各地ごとの神社仏閣などにはその地の歴史性を教えられるということで努めて参詣することにしている。日本社会ではこういう「地の神」への崇敬心が強く伝承されてきていると思う。欧米のようにキリスト教の一神教社会とはまったく異質な「八百万の地神」への民族の思いを実感することができる。

そういうなかでもこの英賀神社には、自身のルーツに多少縁が感じられるということを別にしてもそれがきわめて濃厚に保存蓄積されているように思える。

今回の令和の大修復工事でも、もっともキモの工事として「拝殿」がクライマックス建築として重視され、あらたに再生された空間でも、歴世の「奉納画」がそれこそ満艦飾で掲額されている様子は壮観。

博物館とか美術館とかの文化がなかった時代、これだけの民俗が継続してきたことそのものに驚かされる。今回訪問では夜中に宿泊ホテルを出て、早朝から参拝できたので、じっくりとその掲額を記録することができた。わたしが確認した掲額類は全60枚以上。

先日記述した兵庫県福崎町の三木家住宅では、地域の情報センターとして民俗学者・柳田國男を揺籃させたことにも触れたけれど、この英賀神社もきわめて血脈的類縁性が高い存在ということができる。氏子という民衆主導のカタチでの根深い民俗性を感受することができる。

奉納掲額の画題テーマはわかりやすい民族の歴史浪漫ものが多い。上の画面はアマテラスが天岩戸にかくれてしまったときにアメノウズメが舞い踊ってそれを多くの神々がはやし立てて盛り上がっていたので、ついアマテラスが岩戸をすこし開けた瞬間を捉えて、天之手力男神(アメノタヂカラオ)が岩戸を閉めさせなかった、広く知られた神話のワンシーン。民人にとっての一種のアジール(「自由領域」「避難所」「無縁所」などとも呼ばれる特殊な民俗的エリア)として機能していたことが伝わってくる。祭礼の時などでこの「公共空間」を訪れた親子が、この絵を見ながら会話する様子を想像すると、大衆に根ざした日本独特の伝統文化と実感できる。

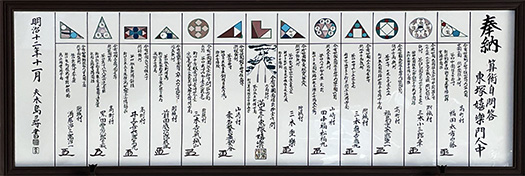

こういう奉納画はこの神社をながく支えてきた地域の「氏子衆」が作ってきた民俗伝統。掲額のなかには年代を表記したものもあるけれど、すでにかなり落剥しているような古格なものには判然としないものが多い。上の奉納記録は「明治12年11月」と明確な記述がある。たいへんキレイな保存のこれでも1879年だからすでに144年経過している。古格なものはさてどれくらい年代を遡れるか、調査が行われることを期待したい。

氏子の記名、全13人の中には「三木」姓が4人確認できる。また、司馬遼太郎さんの本姓「福田」名も1名確認できる。こういう「伝統文化」の世界から大きくスピンアウトした北海道人としては、目眩がするほどの時間の積層ぶりにワクワクさせられるのですね。この「掲額」類、あしたもご紹介します。

English version⬇

Folk Drama Unfolds in Dedicated “Hanging” Paintings Eiga Shrine-3

The upper part of the worship space with no walls is decorated with a full array of hanging paintings. A symbolic scene of a Japanese “folk” tale. Manga-like clarity. Manga-like clarity.

I make an effort to visit shrines and temples in each region, as they teach me about the history of the area. I believe that in Japanese society, this reverence for “local deities” has been strongly handed down from generation to generation. It is a very different feeling from the Christian monotheistic society of Europe and the United States, where the people have a strong sense of respect for “all the gods of the earth.

Even if we do not consider the Eiga Shrine to have some connection to our own roots, it seems to have preserved and accumulated a very strong sense of this belief.

In the major restoration of the shrine in 2025, the “hall of worship” was the most important part of the restoration work, and the newly restored space is spectacularly decorated with “votive paintings” from the past generations.

It is amazing to see how much folklore has continued in the absence of museums and art galleries. Since I was able to leave my hotel in the middle of the night and visit the shrine early in the morning, I was able to take my time and record the display. I checked more than 60 plaques in all.

As I mentioned the other day, the Miki family residence in Fukusaki-cho, Hyogo Prefecture, was the cradle of folklorist Kunio Yanagida as a local information center, and this Eiga Shrine is also highly related to the Miki family. The Eiga Shrine, too, is highly related to the local community.

Many of the themes of the votive plaques are easy-to-understand ethnic historical romances. When Amaterasu was hiding behind Ama-no-Iwato, Amenouzume was dancing and many gods were excitedly cheering her up. A scene from a well-known myth. The scene conveys the fact that this place functioned as a kind of azir (a special folkloric area also called “free territory,” “refuge,” or “place of no ties”) for the people of the area. Imagining parents and children visiting this “public space” during festivals and other occasions and conversing with each other while looking at this painting, one can feel that this is a uniquely Japanese traditional culture rooted in the masses.

These votive pictures are a folk tradition created by the local “Ujikoshu” who have supported this shrine for a long time. Some of the plaques are dated, but many of the older ones, which seem to have already fallen off, are not clearly identified. The dedication record above clearly states “November, 1879. Even this very well-preserved one was made in 1879, so 144 years have already passed. We hope that an investigation will be conducted to see how far back in time the oldest items can be traced.

Among the 13 names of the shrine’s clergymen, four are identified as having the surname “Miki. We can also confirm that one person is named “Fukuda,” the real family name of Ryotaro Shiba. As a Hokkaido native who has largely spun out of the world of “traditional culture” like this, I am thrilled by the dizzying layering of time. I will introduce these “hoist plaques” and others tomorrow.

Posted on 11月 12th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.