先日来「食卓テーブル」のことが気になっているのですが、歴史的には日本人の元々の食卓習慣は、「銘々膳」というのが基本ということに気付かされる。

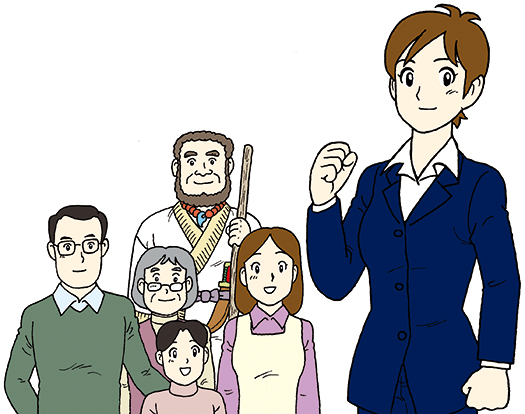

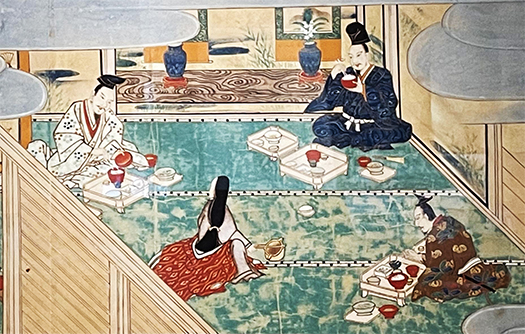

写真は松山市の「湯築城資料館」でみかけた武家の食事風景。まぁ「エラい人」の食事風景で、床の間近くの席に座るいちばんの「貴人」と相伴にあずかっている2人が食事して、それを女性がいちいちの「上げ膳据え膳」に気遣っている様子がわかる。

こういう食事が一般的であって、こういった風景からは身分制度をそのまま表現し、そしてそうした「格式」意識を食事の度ごとに教育し、再確認させるような機会として考えていたようだ。いやはや面倒くさいと考えるのが一般的だろうと思う。たしかに支配階級としてはこういった格式最重視だっただろうけれど、より一般的には「囲炉裏」を囲んだような食事習慣があって、その席次について家の当主と家族関係が表現されたりはしても、基本的には囲炉裏の火を囲んで対話するような形式だったと考える方が普通だろう。

絵のような食事風景は、いかに支配者の権威が貫徹しているのか、それを誇らしやかに誇示している。

実質はかなり希薄化していっただろうけれど、一応タテマエとしての社会性習慣化といったようなことだったのだろうかと思える。

しかし、個人別の「銘々膳」であること自体は囲炉裏を囲む食卓でも、同様だったとされる。その除外例としては「ナベ料理」があったのだろう。よく「無礼講」というコトバがあるけれど、あれも格式としての社会規範強制に対して「そう言うのはナシ」という日本人的「開放感」表現なのではないか。

それにしても給仕している女性はたいへんな「気遣い重労働」。

「粗相がないように、ご満足いただけるように」と目配りさせられていたのだろう。

こういうのが日本の「格式主義」の源泉として相当長期にわたって日本人の精神文化を規定してきただろうことが容易に思い浮かんでくる。

で、こうした「銘々膳」格式スタイルは、戦後の公団住宅ライフスタイルの導入とともに「大テーブル食」スタイルに変貌していくことになるのでしょう。生活合理主義という側面から考えれば、いま進行している流れはきわめて自然だし、現代の「夫婦共稼ぎ」が一般化したライフスタイルのなかでは、より時間節約型になっていく趨勢は強まっていくだろう。また、食事つくりという家事労働も、夫もいつでも作る立場になれる、という生活スタイルになっていくことだろう。

そのうちこういった絵を見て「なにやっているところだろう?」みたいな常識変換がやがて起こってくるかも知れない(笑)。さて。

English version⬇

Japanese dining table – “Meizuzen” dining scene

A social culture that enforces the role of the woman who cares for the “master” of the highest rank. This kind of scene will continue to become a “marginal custom” in the future. …

I have been thinking about “dining table” since the other day, and I am reminded that historically, the original dining custom of the Japanese people was based on the “meishizensen” style of dining.

The photo shows the dining scene of a samurai family seen at the “Yuzuki Castle Museum” in Matsuyama City. It is a dining scene of “important persons,” and you can see the most “noble person” sitting near the alcove and his two companions eating, and the women taking care of each and every meal.

This kind of meal was common, and it seems that this kind of scene expressed the status system as it was, and was considered as an opportunity to educate and reaffirm the awareness of such “prestige” at each meal. I think most people would consider this a hassle. The ruling class may have placed the utmost importance on such formalities, but it is more common to think of the meal as being held around a “sunken hearth,” and although the seating arrangements may express the relationship between the head of the family and the family members, it is more likely that the basic format of the meal was a dialogue around the fire.

The picturesque dining scene proudly flaunts how the authority of the ruler was penetrated.

Although the substance of the meal may have been diluted considerably, it may have been a kind of social habitualization as a form of formalization.

However, it is said that the same was true at the dining table around the sunken hearth. An example of an exception to this rule would have been “nabe ryori. The word “murekou” is often used to describe the Japanese sense of “openness” in contrast to the social norm of “no such thing” that is enforced as a formality.

The women who serve the guests are performing hard labor, and they have to be very careful.

They must have been paying close attention to ensure that there would be no mishaps and that the guests would be satisfied with their meal.

It is easy to imagine that this kind of “formalism” has been the source of Japanese spiritual culture for a long period of time.

This “meizentei” style of formalism would be transformed into a “big table meal” style with the introduction of the public housing lifestyle in the postwar period. From the standpoint of lifestyle rationalism, the current trend is quite natural, and the trend toward time-saving is likely to intensify in today’s lifestyle where dual-income couples have become the norm. In addition, the lifestyle will become one in which husbands can be in the position of cooking meals at any time.

Eventually, people will look at a picture like this and say, “What is she doing? (laugh). Now, let’s see what happens next.

Posted on 3月 8th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »