当たり前のことですが、日本人は社会の中で必死に生きてきた。わたしたちが現在にまで生き延びてきたのは、先人たちが必死に生業を営んできたことのおかげ。この浦和の古民家には強く感じさせられる。

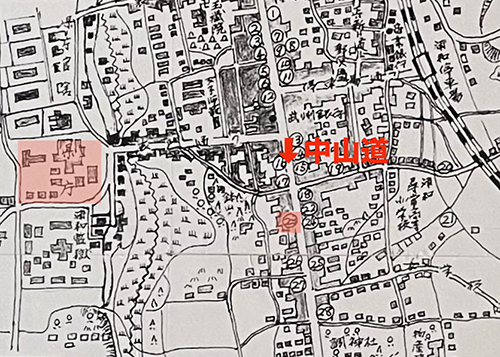

という感覚には時代背景、この煎餅店の立地、生業ともわたしの生家と近似点が多いことがある。幕末から明治の混乱期にこの家は大きな街道筋である中山道に面した立地で、そこそこの都会である浦和で、たぶん旅人などの移動者に対して、食品を提供していのちを繋いできた。

わたしの生家は、札幌の石山通という南北の幹線道路に面した敷地で食品製造業を戦後の混乱・復興期から開始して、なんとか家族を養ってきた。

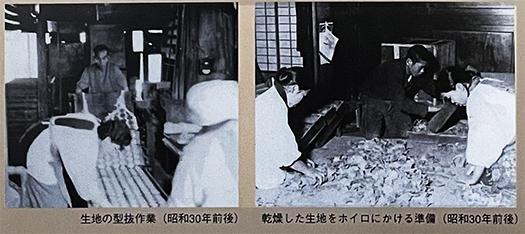

展示されていた家内制手工業らしい生産風景の写真に見入っていて、わが家との類似性に激しく共感の思いを抱いた次第なのです。撮影されている女性たちの表情に母親の面影をすら感じてしまう。

街道に対して間口を大きく開口して道行く人たちに手軽な食品を提供することで、いつの世にも確実な食品で生業を確保しようという生存戦略。わたし自身はまだ3才だったので、そのような父母の考え方はわからなかったけれど、戦後の混乱期を超えてそれまでの農家をやめて札幌という北海道最大の都市に一家を挙げて移住したという、そういう生き方の選択ではまったく同じように感じている。

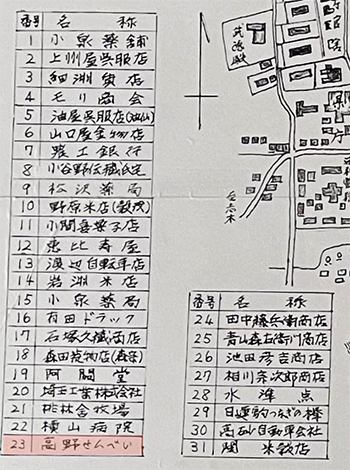

そんなふうな感慨を持って見ていると、当時の街路地図、そこに表現された商店名などにもどこか、既視体験のような空気感を感じさせられる。もっと言えば、活字ではなく手書きと思われる文字にも、それ以前の日本社会からの伝統的価値感のようなものまで匂い立っている。

