〜綿密な計画を立てて、設計してみた所で、住んでみれば何かと不自由なことが出て来る。・・・作りすぎても、人間が建築に左右されることになり、生まれつきだらしのない私は、そういう窮屈な生活が嫌いなのである。田の字に作ってある農家は、その点都合がいい。いくらでも自由がきくし、いじくり廻せる。ひと口にいえば、自然の野山のように、無駄が多いのである。〜

きのうの続きであります。上の文章はきのうも紹介したのですが、きょうのブログのテーマに強く関わる部分だと思って再掲載。

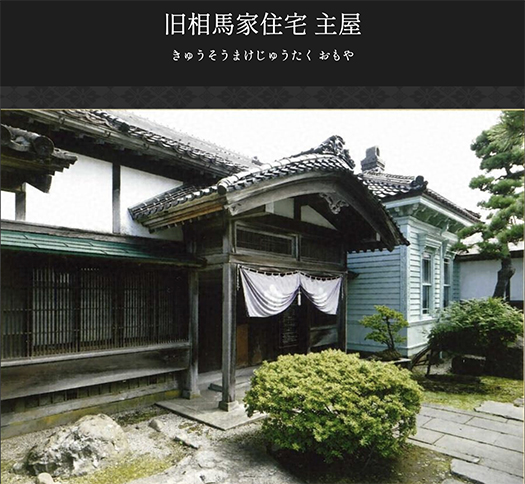

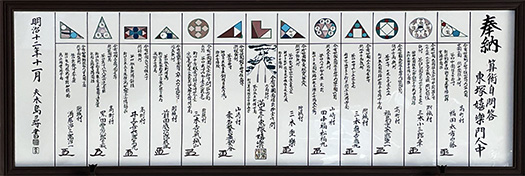

あ、写真はこのちょっと前に書いた兵庫県福崎の「柳田國男生家」の様子の写真です。ご主人の白洲次郎さんは兵庫県出身者だということで、空間の空気感として共有性があるように思う。というか、東京とか京大阪という大都市圏に対しての兵庫県、神奈川県の対置性の共通感だろうか。この文章は白洲次郎・白洲正子のうちのどちらが書いたのかはわからない。

さて本題に戻ると、たぶん文章表現力としては白洲正子さんが書かれたように思うけれど、夫婦の住宅観が非常によく伝わってくる部分。そしてわたし自身も、自分の家とかたくさん取材してきた経験を踏まえても、共感がつよく感じられるのですね。

わたしも仕事上、設計者とか建築の「プロ」のみなさんと交流するのですが、そしてその使われる言語体系も一応は理解できるのですが、やはりホンネではこの白洲さんのコトバに共感する。

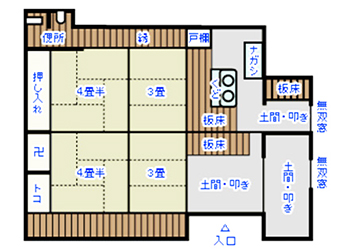

日本人的な暮らし方についての血肉になっている「自由度」をわかりやすく言語化していると思うのです。田の字型の間取り、いかにも融通無碍な規格性が日本人に無限の「自分ちなんだから、自由に使う」といういわば「内心の自由」にも似た原初性を感じさせられる。

どう使おうがこっちの勝手だという自由解放宣言のような気分を強く感じる。日本の伝統的家屋を見る度に、こういう規格性こそが日本の暮らし方の哲学を生んできたのではないかと思うのです。

家を木材で構成する様式が標準になる社会において、その規格寸法にすなおに準拠して作って行けば、おのずと田の字型という間取りの合理性に至る。日本人はながくそういう空間で「生まれ,育ち、死んで」いったのでしょう。そういう人間の叫び声がこだましてくる。

そういう日本的な住宅構造とそこで繰り返されてきたいとなみの奥行きが、つよく迫ってくる。

English version⬇

The “Sei-katsu-sha” Perspective on the House

If you construct a house with lumber of the planned dimensions, you will naturally end up with a “tano-ji” shape. This is a truly Japanese standard. This standardization gave freedom to the Japanese way of living. The Japanese way of living

〜Even after careful planning and designing, you will find that there will be some inconveniences when you live in the house. If you build too much, you are subject to the architecture, and I, who am not a sloppy person by nature, do not like such a cramped life. A farmhouse built in the shape of a rice paddy is convenient in this respect. I can have as much freedom as I want, and I can tinker around as much as I want. In a word, there is a lot of waste, just like a natural field. 〜The following is a continuation of yesterday’s article.

This is a continuation of yesterday’s article. The above text was written yesterday as well, but I thought it was strongly related to the theme of today’s blog, so I republished it again.

The photo is a picture of the “Yanagida Kunio Birthplace” in Fukusaki, Hyogo Prefecture, which I wrote about a little while ago. The owner, Jiro Shirasu, is a native of Hyogo Prefecture, and I think there is a commonality in the atmosphere of the space. Or perhaps it is the common sense of counterpoint of Hyogo and Kanagawa prefectures to the metropolitan areas of Tokyo and Kyoto-Osaka. I am not sure which of Jiro Shirasu or Masako Shirasu wrote this text.

Returning to the main topic, I think that Masako Shirasu probably wrote the text in terms of expressive power, but it is the part that conveys the couple’s views on housing very well. And, based on my own experience of having interviewed many people about their own houses, I can feel a great deal of empathy for them.

In my work, I interact with designers and architectural “professionals,” and I can understand the language system they use, but I really feel empathy for Mr. Shirasu’s words.

I think that he has clearly articulated the “degree of freedom” that is part of the Japanese way of life. The tano-shaped floor plan, with its flexible and unrestricted standardization, gives the Japanese a sense of primordial freedom, a kind of “inner freedom,” as if to say, “It’s my house, so I can use it as I please.

I feel a strong sense of a declaration of freedom and liberation, as if to say, “It’s my house, so I’m free to use it however I want. Whenever I see a traditional Japanese house, I think that this kind of standardization is what has given birth to the philosophy of the Japanese way of life.

In a society where the standard house style is to be made of wood, if one follows the standard dimensions, one will naturally arrive at the rationality of the tano-shaped floor plan. Japanese people were “born, raised, and died” in such spaces for a long time. Such cries of human beings echo in the house.

The depth of the Japanese residential structure and the repeated patterns of the house are very powerful.

Posted on 11月 21st, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング | No Comments »