人間は自分ひとりで生きていける存在ではない。親があってはじめてこの世に生を受け、家族というぬくもりに支えられて成長していくもの。そしてその後「世に出た」後も、その出自の環境からさまざまに支えられながら、人生という波濤のなかに漕ぎ出していくものだろう。わたし自身も自ら顧みて、そうした大きな「繭」のようなものに深く抱かれていたことが実感させられる。この石ノ森章太郎生家を探訪していて、おばあちゃんや実姉の残影が色濃く感じられて、作家の内面を「覗き見た」思いが強い。さまざまな断面からのぞき得たけれど、さらに父親や母親の思いなども掘り起こすことが出来たらと思っている。そしてそのことが身を締め付けるように愛おしいと感じられる。

こういう部分を注目していると柳田國男の掘り起こした民俗、いわば日本人的な「前世」観という思想へのはるかな探究につながるのかも知れない。「作家と住空間」電子本で探究した柳田國男だけれど、わたしはその後も柳田さんの思想痕跡にずっと「抱かれている」と感じている。ただ、柳田さんが生きていた頃から時代は先に進んで、柳田さん以降の日本人の生命の積層があって、独特な「民俗」も多様に展開しているのだと思う。

そういう典型的存在として、わたしの思春期とも大きく重なる石ノ森章太郎の部屋にたどりついてしまった(笑)。そうなんです、ある種「来てしまった」感が盛り上がり、燃えさかっていた。

わたし自身はかれ石ノ森章太郎についてそこまで深い「心的交流」をしていたか、と考えれば、たとえば司馬遼太郎の作品群との対話時間のような近接感には至っていない。・・・と思っていた。しかし、この写真のような光景に出会ってしまったら、一気に自分の中学生頃の感受性世界と深く応答させられてしまったのです。

ちょうど石ノ森章太郎が父親からマンガ家志望に反対されたのと同様に、わたし自身は父親から描いていたマンガ作品を焼却処分されていた。そういう思春期の体験感覚が一気に蘇ってしまった。別に空間としての感じがわたしの過ごしていた部屋と似ているワケではないのに、そういう心理の復元起動力、パワーがこの部屋から感じられた。

作家の住空間として残されている住宅のなかで同時代感が大きくスウィングしてくるのは、わたし自身の年齢から考えてギリギリ石ノ森の世代でしょう。おおよそ14-5年程度の時間差はあるけれど、戦後しばらく経った昭和中期が鮮烈に襲ってきたと感じていたのです。やはり人間と住空間はオモシロい。

English version

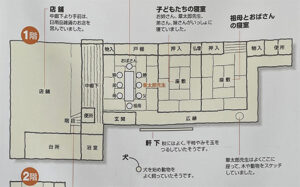

[Aspiring manga artist and adolescent Shotaro Ishinomori’s room

The restorative activation and power of the psyche that the living space has. The feeling of life swinging. The feeling of having ‘arrived’ in such a place. …

Human beings are not beings who can live on their own. He is born into the world only after his parents, and grows up supported by the warmth of his family. After they ‘come into the world’, they are supported in various ways by the environment in which they came from, as they paddle out into the surging waves of life. Looking back on my own life, I realise that I was deeply embraced by such a large ‘cocoon’. When I visited the birthplace of Shotaro Ishinomori, I could feel the strong traces of my grandmother and sister, and I strongly felt that I had ‘peeked’ into the artist’s inner life. I was able to peek into various aspects of the artist’s life, but I hope to be able to further uncover his father’s and mother’s thoughts and feelings. And that makes me feel squeezed and lovely.

Paying attention to these aspects may lead to a far-reaching exploration of the folk customs that Kunio Yanagida unearthed, the Japanese view of ‘prehistoric life’, so to speak. I have been ‘held’ by the traces of Yanagida’s thought ever since my exploration of Kunio Yanagida in the e-book ‘The Writer and the Living Space’. However, since the time when Mr Yanagida lived, times have moved on and there is a layering of Japanese life after Mr Yanagida, and I think that the unique ‘folklore’ has developed in various ways.

As a typical example of such an existence, I ended up in the room of Shotaro Ishinomori, whose adolescence also overlapped greatly with my own (laughs). Yes, a certain sense of ‘I’ve arrived’ was rising and burning.

When I think about whether I myself had such a deep ‘emotional exchange’ with Shotaro Ishinomori, I have not reached the same level of proximity as in the time I spent talking with Ryotaro Shiba’s works, for example. … I thought. However, once I came across a scene like the one in this picture, I was at once made to respond deeply to the world of sensitivity of my junior high school days.

Just as Shotaro Ishinomori was opposed by his father to his aspiration to become a manga artist, I myself had had the manga works I was drawing burnt by my father. The sensation of that kind of adolescent experience came back to me all at once. The room does not resemble the room in which I used to spend my time, but I could feel the power of psychological restoration and activation in this room.

Among the residences that have been preserved as artists’ living spaces, it is probably Ishinomori’s generation, just barely considering my own age, that has the greatest swing in the sense of contemporariness. There is a time gap of about 14-5 years, but I felt that the mid-Showa period, some time after the war, had struck me vividly. After all, people and living spaces are interesting.

Posted on 3月 14th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅取材&ウラ話 | No Comments »