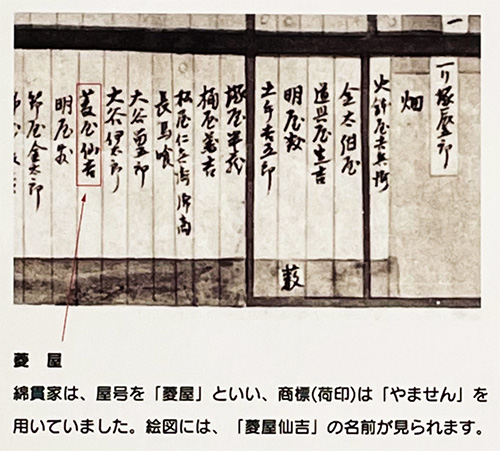

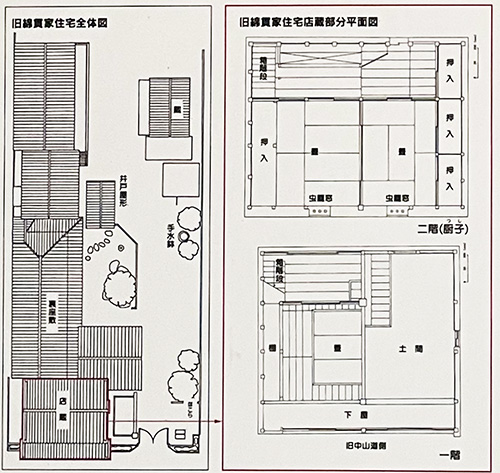

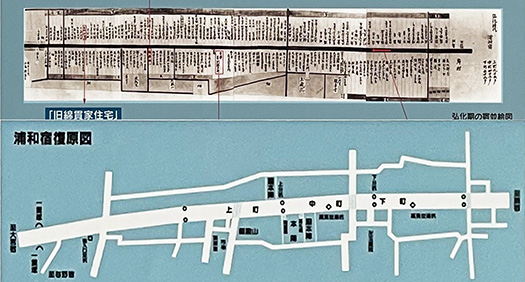

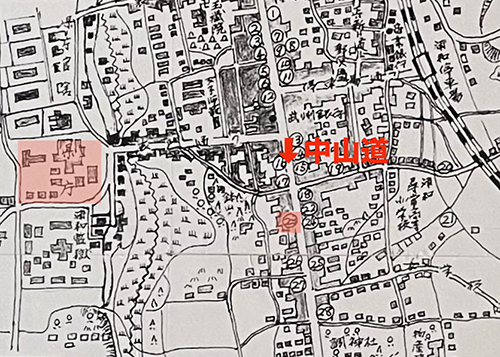

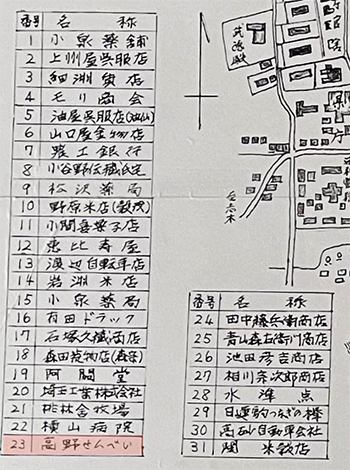

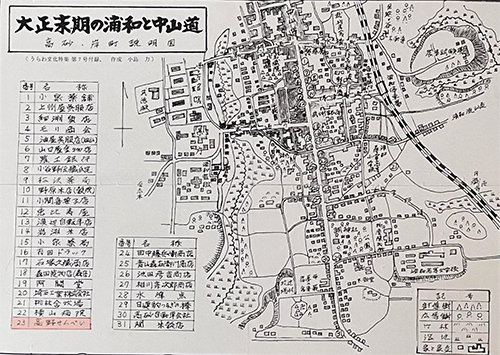

この浦和宿の荒物(雑貨)肥料店舗・旧綿貫家は、江戸時代後期には確実に浦和で商家を営んでいた。1844年当時に描かれた「宿並絵図」に記録が残されている。周辺環境は農業が主体の地域だから、比較的に需要の多い店舗だったのだろうと推測できる。

