街道筋の立地を活かした「煎餅店」の看板と「店先」の様子がわかる写真。そして広い土間では毎日、煎餅製造の作業が繰り返された。使い込まれたカマドからは、まさに生業を支えた火力の力強さを感じさせられる。

3枚目の写真は昭和30年代のこの家での「生業」の様子とされている。個人的にわたしの父と面影が近似している。・・・江戸期までの社会は農業を基本立国戦略とした社会。武家支配の体制で米の石高によって経済の基本が計量された社会だけれど、田沼時代など、市場経済重視の「改革」も試みられていた。

明治の変革で関西経済を牛耳っていた三井や住友などの旧財閥系が出資することで明治政府軍が江戸幕府の体制をひっくり返すのだけれど、市場経済的社会発展の方向で大きく社会は変換していった。そういう社会改造は昭和まで継続してきたともいえる。

この浦和の煎餅店にはそういう社会変革の空気感が伝わってくる。

以前には栃木県宇都宮の駅前に今でも残っている商家を探訪したこともあるけれど、江戸期の市場経済、都市経済の実質が関東各地では一部で濃厚に残されてきている。たぶん江戸の街というのはこういった商家・家内制手工業の家が軒を接して街区を形成していたのに違いない。江戸から東京に一変していく中で都市景観のそうした残滓はほぼ一掃されていったのだろう。というか、最先端としてどんどんスクラップアンドビルドが進展して江戸社会の状況は感じられなくなっていったのだろう。

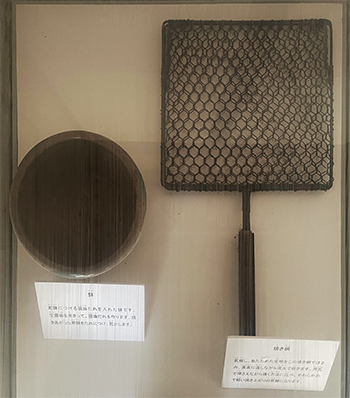

煎餅の原材料をこねて上の「型」で型抜きして、カマドに懸けた油で揚げて、醬油ダレなどにくぐらせてから網焼きした工程が写真展示されていた。写真を見る限り「家内制」というよりも近隣の女性労働力に支えられてこの家の生産は維持されていたように思う。この街道に面した建物部分は、生産の場、ビジネスの場として特化された空間だったのだろう。

ちょうどわたしの生家でも昭和30年代、こうした家内制手工業そのままの生業が営まれていた。わが家では男兄弟が5人いたので、それが労働主体となって生産が回転していた。徐々にパートなどの労働力が投入されていって事業規模が拡大した。生産労働の現場感、その雰囲気が通底していて、えぐられるような感覚を持ってしまう。子どもたちは早朝から必死の生産労働に従事した後、食事して学校に通っていた。わたしたち年代でようやく、周囲に「サラリーマン」世帯が居住するようになったけれど、子どもたちの家の大方はこうした生業感を維持していた。

令和の今の時代では、街からこうした息吹は消えて行きつつあるけれど、日本の都市の成立期とはこのような空気感がベースなのだと思える。意識的な文化継承が必要ではないだろうか。

English version⬇

The Architecture of Means of Survival in the City: Nakasendo, Urawa’s Sembei Shop – 3

Just 40-50 years ago, the air of subsistence was everywhere in Japanese cities. Is the modern “house just for living” really progress? …

This photo shows the signboard and “storefront” of a “sembei store” taking advantage of its location on a street. In the large earthen floor, the rice cracker manufacturing process was repeated every day. The well-worn kamado (a kind of wooden stove) shows the power of the fire that sustained the business.

The third photo is said to show the “livelihood” of this house in the 1950s. Personally, it is a close resemblance to my father. …Until the Edo period, society was based on agriculture as a basic national strategy. The economy was based on the amount of rice produced under the samurai rule, but during the Tanuma period, there were attempts at “reforms” that emphasized a market economy.

The Meiji government forces overturned the Edo shogunate system by investing in the former zaibatsu groups such as Mitsui and Sumitomo, which had controlled the Kansai economy during the Meiji Restructuring. Such social transformation can be said to have continued until the Showa period.

This rice cracker store in Urawa conveys the atmosphere of such social reform.

I once visited a merchant’s house that still remains in front of a station in Utsunomiya, Tochigi Prefecture, and the substance of the market and urban economy of the Edo period is still strong in some parts of the Kanto region. The streets of Edo (present-day Tokyo) were probably made up of such merchant and cottage industry houses. As the city changed from Edo to Tokyo, these remnants of the urban landscape were almost completely wiped out. In other words, the state-of-the-art scrap-and-build process has progressed rapidly, and the conditions of Edo society can no longer be felt.

The photo exhibit showed the process of kneading the raw ingredients for the rice crackers, cutting them into molds, frying them in oil over a kamado, dipping them in shoyu sauce, and then grilling them. The photos suggest that the family’s production was maintained by the female labor force of the neighborhood, rather than a “cottage industry. The part of the building facing the street must have been a specialized space for production and business.

In the 1950s, my family was engaged in this type of cottage industry. There were five male siblings in my family, so production revolved around them as the main labor force. Gradually, part-time and other workers were brought in, and the scale of the business expanded. The on-site feeling of production labor and its atmosphere is so pervasive that it has a gut-wrenching effect. Children were engaged in frantic production labor from early in the morning, and then had to eat and go to school. Although “salaried” households finally began to populate the neighborhoods around my generation, most of my children’s families maintained this kind of work ethic.

In the current era of 2025, this kind of atmosphere is disappearing from the city, but I believe that the founding period of Japanese cities was based on this kind of atmosphere. We need to consciously carry on this culture.

Posted on 7月 12th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.