絵というのは人間にとって、コトバ以上に本然的なコミュニケーションツール。アルタミラとかラスコーとかの洞窟絵画は低酸素状態になりやすい洞窟で絵を描くことで、意識混濁、もうろうとした心的状態になることを、むしろ意図的に自らを追い込んで、よりスピリチュアルな表現を目指したと言われている。また、その目的として天体の運行などの自然科学的探究を表現したとも言われている。美術の歴史とはそういう精神の結界、宗教的な空間にごく自然に蓄積されてきたことは自明。

北海道島でも積丹半島の手宮などで洞窟絵画が人類痕跡として遺されている。見学するときにはそういう空気感がオーラとして自分を包んでくれているように感じられる。そういう体感が好きです。

本州でも各所にそういった絵画空間はあるけれど、建築空間に宗教が集約されていって、奉納画というようなジャンル形式が成立していったのでしょう。きのう紹介したアマテラスの絵なども画題としてけっこう多いそうで、最近建てられた神社では、アニメ顔のカワイイ系のアマテラス画像なども奉納されているという。まことに「世に連れ」というごく身近な表現形式といえるのでしょう。

撮影してきた英賀神社の掲額画の表現テーマは比較的に武者絵の類が数としては多い。日本史がはじまって以来、継続してきた戦争は民人の人生・生き様に直接的にかかわり、そのぶん強い興味が働いてきたに相違ない。現代でこそ「政経」は分離しているけれど、歴史的には一体のものであって、現世でのひとの運命に大きな影響をもたらせてきたことを表しているのでしょう。

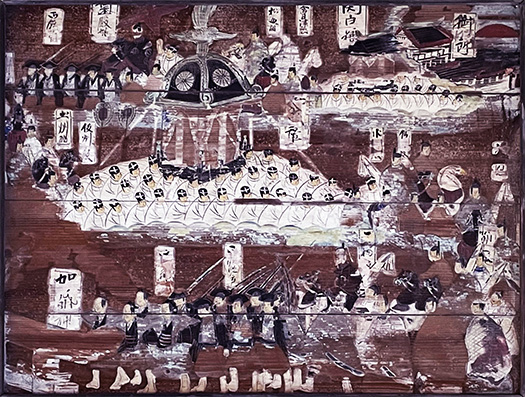

上に挙げた絵は、年代不詳だけれど、画題を見ているとどうも天皇の行幸風景かと。屋根の上に皇位を示す鳳凰の像が立っている鳳輦(ほうれん)と呼ばれる乗り物が画面中央に描かれている。白衣を着た多くの人間によって「神輿」のように持ち上げられている。

その後方には「関白」という文字も見えるので、天皇に供奉していることを表現したのか。さらに先導するように武家が描かれているので、年代的には江戸期の典型的な社会権威体系を表していると思える。この姫路市英賀の周辺に天皇の行幸があった記録であるのか、単なる創作であったのか不明。

その下の2枚に分けた絵は、「縣社英賀神社祭典の図」と題された画題。縣社というのは神社の社格を表していて、官・国幣社より下、郷社(ごうしゃ)より上で、県から奉幣した神社とされるけれど、神輿をたくさんの裸形の人びとが威勢よく担ぎ上げている勇壮な図柄。角村ごとの名前が神輿に付けられているので、この英賀神社周辺の人びとがムラ同士の競争意識に駆り立てられるという日本的な民俗をよく伝えてくれている。

願主としては「付城村」で明治31年という年代。ちなみに付城という地名はいまの「英賀保」駅のすぐ近くに確認できる。英賀神社にもほど近い。

民俗のありようがさまざまに想像されてくる。時間を超えて民人と対話できる機縁ですね。

English version⬇

Aga Shrine -4- “Folk” Consciousness Revealed in Dedication Painting

The emperor’s visit and the competitive festivals held by each mura (village) for local deities. The kitschy expression of the votive picture is fragrant with the base of Japanese sentiment. ・・・・.

Painting is a more natural communication tool for human beings than words. It is said that cave paintings such as those in Altamira and Lascaux were created in caves where people were prone to hypoxic conditions, and that the painters intentionally pushed themselves into a state of mental confusion and stupor in order to achieve a more spiritual expression. It is also said that the artist’s goal was to express natural scientific explorations such as the operation of the heavenly bodies. It is obvious that the history of art has accumulated quite naturally in such spiritual and religious spaces.

On the island of Hokkaido, cave paintings have been left behind as traces of mankind in places such as Temiya on the Shakotan Peninsula. When I visit, I feel as if such atmosphere surrounds me as an aura. I like that kind of experience.

In Honshu, too, there are such paintings in various places, but it is likely that religion was concentrated in architectural spaces and a genre form such as votive paintings was established. The picture of Amaterasu introduced yesterday is said to be one of the most common subjects of votive pictures, and at a recently built shrine, a kawaii image of Amaterasu with an anime face is also dedicated. It is truly a very familiar form of expression that “brings us into the world.

The themes of expression in the Eiga Shrine’s hanging paintings that I have photographed are comparatively numerous in the form of warrior paintings. Since the beginning of Japanese history, wars have been directly related to the lives and lifestyles of the people, which must have been the reason for their strong interest in war. Although “politics and economics” are separated today, historically they are one and the same and have had a great influence on people’s destiny in this world.

The above painting is undated, but the title suggests that it is a scene of an emperor on his way to the capital. In the center of the painting is a palanquin with a phoenix on its roof, signifying the imperial throne. It is being lifted up like a “portable shrine” by many people dressed in white.

The word “Kanpaku” can be seen in the back of the palanquin, perhaps representing the fact that the palanquin is being offered to the emperor. Furthermore, since a samurai family is depicted leading the way, it seems to represent a typical social authority system of the Edo period in terms of chronology. It is unclear whether this is a record of an emperor’s visit to the area around Eiga, Himeji, or whether it was simply a creation.

The painting below it, divided into two sheets, is titled “Agata-sha Eiga Shrine Ritual. The picture is a gallant depiction of a portable shrine being carried by a large number of naked people in a vigorous manner. The name of each Kakumura (village) is attached to the mikoshi, which conveys the Japanese folklore that the people around the Eiga Shrine are driven by a sense of competition among the villages.

The name of the petitioner is “Tsukijo Village” and it dates from the 31st year of Meiji. The name “Tsukishiro” can be found near the current “Eikaho” station. It is also close to Eiga Shrine.

The presence of folk customs can be imagined in a variety of ways. It is an opportunity to communicate with the people beyond time.

Posted on 11月 13th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.