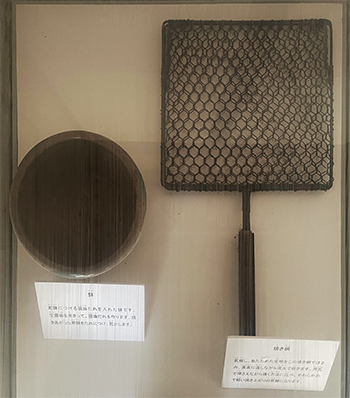

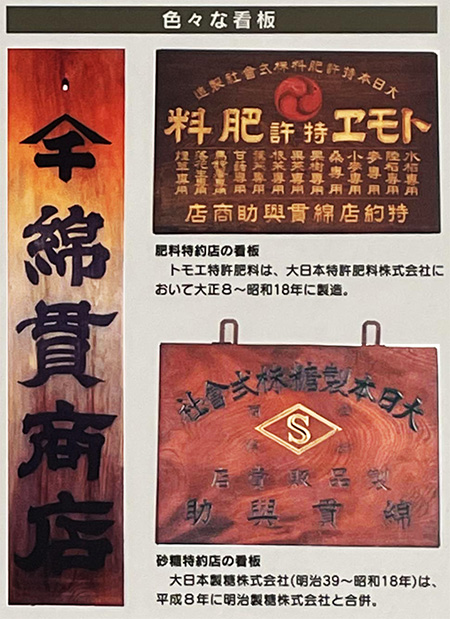

荒物とはザルやホウキ、チリトリなどの雑貨が主体。一方の肥料店はメインの肥料をはじめ砂糖・小麦などの仲卸と大口客相手の取引を営んでいたのだという。肥料にもそれぞれの作物毎に最適化された品種が存在して売買されていたことがわかる。

さらに浦和宿には、大名の参勤交代の旅宿があったとされている。東北地方・関東北部の大名家が行列を組んで大名自身は「本陣」と言われるメイン旅宿に泊まり、その他の随行員たちは「脇本陣」と呼ばれる旅宿に泊まった。この浦和宿の本陣は「星野権兵衛家」という家系が代々取り仕切っていたという。本陣敷地は約4000㎡(約1200坪)、主屋は700㎡(212坪)という広大な面積を誇っていたとされる。この建物は現在現存せず、その敷地跡には明治天皇がさいたま市の氷川神社行幸の折に立ち寄った記念碑が建てられている。江戸期の宿場町経済の実態を伝えているようです。

わが家の家系伝承では先祖たちは広島県福山市の山陽道・今津宿で、国造以来の家柄の名家「河本家」が営んでいた「今津本陣」とのビジネスで「英賀屋」という屋号で商家を営んでいた。江戸期の経済実態とは、こうした宿場町経済が地方においては中核的なビジネスだったのだとわかる。

肥前平戸の9代藩主・松浦静山が描いた「甲子夜話」に、宿泊した「今津本陣」での旅宿側の勤労奉仕ぶりが描かれているなかにわたしの先祖の動静も記されています。参勤交代という社会システムが地域経済にとってどういうものだったのかがよくわかる。江戸期の商業にとっていかに巨大機会であったことか。

そうした中核的なビジネスがあってさらに周辺的な商品・サービスが宿場町には集中していたのだろう。たまたま同様の宿場町の様子が保存移築されている浦和宿の様子から、わが家のことまでまざまざと先人の息づかいが皮膚感覚で伝わってくるような思いがする。

