芥川龍之介の九十九里での一時滞在の和風庵からの延長線的流れで、「作家の住まい」的な興味深化からこの有島武郎の札幌に残る住宅を分析してみることにしたのですが、掘り下げるほどに北海道の住宅進化の過程と驚くほどに重ね合わさって、作家の・・・という興味を超えて、北海道住宅のデザイン史の始原とも思えてきた。

わたしという人間は「北海道でメディア、それもリッチコンテンツなものを」という思いからもっとも北海道らしいテーマとして住宅という領域を選択したのですが、「おまえ、そういう選択をしたのだから、突き詰めてテーマを追求しろよ」とはるかな偉人・有島さんから叱咤されているように感じられる(笑)。

そういうように思えるというのは、たいへんシアワセなのではないかと思っております。

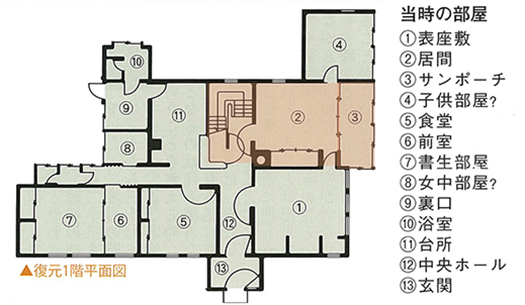

ということで本日は図面の中で不思議さを感じていた「サンポーチ」であります。110年前なのでいかに英語教授である有島武郎にしても、サンルームという現代的一般空間名称には認識が至らなかったのか、いやそうではなく、日本人的な感覚として「縁側」の西洋住宅類型としてむしろこういう語感がふさわしいと感じたのか,ナゾ。

写真ではイマイチ鮮明ではありませんが、この区域の窓だけは、ほかの居室の窓のように「上げ下げ窓」ではなく、引き違いの窓・建具が使用されている。ガラスも他の部屋ではデザイン造形された枠が施されているけれど、この区画だけはガラス素地になっている。この110年前としてはかなり「大判」のガラスが使われているので、より太陽光・日射取得型の意図を感じさせられる。いかにもより開放的な空間意図がそこに読み取れる。

しかし、開放感重視だけなら「掃き出し」で床までガラス戸であるべきなのに、窓の下には壁があってそうはしていない。やはり「寒冷地」を強く意識した中での開放感認識だったことがわかる。

で、このサンポーチは奥的な家族の空間、居間に隣接している。居間は畳敷きの和室。そしてサンポーチとの結界は引き違いの障子建具で仕切られている。やはり日本人の感覚としての居間と縁側・庭という感覚がベースにあったのだと知れる。サンポーチのガラス窓が大判ガラスで眺望重視であることとも合致する。

北海道では、いや現代日本では和室がリビングルームである住宅は、サザエさんの家くらいではないだろうか。

それくらい日本人は世界標準のライフスタイルとして「洋間」文化を受容してきたけれど、110年前の有島さんはこのあたり、かなり和洋折衷というテーマに立ち向かっているように思える。有島さんはこの家で1年半くらいを過ごしたのだけれど、和室の「こたつ」の中から降りしきるブリザードをこのサンポーチ越しに眺めていた。

きわめて感受性の強い有島武郎は、それまでの日本社会の「花鳥風月」をはるかに超える過酷な冬と、一転する乾燥した夏期を体感しながら、どんなふうに「拡張した花鳥風月」を感受していたのだろうか。日本人の感受性と北方の新開地・札幌の自然がどんな色模様を描いたのか、興味がいっそう深まる。

English version⬇

Western-style transformation of the porch “sun porch” Former Takeo Arishima’s residence-4

The Japanese people have an attachment to nature and have developed a sense of “kacho-fu-getsu” (flowers, birds, winds, and the moon). How did the Japanese transform their “Kacho-fu-getsu” sensibility by experiencing the cold and dry northern climate, which is far removed from the warm and humid climate of Japan? …

I decided to analyze Takeo Arishima’s residences in Sapporo as an extension of Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s temporary Japanese-style house in Kujukuri, because I was interested in the “residences of writers”. I began to think of it as the beginning of the history of housing design in Hokkaido.

I, as a human being, chose the domain of housing as the most Hokkaido-like theme from the desire to “create media in Hokkaido, and rich content at that,” but I feel as if I am being scolded by the great Mr. Arishima, who has gone far beyond Hokkaido, saying “Since you made such a choice, you should pursue the theme to the end” (laugh). You made that choice, so pursue the theme to the end” (laughs).

(Laughs.) No, I think it is a great blessing to be able to think that way.

Today, I would like to show you a “sun porch” that I have been wondering about in the drawings. 110 years ago, I wonder if Takeo Arishima, an English professor, was not aware of the general term “sunroom,” or if he felt it was more appropriate as a Western house type of “en-garashi” (porch) in the Japanese sense. Or perhaps he felt that this kind of word was more appropriate as a Western house type of “en-gawa” (porch), which is a Japanese concept.

Although the picture is not very clear, the windows in this area are not “raised windows” like the windows in the other rooms, but sliding windows and fittings are used in this room. The glass in the other rooms has a design shaped frame, but only this section is made of bare glass. The glass is quite “large” for this 110-year-old building, which gives the impression of an intention to obtain sunlight and solar radiation. The intention of a more open space can be read into the design.

However, there is a wall under the window, and if the emphasis is only on openness, it should be “swept out” with glass doors to the floor, but this is not the case. It is clear that the sense of openness was created with a strong awareness of the “cold climate” in mind.

This sun porch is adjacent to the back family space, the living room. The living room is a Japanese-style room with tatami mats. The sun porch is separated from the living room by a sliding shoji door. It is clear that the Japanese sense of a living room and porch was the base of the house. The large glass windows of the sun porch are also consistent with the emphasis on the view.

In Hokkaido, or perhaps in modern Japan, the only house in which the Japanese-style room is the living room is Sazae-san’s house.

Japanese people have accepted “Western-style” culture as the global standard lifestyle, but 110 years ago, Mr. Arishima seems to have been confronting the theme of blending Japanese and Western styles. Mr. Arishima spent about a year and a half in this house, and he used to watch the blizzard coming down from the kotatsu in the Japanese-style room through this sun porch.

I wonder how the extremely sensitive Takeo Arishima, experiencing the harsh winters and dry summers that far exceeded the “Kacho Fu Fugetsu” of Japanese society up to that time, perceived the “extended Kacho Fugetsu”. It will be interesting to see what kind of color patterns were created by the sensitivity of the Japanese people and the nature of Sapporo, a newly developed northern city.

Posted on 10月 19th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 住宅性能・設備

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.