国立歴史民俗博物館での旧石器・縄文・弥生・古代までの展示大革新。

その興奮の余韻冷めやらず都合60回もブログを書き連ねてきた。通常の「住宅ブログ」テーマからはかなり飛躍かも知れませんが、住宅取材していると必然的に現代人の「生き方・暮らし方」という根源的テーマから目を背けるわけに行かない。いわば「こころのありよう」という領域では歴史が教えてくれる人びとの生き様にルーツを辿りたくなる。ということですが、途中何回か建築の根源的テーマにも触れてきた。本日は日本列島史のなかで画期になった仏教伝来と、寺院建築文化ということを探ってみたい。

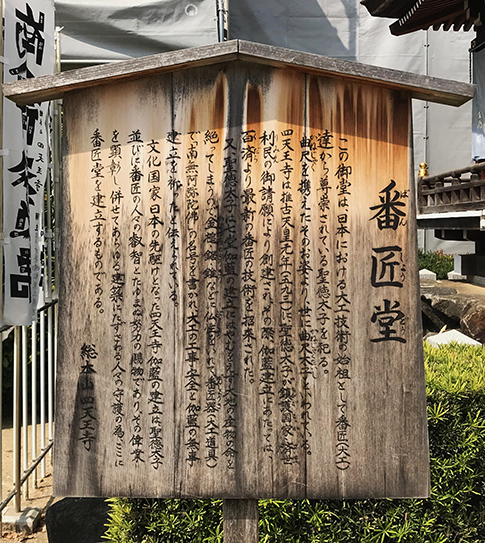

上の写真は大阪四天王寺の南大門から、正面に仁王門・五重塔を見た外観と、五重塔裏手に静かに建っている「番匠堂」のなかに端座されている聖徳太子のお姿像。太子はなんと差し金・曲げ尺を手に持たれている。番匠というのは大工職という意味であり聖徳太子は日本の大工職にとっての最高の守護神とでもいえる存在なのだ。

そういう伝承をいまも大切に守って四天王寺創建に当たって半島から先進木工技術を伝えた日本最古の「工務店組織」金剛組が幟にその名を記している。それまで農業土木技術の進化形ということで古墳造営が最大の「宗教的象徴」であったものが、仏教という新宗教にすべて置換されて、四天王寺・飛鳥寺・法隆寺と国家プロジェクト仏教建築が世を覆っていく。

古墳の造営はいろいろに推理されるけれど、しかしある時期にまったく造営されなくなるということにむしろ強い必然性を感じる。仏教導入と同時に寺院建築という当時の社会に取ってみたら驚天動地の「建築的技術革新」が一気に舶来してきたということなのでしょう。もちろん藤原京などの王宮建築は先端的に出現したけれど、それ以上に宗教施設として衆生にも開放される建築空間、その文化に庶民は度肝を抜かれたに違いない。古墳には衆生救済というような側面はなくたぶん支配権力の象徴という側面が強い強制的「宗教」だったと思える。それに対して仏教は来世に向かって救済されるという福音的な香りを感じさせたに違いない。そして建築では見たこともない五重塔のような高層建築もあって日本人にわかりやすく現世救済思想を可視化してくれた。

曲げ尺を持った聖徳太子というのは、まことに象徴的。というのは最新の建築工学・技術が四天王寺などで全面開花して日本の建築技術は飛躍的な発展を見せたに違いないのだ。ときの最高為政者が自らこの最先端技術の先導者でもあったのだろう。現在で言えばIT産業の育成者・未来先導者が政治改革も引っ張っていた、みたいに思われる。

この四天王寺・法隆寺で実質が始まった日本の先端的木造建築技術は、今日、東アジア世界の中核を形成している。繰り返し独裁権力による排仏運動が起こった大陸国家では伝統的木造技術が文化破壊され、木造技術者たちは日本に支援を求め日本もそれに応えてきている。太子の産業育成の努力が今日に至る日本の技術基盤を形成したと言えるだろう。

