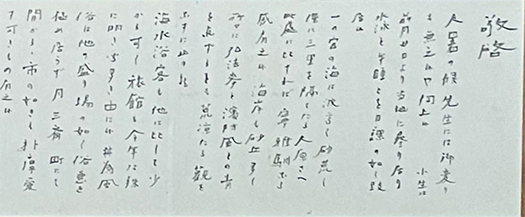

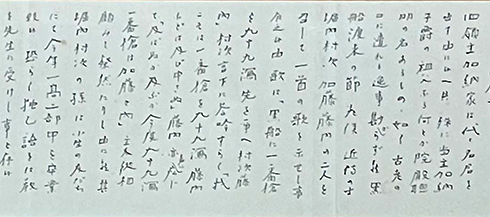

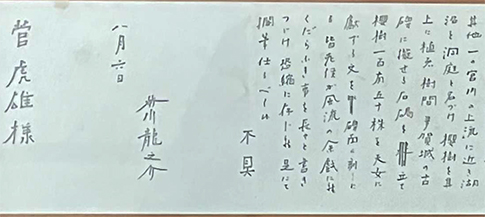

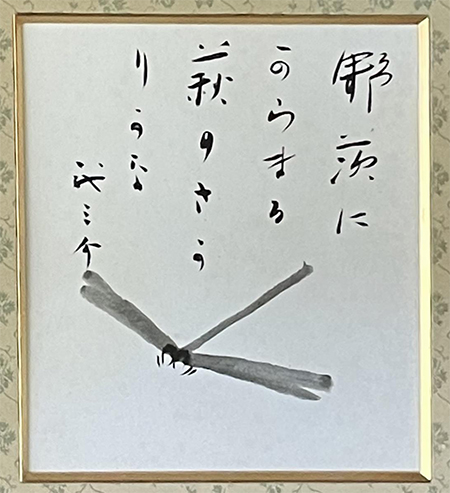

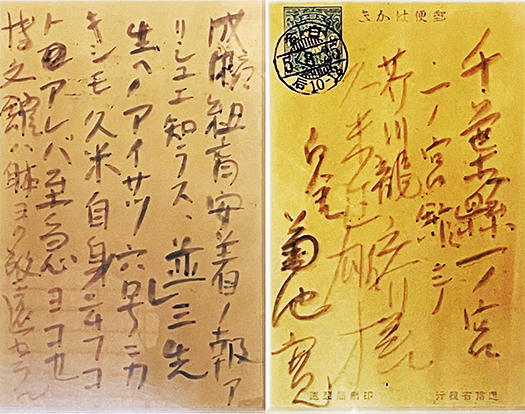

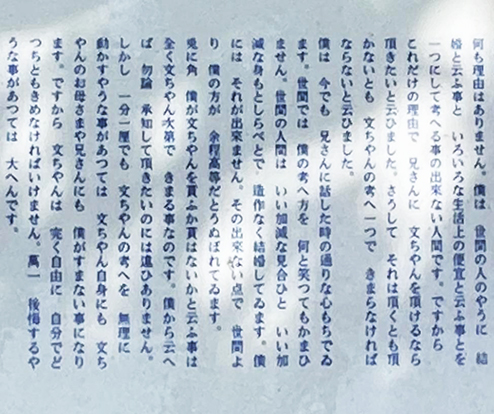

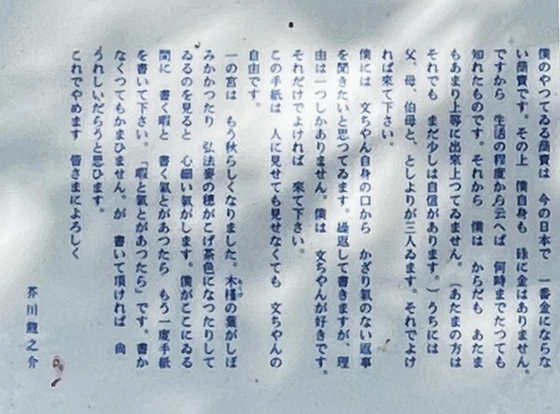

先に芥川龍之介ゆかりの草庵として千葉県九十九里の一宮館に付設された芥川荘を探訪した。実際に訪問してみて、その空気感に触れることで得られる体感は、その小説作品にふれてもいることからより肉声として感じさせられる部分を意識した。作家の空間には数寄を感じる。

そういった「人と住まい」という部分ではさまざまな芸術作家たちの住宅を見て来て、掘り下げて見てみたくなる。そういえば司馬遼太郎さんの記念館に行ったときにも、ガラス越しだけだったけれど、作家の作品作りに随伴していた空気感を味わったことも思い出していた。

そういった流れのなかに札幌、北海道住宅の類縁をたどれば、有島武郎の旧邸がある。有島については現・北海道開拓の村に移築保存された旧邸もあるけれど、有島自身が深く設計にも関与したとされているのがこちらの建物で、新婚当時の1912年8月に、現札幌市北区北12条西3丁目に竣工した。勤務していた北海道大学の正門にほど近い立地ということになる。

