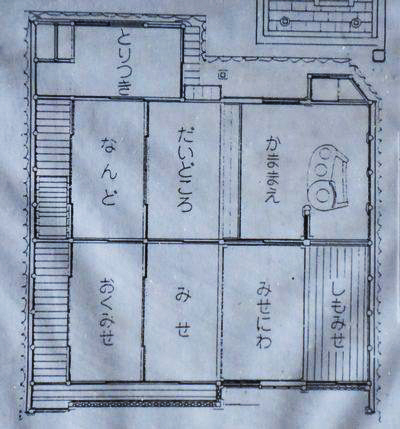

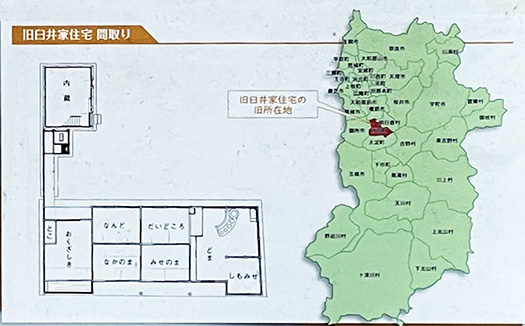

商家としての町家という日本の建築文化。

それぞれの「家業」に即していろいろなスタイルが存在した。

この家ではお米屋さんという生業のありようも垣間見える。

一方で、町家は職住一体感が非常に強く感じられる。

この家では自給的な井戸が残されていて

いかにも独立的生存装置のように思えて印象的だった。

日本の住文化というのはそもそもが職住一体が基本なのだと思う。

古建築住宅の場合、その暮らし・生き様がよくわからないのは、

武家住宅と長屋住宅に局限されるように思う。

長屋住宅は江戸で「奉公」するという形での生き方しかできなかった

農家の次男三男層が選択した生活環境。「一旗揚げる」気概を胸に

最初は極小面積賃貸に住み、そのなかでよりマシな階層に身分上昇し

ようやく同じ長屋での賃貸戸建てに住み所帯を構えるまでになれた人もいた。

商家に奉公した場合には番頭クラスになれた場合などに相当する。

そこからさらに身分上昇できると都市での戸建て住宅を得ることも

万に一つ、ありえたということだろう。商家奉公人の場合、暖簾分け相当。

きわめて機会の少ない「江戸での成功者」確率に

それでも挑戦せざるを得なかったひとの生き様も多数派だったのだと思う。

大部分の長屋賃貸生活者は、所帯を持てることもなく

江戸社会の中で安住を得ることは難しかったのだろうと思う。

江戸期に「個人主義」が芽生えるとすればこういう階層が

その主役になるべきだったろうけれどその確率はきわめてレアだった。

古代西洋社会、ローマなどの「市民」と「奴隷」の仕分けで見れば

体のいい奴隷だったともいえるのかもしれない。

ただ、日本社会は古代西洋のような過酷さはなく、

より人権的社会システムだったように思える。

すくなくともそういう階層が差別扱いをされるようなことはなかった。

一方、武家住宅を見ていると基本的に「生活感」が乏しい。

いかにも虚構の権威主義のなかで生きていたように感じられる。

「武士は食わねど高楊枝」みたいに空虚な虚栄心で心理を維持していた。

そのような江戸期「都市居住」類型のなかでは商家の職住一体感は

強い「生活感」をもって迫ってくる部分がある。

商家自身も江戸期社会の固定的家系でのシステムに組み込まれていたけれど、

しかしいちばん「自由」な生き方を生きていたように思う。

少なくとも商売についてはそれぞれの知恵と工夫で才覚を発揮もできただろう。

が、基本的には社会全体は武家支配という抑圧があり

突破する方向性としてはその支配構造を利用するしかなかっただろう。

商業の自由はなく「取り入る」という努力の仕方がやむなき選択。

個人的には田沼意次の政権が幕府でよりながく継続していれば、

江戸体制にも存続可能性があったと思うけれど、

「賄賂政治」だというバカげた他者非難で資本主義的社会進歩を抑圧した。

結果、そういう固陋な思考が幕末まで続いてしまったのだろう。

いま新しい資本主義というやや実態不明な題目を政権は掲げている。

より資本主義的な発展を図らない限り、この国の未来はない。

社会発展のダイナミズムはさてどういう動きの中から出てくるのでしょうか?

English version⬇

The Edo Period’s “Work and Residence Togetherness” of Town Houses: Yamato Historical Testimony-26

The Edo period, when society was fixed. The ruling class is too perverse, although elements of development can be found in the way of life of merchant families. The traditional art of condemnation of ridiculous ethics. …

The Japanese architectural culture of the machiya as a merchant house.

Various styles existed in line with each “family business.

In this house, we can catch a glimpse of a rice dealer’s business.

On the other hand, the machiya house has a very strong sense of unity between work and residence.

In this house, a self-sufficient well remains.

I was impressed by the fact that it seems to be an independent survival device.

I believe that the Japanese housing culture is based on the concept of “work and residence as one.

In the case of old houses, it is difficult to understand the lifestyle of the residents.

In the case of old houses, I think that the lack of understanding of the way of life is limited to samurai residences and tenement houses.

The tenement houses were the only way of life for the second and third sons of farmers who could only live as “servants” in Edo.

The second and third sons of farmers chose this type of living environment. With the spirit of “making a name for themselves

They first lived in a very small rented house, and then moved up to a better class within the family.

Some of them finally managed to live in a rented house in the same tenement and set up their own household.

In the case of those who were apprenticed to a merchant family, this would be equivalent to being in the banto class.

If you were able to rise further in rank, you could even get a detached house in the city.

This was a one-in-a-thousand chance. In the case of merchant family servants, it is the equivalent of being a “noren-keisatsu” (goodwill divider).

The probability of being a “successful person in Edo” was extremely low.

I believe that there were many people who had no choice but to take up the challenge.

Most of the tenement renters were not able to have their own families.

It would have been difficult for them to find a safe haven in Edo society.

If “individualism” was to sprout in the Edo period

However, the probability of such a situation was extremely rare.

If we look at ancient Western societies, such as Rome, and sort out “citizens” and “slaves

It could be said that they were slaves in the sense that they were good for the body.

However, Japanese society was not as harsh as that of the ancient West.

It seems that Japanese society was not as harsh as that of the ancient West, but was a more human rights-oriented social system.

At the very least, such classes were not discriminated against.

On the other hand, when we look at samurai residences, there is basically a lack of a “sense of life.

It is as if they were living in a fictional authoritarianism.

They maintained their mentality with an empty sense of vanity, as if to say, “Samurai don’t eat, but they do eat.

In this type of “urban residence” of the Edo period, the sense of unity of work and residence of the merchant family

The merchant family itself was part of the fixed family system of Edo period society, but it was also a part of the family system of the Edo period.

Although merchant families themselves were part of the fixed family system of Edo period society

However, I think they lived the most “free” way of life.

At least in the area of business, they were able to exercise their own wisdom and ingenuity.

However, the society as a whole was basically under the oppression of samurai rule, and the direction to break through the oppression was to use the structure of that rule.

The only way to break through this oppression would have been to take advantage of the ruling structure.

There was no freedom of commerce, and the only choice was to “take in” the oppressor’s efforts.

Personally, I believe that if Tanuma Iiji’s regime had continued in the Bakufu for a longer period of time, the Edo system would have been more viable.

I think the Edo system would have had a chance of survival if Tanuma Iiji’s regime had lasted longer in the Bakufu.

However, he suppressed capitalist social progress by ridiculously accusing others of “bribe politics.

As a result, such perverse thinking continued until the end of the Edo period.

Now, the regime is raising the somewhat unrealistic title of “new capitalism.

There is no future for this country unless it pursues a more capitalist development.

What kind of dynamic of social development will emerge from this movement?

Posted on 7月 23rd, 2022 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »