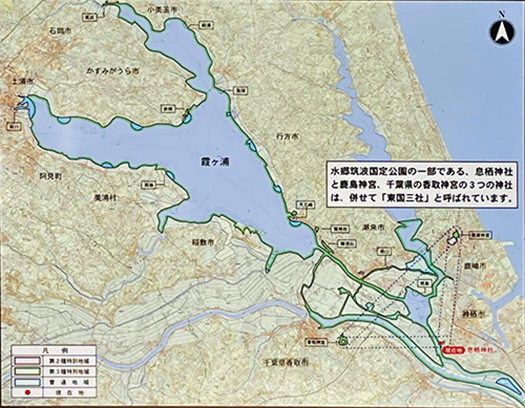

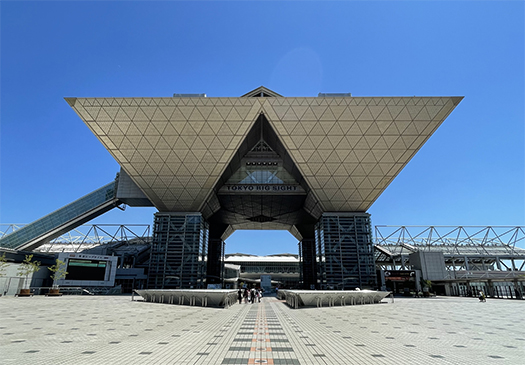

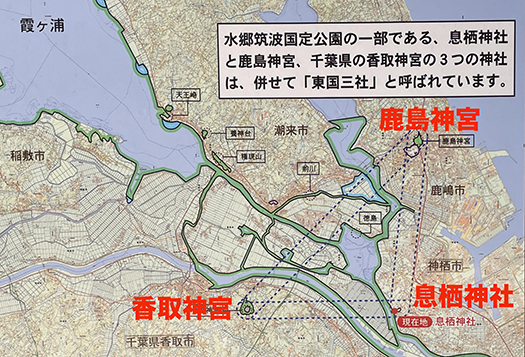

先週には日曜日をまたいで、東京・関東に滞在していました。また再び東京ビッグサイトでのイベントにも参加してきたのですが、時間を見つけて休日にはこのブログの取材も兼ねて「鹿島神宮」と香取神宮、息栖神社の東国三社をライフワークとして取材行脚(?)していました。

東京都内から炎暑のなか、レンタカーを借りて一路、この地域まで。

都内滞在中はほぼ電車移動なので、SUICAは移動の基本手形。移動目的地までの交通手段は「乗換案内」などのアプリを利用すれば瞬時に最短ルートを示してくれる。SUICAさえあれば、こういう移動のメンドくささはほぼなくなる。炎暑の中だけれど便利に移動できるのはありがたい。

しかしやはり暑いので薄着なので、手荷物類の衣類収納、ポケット収納は限定的になる。

わたしの場合、ウェストポーチにもなるショルダーポーチメインでほぼ収納し、小銭入れやSUICA、ハンカチなどをズボンポケットに収納していた。とくに神社仏閣などでは小銭入れからお賽銭を出したりするので小銭入れとSUICAは仲良く同居する。

鹿島神宮地域まではクルマだったのでこのような収納スタイルは本来不要だったけれど、都内移動での常態からあんまり変えると不意に「あれどこだっけ?」と失念することがあり得るので、スタイルは変えなかった。

で、鹿島神宮でありがたく参拝させていただいて、祭神・武甕槌大神(たけみかづちおおかみ)との再会を言祝がせていただいた。その後、前述の東国三社を巡り歩き、ホテルに戻った。

ふと気付いてSUICAを探したけれど見当たらない。どうも小銭入れから賽銭を出したとき、SUICAは随伴して転げ落ちてしまったようだ。ちょうどチャージもしていたので残額は10,000円前後。もったいないし、ひょっとしてそれ以上にカードが悪用されることもあり得る。最近物騒。で、ググってみたらJRのHPで「新幹線の駅のみどりの窓口」で紛失届すると再発行手続きできるとあった。

で、届け出たら再発行SUICAは翌日以降の手渡しでその期間も2週間以内限定になるという。これはどういう根拠からの決まりなのかは、問い合わせても不明だった。しかも札幌はJR北海道管内でありJR東日本とは別会社なので札幌に帰ったら事実上もうムリとのこと。残念ながら帰還はこの日の夕方だったのです。

個人名入りのSUICAなので個人情報は容易に特定可能ですべてWEB上での処置が可能なはずで、この決まりの根拠はユーザーには理解不能。手続きしてくれた窓口の女性の方も「わたしも、ヘンだと・・・」思うということ。

