わたしは筆跡についての知識はありませんが、自分のヘタな字面を毎日のように見ていると、そこに自分のダメさ加減が如実に表れていると自責させられている。たぶん多くの人が、自分の書いた文字について密かな自問自答を繰り返しているのだろうと思います。そういう自分にしてみると、世界がパソコンに一変してきたことは、潜在的で根深い劣等感からのひそかな「解放」にもなっている。

でも、それは人間と文字文化についてのきわめて根源的な「革命」であって、あとで「人類が喪失した重要な手業の痕跡」ということに認定されてしまう可能性もある。

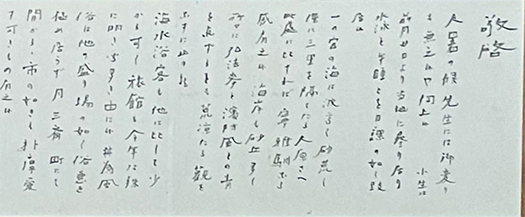

芥川さんの上のハガキ文字の書きようからは「あ、けっこう投げやりっぽい」という印象も持たされる。特に「込」の左側、しんにょうが一筆書きになっているあたり「ま、これで通用するだろう」みたいな芥川さんの個性とか、内語の発露というように感じられる。

草書、行書、楷書みたいな書き方分類からすれば、ハガキなどは草書の最たるものだろうから、こういった心理で書いていくときにはその心理の雰囲気伝達も含めて蓋然性があるのでしょう。

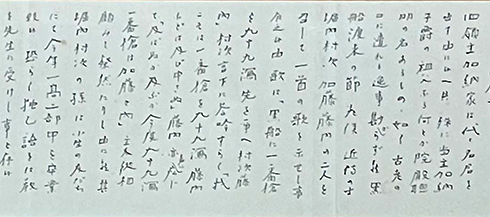

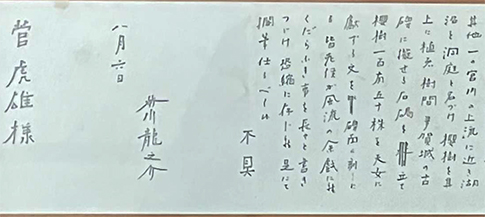

一方で、きちんとした手紙文章については、楷書とまでは言わないけれど、一字一字、丁寧な筆遣いで「克明」感がある。「敬啓」という文頭熟語はイマドキのPC辞書には発見できない。たぶん「敬って」「申し上げます」みたいな内意を表現したと推測できるが、芥川の存命当時はまだ日本語共通語が完全には成立していない時期だと思えるので、かれ芥川としては気に入った文頭語として独自に創始したのだろうか。

あるいはもっと進んで、恩師・夏目漱石たちが必死に取り組んでいた近代日本の文化基盤としての共通語創造作業に対して、リスペクトしつつ芥川オリジナルな文章表現を社会に提案していたのかも知れない。東京帝大文学部学生としての国家的役割の自覚、明治末・大正初期の国語文化創造の民族的使命感の一端がそこに示されてもいるようだ。

先般来見て来ている「恋文」についてはこのような肉筆は公開されていない。恋情という生々しい心情吐露において、その書き方が行書だったか、草書だったかは、非常に興味深い。恥ずかしながら自分事として思い返してみても、そのあたりは明晰ではない。また追確認する術もほぼない(笑)。コピー装置のない時代、一期一会としての書き文字にはそういう「気迫」のようなものも託されていた。

司馬遼太郎の作品に「街道をゆく」があり、そのなかの本郷界隈篇では夏目漱石らの明治国家初期の文化創出期の人間像、その苦悩ぶりなども表現されているけれど、その直系ともいえる芥川にも日本共通語創出期の熱気を感じさせられる。

English version⬇

Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Hermitage in Kujukuri – 8] Touching the Writings of the Great Writers

Akutagawa and his contemporaries must have been in the reverberations of Soseki Natsume’s generation, who created the lingua franca of Japan. We will explore their psychology in cursive and running script. …

I am not knowledgeable about handwriting, but when I look at my bad handwriting on a daily basis, I am reminded that my ineptitude is truly expressed in it. I think many people probably repeat the secret self-questioning about their own writing. For such a person as myself, the fact that the world has been transformed by personal computers has been a secret “liberation” from a latent and deep-seated sense of inferiority.

But it is also a very fundamental “revolution” about human beings and writing culture, which could later be qualified as “a trace of an important handiwork that humanity has lost.

The way Akutagawa writes the postcard characters above also gives the impression of “Oh, it looks quite throwaway. In particular, the single stroke on the left side of “kome” (込) and “shinyou” (しんにょう) give the impression of Akutagawa’s individuality and the expression of his internal language, as if to say, “Well, this will work.

In terms of writing styles, such as cursive, running script, and standard script, postcards are probably the most common type of cursive writing.

On the other hand, as for the proper writing of a letter, each character is carefully handwritten and has a sense of “conquering”, although it is not necessarily in block style. The phrase “Dear Sir/Madam,” which is an idiom at the beginning of a sentence, cannot be found in modern PC dictionaries. It is assumed that it was used to express the meaning of “respectfully” or “respectfully,” but since the common Japanese language had not yet been fully established at the time of Akutagawa’s death, he may have created his own favorite idiomatic expression.

Perhaps Akutagawa was respecting the efforts of his mentor Soseki Natsume and others to create a lingua franca as the cultural foundation of modern Japan, and at the same time, he was proposing his own original writing style to society. This may have been part of Akutagawa’s sense of national mission to create a national language culture at the end of the Meiji and early Taisho eras.

As for the “love letters” that we have been looking at for some time now, no such writings have been made public. It is very interesting to know whether the writing style was cursive or cursive, as it is a very vivid expression of the feelings of love. I am ashamed to admit that when I think back on it as a matter of personal experience, I am not quite clear on this point. I am ashamed to admit that when I think back on my own life, I am not so clear about it, and there is almost no way to check. In an era without photocopying equipment, the written word, which was a once-in-a-lifetime event, was entrusted with a kind of “spirit” as well.

Ryotaro Shiba wrote “Kaido yuku” (“On the Road”), in which he describes the human image of Soseki Natsume and others during the period of cultural creation in the early Meiji era, and the anguish they endured.

Posted on 10月 13th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.