わたしたち社会の根源の姿、その一端が表現されている。

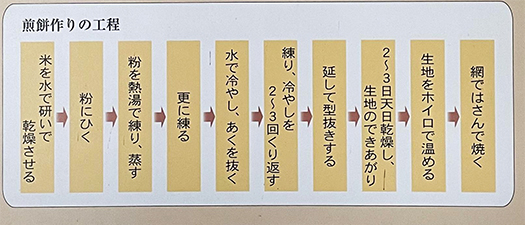

〜「せんべい」の起源は、空海が中国から持ち帰った説、千利休の弟子が考案した菓子の由来説、草加のおせんさんという人が旅人から教わって団子の残りを焼いたのが始まり説とか、種々言い伝えがある。団子状のもちを焼いて食べることは弥生時代にはすでに普及していた。しかしこれはあくまでも主食で、間食として菓子の性格を持つものは室町時代以降であり、江戸時代になって多くの名物せんべいが誕生した。江戸時代に「せんべい」と称したのは小麦粉に砂糖を混ぜて練り焼いたもの。「塩せんべい」は下級品とされ、農家が残り飯を煎って蒸し塩を混ぜて伸ばしてから竹筒で丸形に抜き、天日干しして炭火で焼いたのが始まりとされる。塩せんべいにしょうゆが用いられ現在のようになるのは1645年以降。江戸に近い町屋、千住、金町、柴又、草加などで繁盛した。とりわけ奥州街道宿場町・草加の「草加せんべい」は「塩せんべい」を代表するほどの人気となった。・・・参考/全国米菓工業組合「米菓とともに半世紀(50周年記念誌)」〜

弥生時代かよ(笑)。まことに深遠な日本人の食の世界。・・・

English version⬇

Nostalgic Domestic Food Handicraft Industry: Nakasendo, Urawa’s Sembei Shop-2

The universal survival strategy of the Japanese people from their parents’ generation to prehistory. The unchanging business of food production. The control of the cultural flow path called “Kaidou-suji”. The

Japanese people have struggled to survive in society. We have survived to the present day thanks to the desperate efforts of our predecessors to make a living. This is a matter of course, but this old house in Urawa makes me feel it strongly.

The reason is that the historical background, the location of this rice cracker store, and its business have many similarities to my family’s. The house was built during the period of turmoil from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period. During the turmoil from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period, this house was located facing Nakasendo, a major roadway in Urawa, which is a reasonably urban area, and probably provided food to travelers and other mobile people to sustain their lives.

My family started a food manufacturing business on a site facing Ishiyama-dori, a major north-south road in Sapporo, during the postwar turmoil and reconstruction period, and has managed to support my family.

As I looked at the photos on display of production scenes that were typical of a cottage industry, I felt a strong sense of empathy for the similarities with my own family. The women in the photographs even have the look of their mothers on their faces.

The strategy of survival is to secure a livelihood with reliable food products by opening a wide frontage to the street and offering easy food products to people on the street. I myself was only 3 years old, so I did not understand such a way of thinking of my parents, but I feel the same way about their choice of life, which was to quit farming and move to Sapporo, the largest city in Hokkaido, after the chaos of the postwar period.

Looking at the map with this kind of emotion, the street maps of the time and the names of stores expressed on them also give one a sense of déjà vu. More specifically, even the handwriting, which appears to be handwritten rather than typed, evokes a sense of traditional values from the Japanese society of earlier times.

The work expresses a part of the roots of our society.

〜The origin of “senbei” is said to have been brought back from China by Kukai, or from a confection invented by a disciple of Sen no Rikyu, or from a baked dumpling leftover by a Soka resident named Osen-san, who learned it from a traveler. The practice of baking and eating dumpling-shaped glutinous rice cakes was already widespread during the Yayoi period (710-794). However, this was only a staple food, and it was not until the Muromachi period (1333-1573) that it took on the character of a snack, and it was not until the Edo period (1603-1867) that many specialty rice crackers were born. In the Edo period, “senbei” were made by kneading and baking wheat flour mixed with sugar. Shio senbei” was considered a lower class product, and is said to have originated when farmers roasted leftover rice, mixed it with salt, stretched it out, cut it into rounds in bamboo tubes, dried it in the sun, and baked it over a charcoal fire. It was not until 1645 that soy sauce was added to salt rice crackers. They thrived in the town houses near Edo (Tokyo), such as Senju, Kanamachi, Shibamata, and Soka. In particular, “Soka senbei” from Soka, a post town on the Oshu highway, became so popular that it represented “shio senbei” (salted rice cracker). Reference: National Rice Cracker Industry Association, “Half a Century with Rice Crackers (50th anniversary commemorative magazine)

The Yayoi Period? The world of Japanese people’s food is truly profound. ….

Posted on 7月 10th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 古民家シリーズ

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.