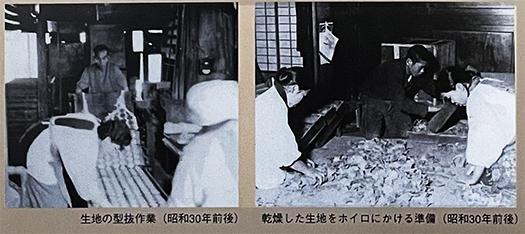

ということから若干スピンアウトして、昭和30年代(1958年)当時、札幌市中央区北3条西11丁目で食品製造業を生業としていた当時のわが家の古い写真です。先日、浦和宿の煎餅屋さんの生業の様子を見たけれど、よく似たような写真で、若かった父親が中央で生産現場を見ている様子。食品製造の最終工程なのですが、その視線には先日の煎餅屋さんのご主人とおぼしき方と似た必死さが表れている。

江戸期から昭和30年代というスパンで見ても、日本人の経済の営みは連綿と受け継がれてきている感覚・同一感がある。180年前後の時間空間が通底してくるのですね。歴史時間の重量感。

English version⬇

The Postal Town and Market Economy: Townhouses in Urawa-juku on the Nakasendo Highway – 6

The actual situation of the economy of the inn town in the Edo period can be seen like a perspective drawing. The time of 180 years before and after the Edo period and the breath of the predecessors come together in one span of time. The house is a townhouse.

The former Watanuki family, which operated a fertilizer store in Urawa-juku, was certainly a merchant in Urawa in the late Edo period (1603-1868), as recorded in “Shukuninami Ezu” drawn in 1844. Since the surrounding environment is primarily agricultural, it can be assumed that the stores were in relatively high demand.

Rough goods are mainly miscellaneous goods such as colanders, brooms, and dust trimmers. The fertilizer store, on the other hand, was a wholesaler of fertilizers, sugar, wheat, and other commodities, and also dealt with large customers. It is evident that fertilizers were sold and traded in varieties optimized for each crop.

Furthermore, it is said that Urawa-juku was also a traveling inn for daimyo daimyo’s daimyo’s visits to the area. Daimyo families from the Tohoku region and the northern part of Kanto formed a procession, and the daimyo themselves stayed at the main traveling inn called “Honjin,” while the other attendants stayed at the “Wakihonjin,” or side inn. The main camp at Urawa-juku was managed by a family called “Hoshino Gonpei Family” for generations. The main camp site was approximately 4,000 square meters (about 1,200 tsubo), and the main building boasted a vast area of 700 square meters (212 tsubo). The building no longer exists, and a monument stands on the site where the Emperor Meiji stopped by during his visit to Hikawa Shrine in Saitama City. It seems to convey the reality of the inn town economy during the Edo period.

According to our family tradition, our ancestors ran a merchant house under the trade name of “Eigaya” in Imazujuku on the Sanyo Road in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, in business with the Imazu Honjin, which was run by the Kawamoto family, a prominent family since the Kokuzo period. The economic reality of the Edo period shows that this kind of lodging town economy was a core business in the local region.

In the “Koshi Yawa (Tales of Koshi)” written by Shizan Matsuura, the ninth lord of Hirado, Hizen Hirado, the movements of my ancestors are described in the description of the labor service of the innkeepers at the “Imazu Honjin” where the innkeepers stayed. It is easy to see how the social system of “Kan-kodogodai” (pilgrimage to and from work) was important to the local economy. It is clear what a huge opportunity it was for commerce in the Edo period.

With such core businesses in place, there must have been a concentration of peripheral goods and services in the inn towns. The Urawa-juku, which happens to be a preserved and reconstructed example of a similar inn town, gives me the feeling that I can feel the breath of my predecessors in my own home.

So, spinning out slightly from this, here is an old photo of our house at the time of the 1950s (1958), when we were making a living as a food manufacturing business in Kita 3-jo Nishi 11-chome, Chuo-ku, Sapporo. The other day, I saw a picture of a cracker shop in Urawa-juku, which was a very similar picture, but the father, who was young, is in the center watching the production site. It is the final process of food production, and his gaze shows a desperation similar to that of the owner of the senbei shop the other day.

The time-space of around 180 years is at the bottom of the story. The weight of historical time.

Posted on 7月 15th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »