きのう見たように、幕末明治初頭の日本に対して、欧米の市場経済が期待したものは養蚕業による絹製品群だった。近代国家として独立を確保しさらに欧米列強と伍して行くためには、当然ながら「国力」の涵養が第一に必要。国内戦争を経て権力体制の樹立に成功して後、それまでの幕府が尽力してきた経済的な努力を明治政府はまっとうに継承し、発展させていった。

それまでの日本社会でも養蚕業は環境的適地性があって全国で展開されていたが、それは農家の女性たちによる「家内制手工業」の枠に留まっていた。そういう状況の中でフランスなどの大消費地からの需要が急拡大したことで、粗悪品などが流通する結果になってしまった。そうしたなかで主にフランス式の発展した「大規模工場生産方式」が志向された。そのプロセスでは、初代の指導者、仏人ポール・ブリュナは、日本の家内制手工業の養蚕技術を詳細に研究して、日本人女性たちの手法に学びながらそのエキスを反映した工場生産方法に昇華させていったとされる。

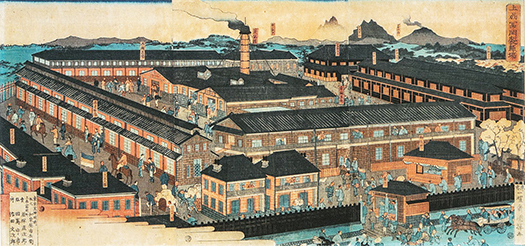

明治5年にこの富岡製糸場からの製品出荷が開始されて、その均質で高精度な絹製品は、欧米市場で高い評価を獲得していくことになる。

こうしたプロセスで国営として製糸場は経営されていくけれど、最初期には女性たちの「募集」に大きな困難があったと言われる。「異様な西洋人たちによって工女はその生き血を吸われる」というような風説が広がって、募集活動は壁にぶち当たったのだ。〜御雇いの異人どもは、実は魔法使いの悪鬼輩にして、彼のおふれに応じた年若の工女を入れるや、可愛や其女等はかれらに生き血を絞られていのちを断たれてしまう(当時の庶民の発言:富岡製糸場誌より)〜

そういう状況に対して設立に尽力して所長となる尾高惇忠は自ら範を示すため、娘の「勇」を伝習工女第1号として入場させてウワサの払拭を図ったのだという。官営工場として、ここで最新の工場生産手法を学んで、地元で設立される予定の製糸場にその技術を持ち帰るというまことに崇高な使命感を訴求して、武家の娘たちを中心にして、徐々に工女は確保されていったのだという。

鉄道がようやく新橋〜横浜間で開通したばかりの当時、この群馬の富岡には全国30道府県からやってきた彼女たちは、徒歩でやってきたのだ。それも交通宿泊費はすべて自費だったのだという。

国を思い郷里の発展を思い、風説におびえながらも献身した彼女たちの状況を不覚にも初めて知った。

ふっと『元始、女性は太陽であった』という女性解放運動の先駆者として知られる作家、平塚らいてうの言葉が思い出された。神々しく感じられる伝習工女たちの表情から、女神・アマテラスの残照を見る思い。

English version⬇

Women were the sun even in the Meiji era.

The phrase “In the beginning, women were the sun” reverberates loudly. The goddess Amaterasu is the basis of Japanese culture. The divine expressions of the women who were responsible for the national economy of the Meiji era. The sun, the sun, the sun, the sun, the sun.

As we saw yesterday, what the Western market economy expected from Japan at the end of the Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji period was silk products produced by sericulture. In order to secure independence as a modern nation and to compete with the Western powers, the cultivation of “national power” was naturally the first priority. After succeeding in establishing a system of power through domestic wars, the Meiji government properly inherited and developed the economic efforts of the previous shogunate.

Until then, sericultural industry had been developed throughout Japan because of its environmental suitability, but it remained within the framework of a “cottage industry” operated by farm women. Under such circumstances, demand from France and other large consumption centers increased rapidly, resulting in the distribution of inferior products. Under such circumstances, the “large-scale factory production system,” which was mainly developed in the French style, was oriented. In the process, the first leader, Frenchman Paul Brunat, is said to have studied in detail the sericultural techniques of the Japanese cottage industry and sublimated them into a factory production method that reflected the extracts while learning from the methods of Japanese women.

In 1872, the Tomioka Silk Mill began to ship products, and its homogeneous and highly precise silk products won high acclaim in the European and American markets.

Although the silk mill was managed as a state-owned enterprise through this process, it is said that there was a great difficulty in “recruiting” women in the early stage of the operation. The recruitment process ran into a wall due to the spread of rumors that the women would be “sucked alive by strange Westerners. 〜The hired foreigners were actually evil wizards, and as soon as they let in young workers at his behest, they squeezed the lifeblood out of the girls and cut off their lives (from a commoner’s comment at the time: “Tomioka Silk Mill Magazine”).

Junchu Otaka, who worked hard for the establishment of the mill and became its director, tried to dispel the rumors by admitting his daughter, “Isamu,” as the first apprentice. The factory was run by the government, and the girls, mainly daughters of samurai families, were gradually recruited, appealing to the noble mission of learning the latest factory production techniques and bringing them back to the local silk mill to be established in the area.

At a time when the railroad had just opened between Shimbashi and Yokohama, women from 30 prefectures in Japan came to Tomioka, Gunma, on foot. They had to pay for their own transportation and lodging.

I was surprised to learn for the first time of their devotion to their country and to the development of their hometown, even though they were frightened by rumors.

I suddenly recalled the words of Raiteu Hiratsuka, a writer known as a pioneer of the women’s liberation movement, who said, “In the beginning, women were the sun. The godlike expressions on the faces of the apprentice workers reminded me of the afterglow of the goddess Amaterasu.

Posted on 10月 9th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.