家は希望する人がいて成立する。住宅雑誌・メディアって建築要素把握と生活の関連にスポットを当てる役割。住宅の意味はそこでシアワセな暮らしが営めるかどうか、が最大ポイント。もちろん作り手の紹介は大きい要素ではあるけれど、家を希望する人にとって本当の最大助言者は、すでに建てたひとの実感だろうと思います。それを第3者的な視線で「取材」して表現していくことがメディア最大の役割。シアワセな「だんらん」生活が実現しているのかどうか、取材センサー機能を働かせて、これから建てる人に伝える役割が社会機能の中核。

そんな意識を持つと連綿と繋がってきている昔人の暮らしから現代と通底する普遍的な価値観が自然に浮かび上がってくる。ちょっと(笑)以前の時代の人間生活・民俗の歴史とか、古民家群から発掘できてくる。生活の「だんらん」には実に多様な要素、シアワセのカタチがあると思わされる。そんなことがら・ものごとを深掘りしてみたいということで、いまは江戸期房総の商家群をピックアップ中。

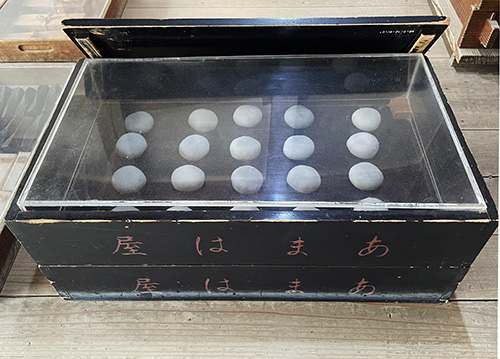

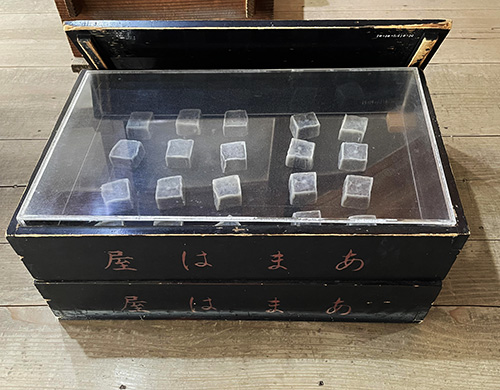

本日はひとを蕩けさせる甘味の世界・町家の「お菓子屋」さんであります。甘いものは実はその甘味料・砂糖の歴史からして実は新しい部類の人間体験だと気付かされる。

財団法人・農畜産業振興機構のHPに甘味の歴史が詳述されている。以下要旨抜粋。

〜砂糖がもたらされる以前の庶民の甘味料は、ヨーロッパでは蜂蜜であり日本では飴であった。飴はもち米などのデンプンを麦芽(麦もやし)で糖化して作られる我が国古来の甘味料。『日本書紀』において初代の天皇とされる神武天皇の即位前紀に「飴(たがね)」が記されているほか『延喜式』には平安時代の都に「糖(あめ)」の店があったとされる。

江戸時代の初めまでは餡といえばもっぱら味噌味や塩味だった。長崎に来航する唐船・オランダ船により砂糖が大量輸入されるようになると、金平糖などの南蛮菓子のほか従来の飴に加え新たに砂糖を用いた飴が作られるようになる。嘉永6年(1853)の『近世風俗志』の「饅頭」の項では「昔は菜饅頭・砂糖饅頭の二制あり。何時よりか菜饅頭は廃れ今は砂糖饅頭のみなり。今の饅頭、表は小麦粉を皮とし、中に小豆餡を納る。小豆は皮を去り砂糖を加ふ。砂糖に白黒の二品あり。昔は諸国ともに菜饅頭廃しその後は塩饅頭と云ひて小豆餡に塩を加へたり。近世は鄙といへども皆専ら砂糖饅頭なり。文化以来やうやうかくのごとくなり」とある。〜

いずれにせよ、家庭で甘味の菓子を作ることは珍しく、このような商家・町家店舗で専業的に作られて購入されていたのが実態だっただろう。砂糖の普及に伴って徐々に家庭でも正月の餅つきで「あん餅」がつきあげられるように変化していった。昭和中期までのわたしの生家でも賑やかに多量のあん餅を作っていた。その餅つきの製造場所は深く記憶に残っている。前日までの材料仕込みから家族総出での餡作り、餅つき、手ごね作業の隅々まで、深く記憶に残り続けている。年越しを飾るメインイベントとして、甘味は日本人にとって「だんらん」の豊かさを実感できる大きな機会だったことだろう。

English version⬇

Ethnographic History of Sweetmeats and Sweets -1 Edo Period, Boso Machiya-8

It was in the merchant and townhouse houses of the Edo period that “sweet foods” were first offered to the common people in their homes. The merchants and merchant houses of the Edo period were the first to offer sweet foods to the common people, enriching the Japanese home life.

A house is established when there are people who wish to live in it. Housing magazines and media are responsible for highlighting the relationship between the understanding of architectural elements and living. The most important point of a house is whether or not it is possible to live a happy life there. Of course, the introduction of the builder is a major factor, but I believe that the greatest advisor for people who want to buy a house is the experience of those who have already built one. The greatest role of the media is to “report” and express this from a third-party perspective. The core of the social function of the media is to use its sensor function of reporting on whether or not a “happy home” life has been realized, and to tell people who are going to build their own homes about it.

With such an awareness, universal values that are common to the present day naturally emerge from the lives of the ancients, which have been connected to the present day. The history of human life and folklore of an earlier era can be unearthed from the old houses. The “communal living” of daily life has a variety of elements and forms of happiness. In order to delve deeper into such things, I am now picking up a group of merchant houses in Boso during the Edo period.

Today, we are going to visit a sweets shop in a machiya, a world of sweetness that can make you fall in love with sweets. I realize that sweet food is actually a new kind of human experience, given the history of its sweetener, sugar.

The website of the Organization for Promotion of Agriculture and Livestock Industry details the history of sweetness. The following is an excerpt.

〜Before the introduction of sugar, the sweetener for the common people was honey in Europe and candy in Japan. Ame is an ancient Japanese sweetener made by saccharifying glutinous rice and other starches with malt (barley sprouts). In the “Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan),” “tajane” is mentioned in the pre-century of Emperor Jinmu, the first emperor of Japan, and in the “Engishiki (Engi Shiki),” it is said that there was a “sugar” store in the capital during the Heian period.

Until the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1867), red bean paste was usually miso or salt-flavored. When sugar was imported in large quantities by Chinese and Dutch ships that arrived in Nagasaki, new candies made with sugar began to be produced in addition to traditional candies, such as kompeito (kompeito) and other Nanban confections. In the section on “Manju” in the “Kaei 6 (1853)” (Kasei Fuzoku Shi), it is written, “In the past, there were two types of buns: na-manju and sugar-manju. From some time ago, the greens buns were abolished, and now only sugar buns are available. Nowadays, the front of the bun has a flour crust and the inside is filled with azuki bean paste. The azuki beans are removed from the skin and sugar is added. There are two kinds of sugar, black and white. In the old days, many countries abolished the “naeba-manju” and later it was called “shio-manju” (salt buns). In modern times, all the local people have been making sugar buns. It has been like this since the Bunka era. ~…~…~…~…~…

In any case, it was rare to make sweet confections at home, and the reality was that they were made and purchased exclusively at merchant houses and townhouse stores like this one. With the spread of sugar, the home cook gradually began to make “anmochi” at the New Year’s rice-cake pounding. Until the mid-Showa period, my family was making large quantities of anmochi in a lively atmosphere. The place where the rice cakes were made remains deeply in my memory. From the preparation of ingredients up to the day before, to the family’s concerted efforts to make red bean paste, to the pounding of the rice cake, to every detail of the hand-kneading process, all remain in my deepest memories. As the main event that decorates the New Year’s Eve, sweetness must have been a great opportunity for Japanese people to experience the richness of “Danran” (gather together).

Posted on 1月 15th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究, 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.