まぁしかしやむを得ないので、手続きだけはして無用の悪用可能性を除去することにした。

で、当日の要件を片付けて札幌帰還後の翌日昼過ぎになって、ケータイに着信。

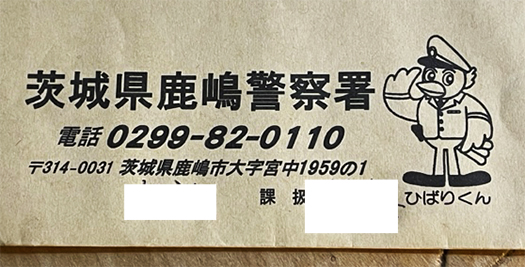

連絡者は鹿島神宮管轄の警察署からで、件のSUICAが落とし物届け出されたという連絡。おお、であります。そのプロセスを考えて見れば、多数の関東のみなさんの善意の積み重ねが見えてくる。落とし物を発見して,警察に届け出てくれたこと。そして警察の方は個人情報にアクセスしてわたしの電話番号を探して丁寧に電話連絡してくれたこと。まことに鹿島神宮の霊験としか考えようがない。

・・・ちょっとブログとしては長文になりすぎるので以下は、あしたへ。

English version⬇

The Sacred Spirit of Kashima Jingu Shrine, Lost and Found SUICA Return-1

The blessings of Takemikazuchi Okami, the deity of the shrine, who loves justice. He descended to us, the poor travelers. …….

Last week I was in Tokyo and Kanto over Sunday. I also attended an event at Tokyo Big Sight again, and on my days off, I found time to visit the “Kashima Jingu Shrine,” Katori Jingu Shrine, and the three shrines in the eastern part of Japan to do research for this blog as part of my life’s work (?). I was in the middle of a hot summer day in Tokyo.

I rented a car and drove all the way from Tokyo to this area in the blazing heat.

Since most of my time in Tokyo is spent traveling by train, SUICA is my basic bill for transportation. If I have SUICA, the hassle of such travel is almost eliminated. It is nice to be able to move around conveniently in the blazing heat.

However, since it is still hot and I am wearing light clothing, the storage space for my hand luggage in my clothes and pockets is limited.

In my case, I used a shoulder pouch that doubles as a waist pouch for most of my luggage, while I stored my coin purse, SUICA, handkerchief, etc. in my pants pocket. Especially at shrines and temples, I would take out money offerings from the coin purse, so the coin purse and SUICA lived together in harmony.

Since I drove to the Kashima Jingu area, this style of storage was unnecessary, but I did not change it because I might lose it unexpectedly if I changed it too much from the usual way of traveling in Tokyo.

I was grateful for the opportunity to visit the Kashima Jingu Shrine, where I was reunited with Takemikazuchi Okami, the deity of the shrine. After that, I walked around the three shrines in the eastern part of Japan mentioned above and returned to the hotel.

I suddenly realized that I had looked for my SUICA, but could not find it. It seemed that when I took out my money from the coin purse, the SUICA fell down with it. I had just recharged it, so the remaining amount was around 10,000 yen. It was a waste of money, and there was a possibility that the card could have been misused for more than that. So I googled and found on JR’s website that you can report the loss of your card at the Midori-no-madoguchi (ticket counter) of Shinkansen stations and they will reissue a new card.

I found out that if you report the loss, the reissued SUICA will be handed over to you the next day or later, and only for a period of two weeks or less. I inquired as to the reason for this rule, but it was unclear. Furthermore, since Sapporo is under the jurisdiction of JR Hokkaido, which is a separate company from JR Kanto, it would be virtually impossible to return to Sapporo. Unfortunately, the return trip was that evening.

Since the SUICA has a personal name on it, everything should be able to be handled on the web, and the rationale for this rule is incomprehensible to users. The lady at the counter who took care of the procedure also said, “I also think it’s strange…”.

Well, it was unavoidable, so I decided to just go through the procedure and eliminate the possibility of unnecessary abuse.

The next day, after I had completed the day’s requirements and returned to Sapporo, I received a call on my cell phone in the early afternoon.

The caller was from the police station with jurisdiction over Kashima Jingu Shrine, informing that the SUICA in question had been reported as a lost property. Oh, yes. If you think about the process, you can see the accumulation of the goodwill of many people in Kanto. The fact that they found the lost item and reported it to the police. The police accessed my personal information, found my phone number, and politely called me. I can only think of it as a spiritual blessing of Kashima Jingu Shrine.

…This is a bit too long for a blog, so I’ll leave the rest for tomorrow.

Posted on 8月 3rd, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »