浦和民家園」を探訪するシリーズ第4回目。このシリーズの第一回目はこちら→【関東の古民家探訪「中山道の高野煎餅店」-1】

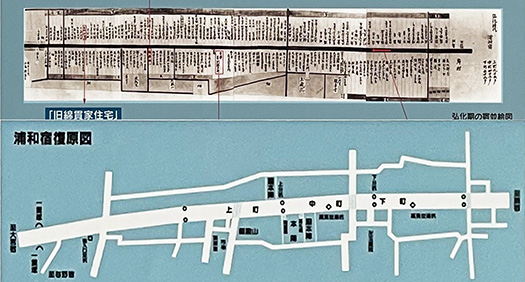

街道筋に面した立地というのは多様な人びとの交易・交流を基本に置いた「地割り」。間口が狭く、奥行きが長い敷地形状が合理的な土地利用法となっている。「町家型土地計画」とでも呼べるのでしょう。

日本では京都の町家がひとつの典型とされるけれど、別に京都だけに特別なものではなく、全国どこの地域でも普遍的にこの考え方で街区が形成された。民族の最新大都市である札幌でも「狸小路」が自然に生成した。

間口を狭くすることでたくさんの商家が単位距離あたりで密集性が高まって原初的な「にぎわい」演出として成立していったのだと思います。さまざまな商品・サービスが一覧的に展示されることで、ひとびとの購買意欲を高めていった効果があるのでしょう。たぶん人類普遍的な街区形成。多様な人間生活の要求に即して、しかもそれらが人間の交流を通して人情味ある発展をもたらしてきた。オープンな姿勢で入口を広く開口して、土間・小上がり的なお迎えインテリア空間+生業のための開放的空間。

で、わたし自身もこういった街区が醸し出す人間交流の雰囲気のなかでこころが揺籃されていたと気付かせられる。この浦和の町家街区での深掘りで人びとの営みが非常に近しく感じられてならない。

一方で、戦後の高度成長・人口増加ではいわゆる「住宅専用地域」という、生業とは直接関連しない街区・住宅が大量生産されていった。現代での家づくりでは、基本的にこうした土地計画が主流になり、その街区の特徴・雰囲気とはほぼ無縁な平均的な街が形成されてきている。住宅も、街区とのかかわり、人びとのにぎわいとの調和という志向は基本的に持たない「個人主義的」な家づくりになってきていると言える。知人にはこういう現代住宅のデザインルーツとして生業を持たない江戸期の中級武家住宅を挙げるひともいる。

こうした現代型の都市計画と普遍的な伝統的町家建築・住宅との関係性・断絶性についてあまり考慮しなくなっていることに気付かされる次第。かつての町家街区では向こう三軒、両隣的な近隣との人間関係が強く存在していたけれど、現代住宅街ではそういった部分は希薄化してきている趨勢。

家づくりを考えて行くに当たって、こうした人間関係の環境要因について再度立ち止まって考えて見ることも重要なのではないだろうか。人間社会ではある方向に極端化が進んでいくと、反対側の要素が「揺り戻し」のような反応を見せて、やがて調和ということを志向するようになる。だとすると、見ているような「町家街区」が持っていたよき側面について考え直し、現代住宅に取り戻していくことが求められる可能性がある。

高断熱高気密化という肌感覚の進化要因のはるか先に生まれてくる住の需要要素として、そうした萌芽を注意深く見ていく必要性がある。言ってみれば「いごこち」の生体科学的満足度追求と、そのさらに先には別の環境的満足度要因が見出されていくということか。思索を温めていきたい。

English version⬇

Machiya lot layout and modern residential area: Nakasendo and Urawa rice cracker shop-4

Open architectural space to the street. Spatial design that gives full consideration to human interaction. What is the future of the modern closed town and housing? ・・・・.

The location facing a street is a “lot layout” based on trade and exchange among various people. The narrow frontage and long depth of the site make it a rational land use method. It could be called “machiya-style land planning.

In Japan, machiya houses in Kyoto are considered to be a typical example, but they are not unique to Kyoto, and town blocks were universally formed based on this concept in all regions of Japan. Even in Sapporo, the newest metropolis of Japan, “Raccoon Alley” was created naturally.

I believe that by narrowing the frontage, many merchant houses became more densely packed per unit distance, and it was established as a primitive “bustling” production. The display of a variety of products and services in a single location may have had the effect of increasing people’s willingness to purchase. Perhaps this is the universal formation of city blocks for human beings. The development of the district is in line with the diverse needs of human life, and has brought about humane development through human interaction. The open attitude, wide opening of the entrance, welcoming interior space like an earthen floor or a small room, and an open space for living and working.

I myself have been cradled in the atmosphere of human interaction created by these townhouses. The machiya district in Urawa has made me feel very close to the lives of the people.

On the other hand, during the postwar period of rapid economic growth and population increase, so-called “residential areas” were mass-produced, which were districts and houses that were not directly related to people’s livelihoods. In modern house building, such land planning has basically become the mainstream, and average towns have been formed that have almost nothing to do with the characteristics and atmosphere of the township. Houses are now being built in an “individualistic” manner, with basically no orientation toward harmony with the neighborhood or the bustle of the people. Some of my acquaintances point to the Edo period (1603-1868) middle-class samurai residences with no business as the design roots of these modern houses.

I am reminded that we no longer give much thought to the relationship and disconnect between modern urban planning and traditional machiya architecture and housing. In the past, machiya townhouses had a strong relationship with their neighbors, as if they were the other three houses or two neighbors, but in modern residential areas, such relationships are becoming less and less common.

When considering how to build a house, it is important to stop and think about these environmental factors of human relationships. In human society, when extremes are advanced in one direction, the opposite elements react in a “swinging back” manner, and eventually, the society will start to seek for harmony. If this is the case, it may be necessary to reconsider the good aspects of the “machiya district,” as we are seeing it, and bring them back into modern housing.

We need to carefully watch for the emergence of such a demand element for housing, which will emerge far beyond the evolutionary factor of high thermal insulation and high airtightness. In other words, we are pursuing bioscientific satisfaction in terms of “comfort,” and furthermore, we will discover another environmental satisfaction factor. I would like to continue my contemplation.

Posted on 7月 13th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 「都市の快適」研究, 住宅マーケティング

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.