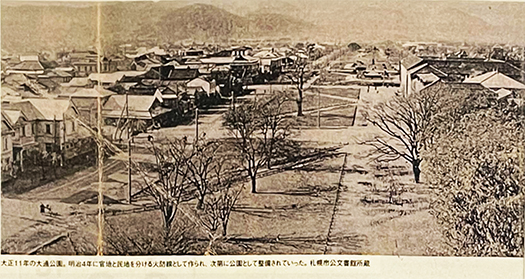

この有島武郎旧邸が新築された当時の札幌の人口は大正2(1913)年段階で総数96,897人で男性52,867、女性44,030。現代の約1/20程度。現在の札幌市内22年新設住宅着工は15,761戸。さすがにこの大正期の着工数は資料が少ないようだけれど、単純に1/20と考えて見ると7-800戸程度が類推される。

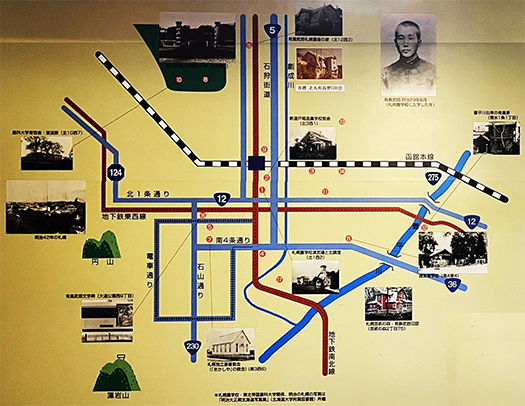

けっこうな数の住宅が建てられていることになる。わたしの一家が札幌に移住してきたのは今から68年前。この当時、北3条西11丁目の角地で「木下藤吉」という不動産屋が建てていた「建売住宅」を購入したと聞いている。人口集中が進んでいた札幌市内では、100年前のこの有島自邸建築の当時でも活発な不動産業者、建設業者の活動があったことだろう。

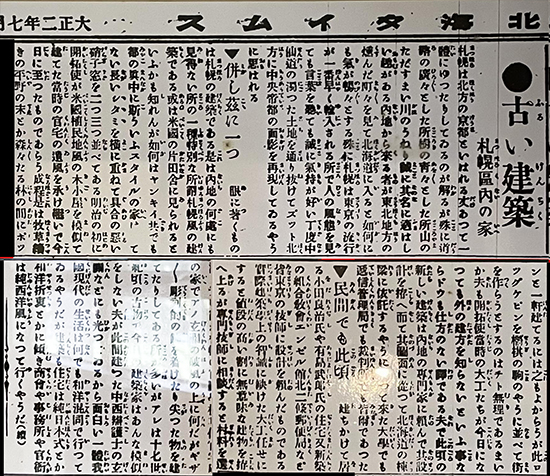

間に太平洋戦争は挟むことになるけれど、高々30数年の時間しかないことになる。札幌の住宅の流れには一定の歴史把握も進められていて「ハイカラ」な戸建て住宅の羨望の対象として、大学教授による新築住宅が話題にはなっていたとされている。

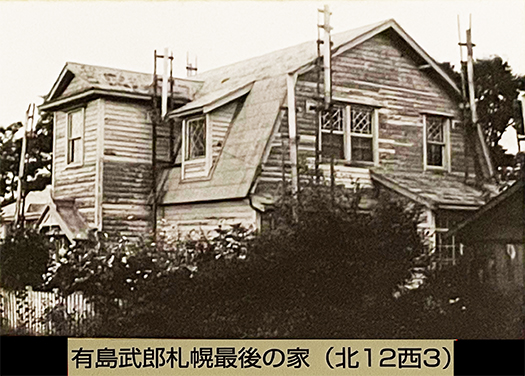

その嚆矢に近く、そういう評価・評判を高めたのがこの有島旧邸と言える。その他にも開拓使や道の高官が建てた家も話題にはなっていたとされる。そういった住宅建築についての独特の地域的情報の共有性・土壌がこうした有島さんなどの活動の結果としてあるのだろう。地域をリードする学問の中核的人材として、そういった自覚もあったことだろう。地域の住宅雑誌という人生行路を体験してきて刮目させられる瞬間。

