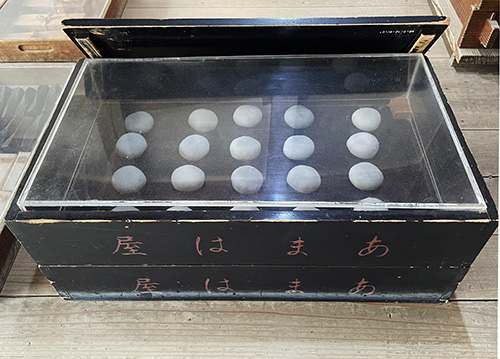

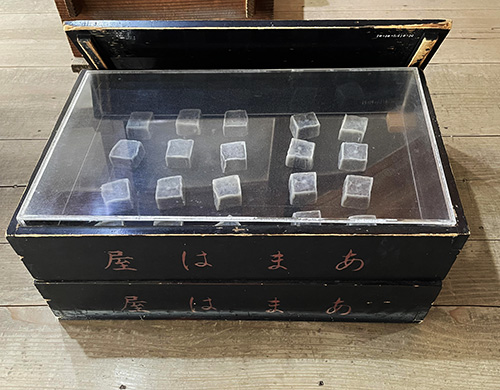

さてこの房総のむらでもいちばん魂を揺さぶられる江戸文化の精緻の町家店舗。「本・瓦版」の店・葛飾堂のご紹介であります。わたしどもの主領域・出版は江戸の浮世絵文化の大興隆、大衆文化大革命を見ずには語ることができないと思う。出版に主要な人生時間を費やしてきた人間として、町家建築としてこういう業態の店舗を参観できる機会に恵まれて心躍る思いがした。

出版、それも木版印刷の歴史について、京都の先達「竹笹堂」さんのHPから要旨引用。

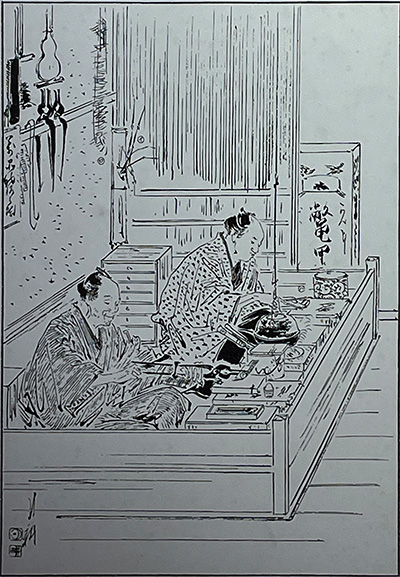

〜戦国の世を家康が統一し泰平が訪れ文化の中心が町民に移行した江戸時代。初頭に京都で商業的な出版が行われ本を取り扱う「本屋」が誕生した。瞬く間に市中に数多くの本屋が並び、続いて大阪に本屋が登場して上方で出版文化が育まれていった。寛永(1624-1645年)には江戸でも本屋が開業。のちに美人画の名手喜多川歌麿や、役者絵の奇才東洲斎写楽などの錦絵を出版して一大版元となる蔦屋重三郎も吉原に書店を構えた。〜

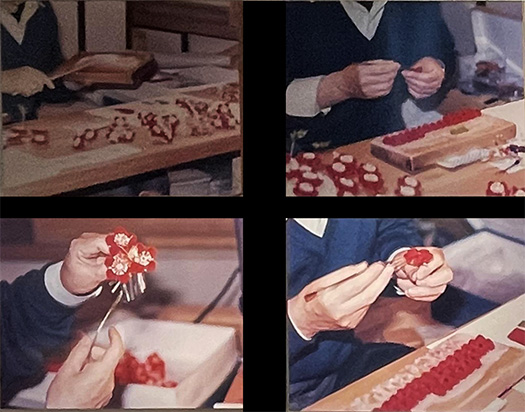

〜伝統木版画技法の確立 大量印刷物を限られた時間と費用で生産するため無駄をそぎ落とし、表現方法をシンプルにすることで浮世絵木版画独特の構図の妙や色彩表現が生まれた。制作工程を分化させ、下絵を描く「絵師」、版を彫る「彫師」、色を摺る「摺師」、それぞれ専門職として作業する三者分業制印刷が確立した。一般に知られる葛飾北斎や喜多川歌麿は絵師で大手版元のお抱えや独立して活動した。素材や色彩、表現全てが独自性に富んだ日本の木版多色カラー印刷は、当時世界最高峰の技法。のちにゴッホをはじめとする多くの芸術家たちに影響を与え世界中を驚愕させた。【豆知識】世界に日本の高度な木版印刷技術が知られたのは、印刷に失敗した木版画を陶器や磁器などの他の輸出品の緩衝材として海を渡ったからだという。〜