いわゆる日本的な伝統的住宅とはかなり隔絶したデザイン感覚であり、とくに新築後早々に塗られたとされる赤褐色ペイントの印象は強烈だったに違いない。北海道開拓では「洋造」がその建築性能追究を目的として導入されたワケだけれど、戸建て住宅のデザイン典型としてもこの有島邸は特徴的。こうした日本伝統とは隔絶したデザイン感覚も、日本人全体に札幌・北海道というものがまさに新天地的なイメージ、意識を盛り上げていったに違いない。

わたしがReplan誌を創刊した当時、活躍していた建築家・倉本龍彦氏の住宅デザイン感覚にもこの有島武郎邸の雰囲気が大きく影響を与えていた。「札幌らしい」というデザインのクラシックとしてわたしたち年代には懐かしさを覚えさせられる。

こちらもメモリアル建築としていまは札幌芸術の森に移築保存されている。

有島は1878年(明治11年)3月4日-1923年(大正12年)6月9日)という45年間の生涯だったけれど、そのうち12年間は札幌で過ごしている。日本社会で北海道、札幌は明治以降の「国際化」のなかで一種特異な象徴的地域になったけれど、そういう札幌のイメージを沈殿させた文学者として有島武郎の存在はきわめて大きかったのだと思う。有島の作品に登場する札幌の街並みなどから刺激された「エキゾチズム」が日本社会に染みわたって行ったと思う。時計台の鐘について作品中で描写する箇所があるけれど、まだ見ぬ津軽海峡の先の民族の新天地への思いは、かれの作品を通して醸成されていった部分も大きいのではないか。

年齢的には芥川の14-5歳年上にあたるけれど、本格的作家活動としては芥川龍之介とほぼ時期が重なっている。芥川のことを書きながら、一方で気になり続けていた有島武郎邸、こっちもちょっとシリーズ的に深掘りしてみたいと思います。

English version⬇

Former Takeo Arishima’s residence, a typical “Sapporo style” design residence-1

Since the Meiji period, encouraging immigration to the cold region of Hokkaido has been a national security issue for Japanese society. The design of the Takeuro Arishima Residence deeply imprinted this image. …

Earlier, we visited Akutagawa-so, a hermitage attached to Ichinomiya-kan in Kujukuri, Chiba Prefecture, as a hermitage associated with Ryunosuke Akutagawa. I was conscious of the fact that the experience I gained by actually visiting the villa and coming into contact with its atmosphere was more like a physical voice from the fact that I was also exposed to the novelist’s works. I feel sukiya in the artist’s space.

I have seen the residences of various artists in terms of “people and their homes,” and I would like to delve deeper and take a look. I remember that when I visited Ryotaro Shiba’s memorial museum, I was able to experience the atmosphere that accompanied the artist as he created his works, although only through the glass.

In the same vein, the former residence of Takehiro Arishima is located in Sapporo, Hokkaido, and is related to the Hokkaido Houses. Arishima’s former residence has been relocated and preserved in the current Hokkaido Kaitakunomura (Hokkaido Development Village), but it is said that Arishima himself was deeply involved in the design of this building, which was completed in August 1912, when he was newly married, in Kita 12-jo Nishi 3-chome, Kita-ku, Sapporo. It is located close to the main gate of Hokkaido University where he worked.

The design sense of the house was quite different from the traditional Japanese style, and the reddish-brown paint, which is said to have been applied early after construction, must have made a particularly strong impression on the owner. The Arishima Residence is unique as a typical example of a detached house design, even though “Western-style construction” was introduced in the Hokkaido frontier to pursue architectural performance. This sense of design, which is so different from traditional Japanese design, must have contributed to the Japanese people’s awareness of Sapporo and Hokkaido as a new land.

The atmosphere of the Tatsuhiko Kuramoto residence had a great influence on the sense of residential design of the architect Tatsuhiko Kuramoto, who was active at the time of the first issue of Replan magazine. It is a classic of “Sapporo style” design that makes us nostalgic for our generation.

This building has been relocated and is now preserved as a memorial building in the Sapporo Art Park.

Arishima lived 45 years (March 4, 1878 – June 9, 1923), 12 of which were spent in Sapporo. Hokkaido and Sapporo became a kind of unique symbolic region in the “internationalization” of Japanese society after the Meiji period. I believe that the “exoticism” stimulated by the streets of Sapporo in Arishima’s works permeated Japanese society. In one of his works, he describes the bells of the clock tower, and I believe that his works may have fostered the desire for a new land beyond the Tsugaru Straits that had yet to be seen by the Japanese people.

Although he is 14-5 years older than Akutagawa in age, his serious writing career coincides with Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s. While writing about Akutagawa, I also wrote about him in his works. While writing about Akutagawa, I would like to delve a little deeper into the residence of Takehiro Arishima, which has been on my mind for some time.

Posted on 10月 16th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »