では国土の狭い日本社会では早晩破綻する。

たぶん日本社会では土地利用と葬送方法の二律背反が常に生起したと思う。

ただ死んだあとの葬送というのは直接その人の「生き方」にも深く関わる。

古墳という形態で送られた先人たちの魂魄、その思いというものも

はるかな後世のわれわれは、その「精神性」をしっかり受け止めていきたい。

つながっていることを重視したいと思うところです。

English version⬇

Japanese View of Life and Death “Burial and Cremation” Exploration of Asuka, Nara – 13

The burial after death is deeply related to the “way of life. The souls of our predecessors are described in this way. As Japanese, we should take it seriously. …….

When you visit Asuka and Nara area, you may be surprised at the number of ancient tombs, but that is just an impression.

But this is just an impression, and in fact, Hyogo Prefecture is said to have the largest number of kofun tumuli.

〜The following is an excerpt from the Kokugakuin University media article, “Kofun Tumuli: What You Need to Learn from Zero (3)”.

<According to the “Number of well-known burial sites of cultural properties” (2008 edition) of the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ statistical data related to buried cultural properties, Hyogo Prefecture has the largest number of kofun tumuli.

(According to the “Number of Kofun Tumuli” (FY 2008 edition), 159,623 kofun tumuli and yokoana (burial mounds) have been confirmed throughout Japan.

By prefecture, (1) Hyogo Prefecture 18,851 tombs, (2) Tottori Prefecture 13,486 tombs, (3) Kyoto Prefecture 13,016 tombs

(4) Chiba Prefecture: 12,765 (5) Okayama Prefecture: 11,810

On the other hand, no burial mounds or horizontal holes have been confirmed in Hokkaido, Aomori, or Okinawa Prefectures. >(6) Hyogo Pref.

However, many of the burial mounds in Hyogo and other prefectures are said to date from the 6th and 7th centuries, when the number of “cluster burial mounds” exploded.

These cluster burial mounds were small and were considered to be a family-oriented burial method, and the hierarchy itself was considered to be very different from that of burial mound burials up to that time.

The hierarchy itself was considered to be very different from that of the burials in earlier burial mounds.

The distribution of kofun tumuli, which are large, “once in a generation” structures, is substantially larger in the Nara Basin region than in other regions of Japan.

I think that the distribution of kofun tumuli, which are large, “once-in-a-generation” structures, is substantially greater in the Nara Basin region.

The phrase “Issei-ichi” may have origins related to ancient tombs.

Kofun “buildings” were created as an expression of respect for the individual.

The basis for this is probably the traditional Japanese view of life and death, “burial in the ground.

As I mentioned yesterday, the spread of Buddhism from such a time period led to the establishment of the burial mound.

The custom of “cremation,” in which Shakyamuni himself was buried, was introduced to Japan.

Emperor Mochito, who was the empress of Emperor Temmu, was cremated and her own bones were buried in a burial mound that she had built for her husband, Emperor Temmu.

Emperor Mochito, who was the Empress of Emperor Temmu, had her own bones buried in a burial mound that she had built for her husband, Emperor Temmu.

The last two emperors of Asuka-kyo symbolize the changes in Japanese society.

The change in the Japanese view of life and death began during the final days of Asuka-kyo.

The third photo is a model exhibit of the “cremation tomb” of Taian Wanpo, a court official.

The third photo shows a model of the “cremation tomb” of Taian Manpo, a court official.

This may be the origin of the epitaph that accompanies our gravestones today.

The changes in Japanese society regarding this view of life and death continued for a long time.

During the Edo period (1603-1867), cremation was widely practiced in Japan, but the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) led to the Shintoist movement to ban cremation for a period of time.

A decree banning cremation was issued for a period of time, but was withdrawn after about two years.

This was due to a serious “land problem.

After all, burial in the ground would soon fail in the narrow land area of Japan.

Perhaps the dichotomy between land use and burial methods has always existed in Japanese society.

However, after death, burial is also deeply related to a person’s “way of life.

The souls of our predecessors who were sent in the form of burial mounds, and their thoughts and feelings

We, the future generations, would like to take in the “spirituality” of our ancestors.

I would like to emphasize the importance of the connection between the two.

Posted on 4月 28th, 2022 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.