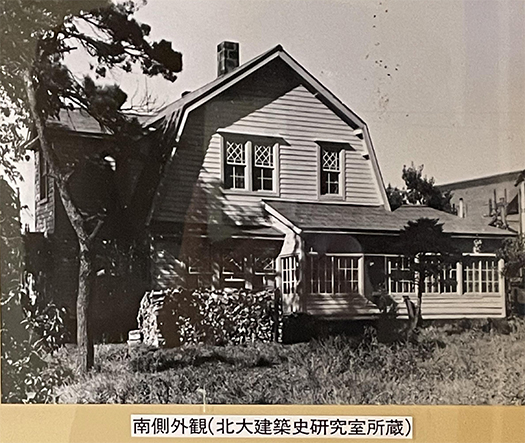

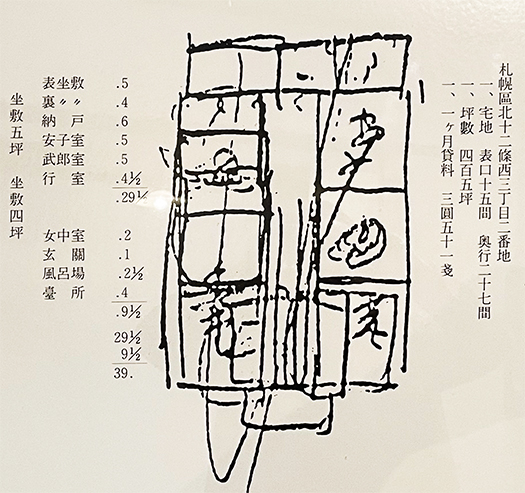

上の有島自身による手書きスケッチは旧邸に置かれていた展示より複写。

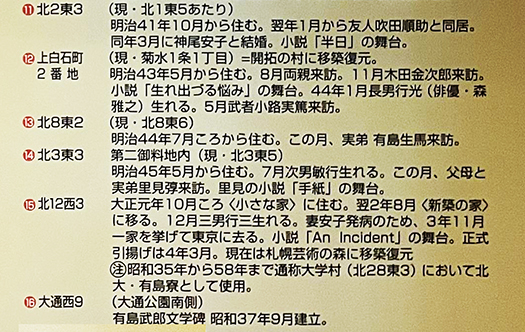

土地は405坪で借地だったようだ。1ヶ月賃料で3円51銭とある。2019年と比べると、1,080倍の差があるというWEBでの一般的な説に従うと、1ヶ月4,000円程度となるけれどさてどうか。

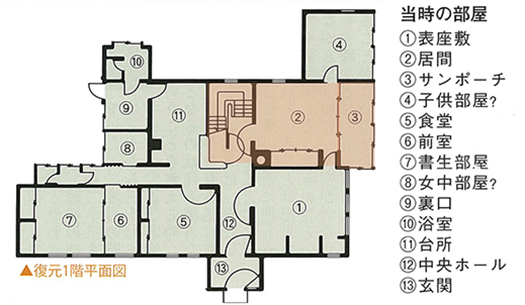

住宅の「間取り」の考え方として「坐敷五坪」などという単位が書かれている。その他の諸室についてもたぶん坪数表記で配分が示されているように思われる。写真は上が「台所」と想定できる部屋と、洋間が展開している2階の様子。大学教官として自室が必須だったことから奥さんと子どもたちのための個室も造作されていったのだろうか。

家族の為の部屋、奥さんと生まれたばかりの赤ちゃんも含めた3人の子どもたちが暮らす部屋は居間に隣接する1階の個室が想定される。居間と一体化し、サンポーチも付設された空間が有島家の一家団欒の場だったのだろうか。

有島自身のための個室は台所の向かい側の個室か、あるいは2階に造作されていたことが想像されてくる。また時代を反映して「女中部屋」というのも2坪ほどの部屋が用意されている。広大な住宅の維持管理のためには産後間もない奥さんでは手が回らなかっただろうことが考えられる。

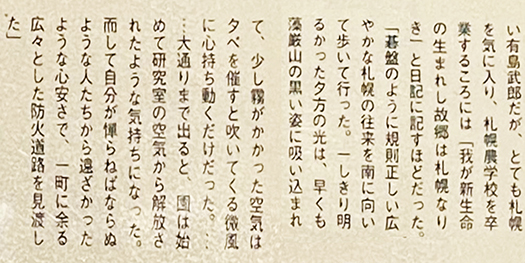

そして奥さんが肺結核を患ってしまって、幼子3人を抱えての札幌での生活が維持できなくなって、この家での家族だけでの暮らしを諦めざるを得なくなっていく。家は家族のドラマを反映し残像をみせてくれる。

English version⬇

Sketch of the builder’s own design plan of the former residence of Takeo Arishima-7

The plan drawings reveal in detail the state of the Arishima family at that time. It shows the joys, sorrows, and the way of life of the Arishima family. The house was built in the late 1960’s…

When the former residence of Takeo Arishima was built, Sapporo had a total population of 96,897 in 1913, of which 52,867 were males and 44,030 were females, about 1/20 of the present population. The current number of new housing starts in Sapporo in 2010 is 15,761. Although data on the number of housing starts during the Taisho period are scarce, a simple 1/20 estimate suggests 7,000 to 8,000 housing units.

This means that a considerable number of houses were built in the Taisho period. My family moved to Sapporo 68 years ago. At that time, I heard that they bought a ready-built house on a corner lot in Kita 3-jo Nishi 11-chome, which was built by a real estate agent named “Fujikichi Kinoshita. In Sapporo, where the population was concentrated, there must have been active real estate agents and builders even at the time of construction of Arishima’s own residence 100 years ago.

Although the Pacific War intervened between the two periods, it was only 30 years or so at most. There is a certain amount of historical understanding of the housing trend in Sapporo, and it is said that newly built houses by university professors were the object of envy for the “high-colored” detached houses.

The pioneer of this trend was the old Arishima Residence, which gained a high reputation and recognition. Other houses built by high-ranking officials of the Kaitakushi (Hokkaido Development Office) and Michi (Hokkaido Prefectural Government) are also said to have been the talk of the town. The unique regional character and soil of residential architecture may be the result of the activities of Mr. Arishima and others. Having experienced the life path of a local housing magazine, there are moments when I look back on it.

The hand-drawn sketch above is from an exhibit at the Arishima residence.

The land is 405 tsubo (3,860 m2) and was leased, with a monthly rent of 3.51 yen, which, according to a popular theory on the web, is 1,080 times higher than in 2019, or about 4,000 yen per month, but we will see.

It is imagined that Arishima himself had a private room either across from the kitchen or on the second floor. Reflecting the era, a “maid’s room” of about 2 tsubo (3.5 square meters) is also provided. It is thought that the wife, who had just given birth, would not have been able to handle the upkeep and maintenance of the spacious house.

Then the wife contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and was unable to sustain life in Sapporo with three young children, forcing the family to give up living alone in this house. The house reflects the family drama and shows us afterimages.

Posted on 10月 22nd, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング | No Comments »