長かったブログ連載「列島37,000年史」シリーズは今回で中締め。でもまだ書き残しもあるので、ゲリラ的にやるかも知れません。それまでしばし連載小休止。悪しからず。あ、ブログは年中無休で継続します、よろしく。

English version⬇

The Great Religious Transformation from Kofun “Civil Engineering” to Buddhist “Architecture” (The 37,000 Year History of the Archipelago, Vol. 60)

The construction of Shitennoji Temple and Horyuji Temple was a national project that allowed the people of Asuka and Hakuho to visualize the world of cutting-edge technology. …

The exhibition at the National Museum of Japanese History was a great innovation, covering Paleolithic, Jomon, Yayoi, and Ancient times.

I have conveniently written 60 blogs in the aftermath of that excitement. This may be quite a leap from the usual theme of a “housing blog,” but when you are covering housing, you inevitably cannot turn your eyes away from the fundamental theme of the “way of life and living” of modern people. In the area of “the state of mind,” as it were, we are tempted to trace our roots back to what history has taught us about people’s way of life. This means that I have touched on the fundamental theme of architecture several times along the way. Today, I would like to explore the introduction of Buddhism and temple architecture culture, which was a landmark period in the history of the Japanese archipelago.

The photo above shows the exterior of Shitennoji Temple, Osaka, from the Nandaimon gate looking toward the Nioimon gate and the five-story pagoda, and a statue of Prince Shotoku seated in the “Banshodo” quietly standing behind the five-story pagoda. The statue of Prince Shotoku is seated in the Banshakudo, which stands quietly behind the five-story pagoda. The word “bansho” means “carpenter,” and Prince Shotoku is the supreme guardian deity of carpentry in Japan.

The Kongo-gumi, Japan’s oldest “construction company” that introduced advanced woodworking techniques from the Peninsula to build Shitennoji Temple, still holds this tradition in high regard, and its name is written on a banner. The construction of ancient tombs, which until then had been the greatest “religious symbol” as an evolution of agricultural and civil engineering technology, was replaced by the new religion of Buddhism, and the world was covered with state projects of Buddhist architecture such as Shitennoji, Asuka, and Horyu-ji temples.

The construction of kofun tumuli has been theorized in various ways, but the fact that they ceased to be built at all at a certain point in time seems rather strong and inevitable. This may be due to the introduction of Buddhism and the simultaneous importation of temple architecture, an astonishing “architectural innovation” for the society of the time. Of course, the royal palace architecture of the Fujiwara-kyo Capital was at the forefront, but the common people must have been even more astonished by the architectural space and culture that was open to sentient beings as a religious facility. Kofun tombs did not have the aspect of salvation for sentient beings, but were probably a forced “religion” with a strong symbolic aspect of ruling power. Buddhism, on the other hand, must have had the evangelical flavor of salvation toward the next life. In terms of architecture, Buddhism, with its five-story pagodas and other skyscrapers that the Japanese had never seen before, made the idea of salvation in this life visible and easy for the Japanese people to understand.

Prince Shotoku with a bending scale is truly symbolic. The latest architectural engineering and technology must have flourished at the Shitennoji Temple and other such structures, and Japanese architectural technology must have made great strides forward. It is likely that the highest political leader of the time was himself a pioneer of this cutting-edge technology. In today’s terms, it would be as if the IT industry’s nurturers and future leaders were also leading the way in political reforms.

Japan’s cutting-edge wooden architectural technology, which began with the Shitennoji and Horyuji temples, today forms the core of the East Asian world. As traditional wooden construction techniques were repeatedly destroyed in continental countries by dictatorial movements to eliminate Buddhist monuments, woodworkers turned to Japan for assistance, and Japan responded. It can be said that Taishi’s efforts to foster the industry formed the technological foundation of Japan up to the present day.

Posted on 1月 6th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.