いやはや、紙くずとして梱包材に浮世絵を使ったというさりげない事実から江戸期社会の大衆芸術の浸透ぶりに驚かされる。宗教芸術や貴族層の趣味生活に奉仕させられる存在であったヨーロッパ芸術に対して、無造作に紙くずとして利用された木版印刷ニッポン芸術が、まさに文明的驚愕をもたらせたことは日本人として誇らしい。けっして豊かではない都市住民の生活の中で、それでも多色印刷の絵画が各家庭に飾られて、夕餉の一家団欒に話題を提供していたのだろう。その絵画のテーマに則して旅の話題であったり、有名歌舞伎スターのゴシップであったり(笑)、大いに平和な家庭のいっときを彩っていた。もちろん識字率の高さから活字本で学習・情報収集にも余念がなかっただろうけれど、多色印刷のわかりやすさは、ひとのこころに強烈なインパクトを与え続けた。わたし自身はテレビという映像文化に染まった最初期世代だけれど、この江戸期の浮世絵文化にはじめて触れた人びとも、どうも似たような文化革命体験世代だったのではないだろうか。この空気感が愛おしい。

English version⬇

Ukiyo-e Civilization that Astonished the World -1 Edo Period, Boso Townhouse-10

Europeans were horrified by the culture shock of Ukiyo-e paintings being used as packaging cushioning material (laugh). Nippon, a society leading the popularization of art. …

The most soul-stirring store in the village of Boso is a machiya store that is an exquisite example of Edo culture. I would like to introduce Katsushikado, a “book and tile edition” store. Our main area of business, publishing, cannot be described without referring to the great rise of Ukiyo-e culture in Edo, the great revolution in popular culture. As someone who has spent a major part of my life in publishing, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to visit this type of store, built as a machiya (traditional townhouse).

The following is a brief history of publishing, especially woodblock printing, from the website of Takezasa-do, one of Kyoto’s forerunners in this field.

〜The Edo period (1603-1868) was a time of peace and prosperity as Ieyasu united the warring states, and the center of culture shifted to the townspeople. In the beginning of the Edo period, commercial publishing took place in Kyoto, and “bookstores” that dealt in books were born. In no time, numerous bookstores lined the streets of the city, followed by the appearance of bookstores in Osaka, which fostered a publishing culture in the Kamigata region. During the Kan’ei period (1624-1645), bookstores also opened in Edo. Tsutaya Shigesaburo, who later became a major publisher of nishiki-e prints by artists such as Kitagawa Utamaro, a master of beautiful women paintings, and Toshusai Sharaku, a prodigy of actor pictures, also had a bookstore in Yoshiwara. 〜The first woodblock print shop in Yoshiwara was established by Tsutaya Shigsaburo.

〜Establishment of Traditional Woodblock Printing Techniques In order to produce large quantities of prints in a limited amount of time and at a limited cost, the ukiyo-e woodblock printing method was simplified to eliminate waste and create the unique composition and color expression unique to ukiyo-e woodblock prints. The production process was differentiated, and a three-person division of labor system was established, with the “painter” drawing the preliminary sketches, the “engraver” engraving the plates, and the “printer” printing the colors, each working as a specialist. Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro, both well-known artists, were either employed by major publishers or worked independently. Japanese woodblock multicolor printing, with its unique materials, colors, and expressions, was the world’s most advanced technique at the time. The technique later influenced many artists, including Van Gogh, and astonished the world. Trivia: Japan’s advanced woodblock printing technology became known to the world when woodblock prints that failed to print were shipped across the sea as buffer material for other exports such as ceramics and porcelain. ~.

The casual fact that ukiyo-e prints were used as packing materials for paper scraps is surprising in its permeation of popular art in the Edo period society. In contrast to European art, which had been a form of religious art or an object of service to the aristocracy’s lifestyle, Japanese woodblock-printed art, which was used carelessly as paper scraps, was a civilized wonder, and as a Japanese, I am proud to say that it brought about a sense of wonder. In the not-so-affluent lives of city dwellers, polychromatic paintings were still displayed in each household and provided a topic of conversation for the family dinner table. The paintings were often about travel or gossip about famous Kabuki stars, depending on the theme of the painting (laugh), and they added a lot of color to the peaceful family life. Of course, the high literacy rate in Japan meant that people probably had to learn and gather information from printed books, but the ease of understanding provided by multicolor printing had a powerful impact on people’s hearts. I myself am of the first generation to be imbued with the visual culture of television, but I suspect that the people who first came into contact with the Ukiyo-e culture of the Edo period were of a similar generation that experienced a cultural revolution. I love this atmosphere.

Posted on 1月 17th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪 | No Comments »