ことしはわたし自身にとって節目の年になったのですが、現代人はさまざまなステージでの生き方というのが必然的な「対応力」として求められていくことでしょう。そういうことを強く実感した。

一般的には「老後の人生」みたいなことですね。まだまだそういう着地点には到達できませんが、しかしこれまでを土台にして、現役の時には気付く余裕がなかった部分に思惟を巡らす、ということにだんだん、惹かれてきております。

必ずしも「やり残した」心理ではないのですが、そんな気分に導かれ自分なりの探索をしたい。

この草戸千軒の探訪みって、まだ自分自身でも整理がついていないことがら。どうして自分自身が強く惹かれるのか、その意味合いはよくわからない段階です。でも興味を強く持っている。

そんなことで少しマーケティング的に調査もしてみたのですが、読者のみなさんからも興味深い反応が得られてきております。たぶん先人の「生き様」みたいな部分で共有できるモノがあるのでは?

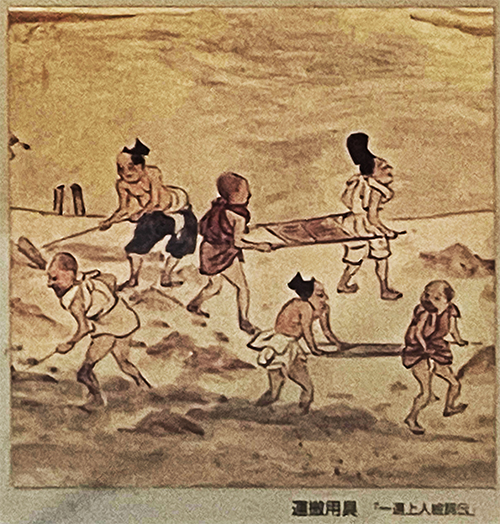

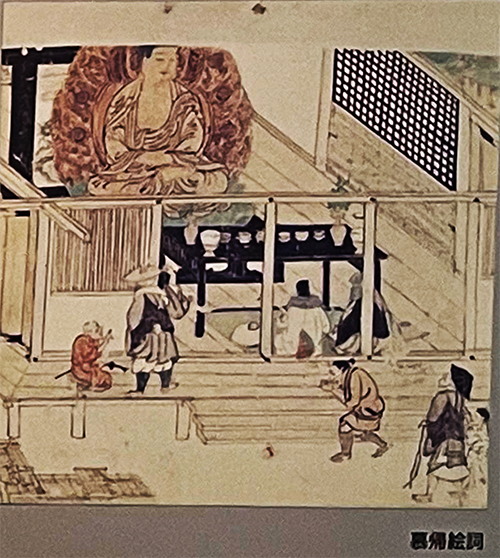

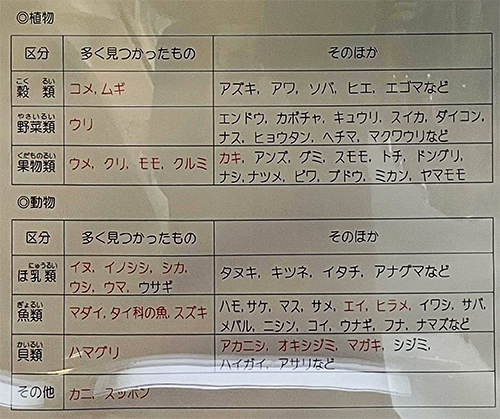

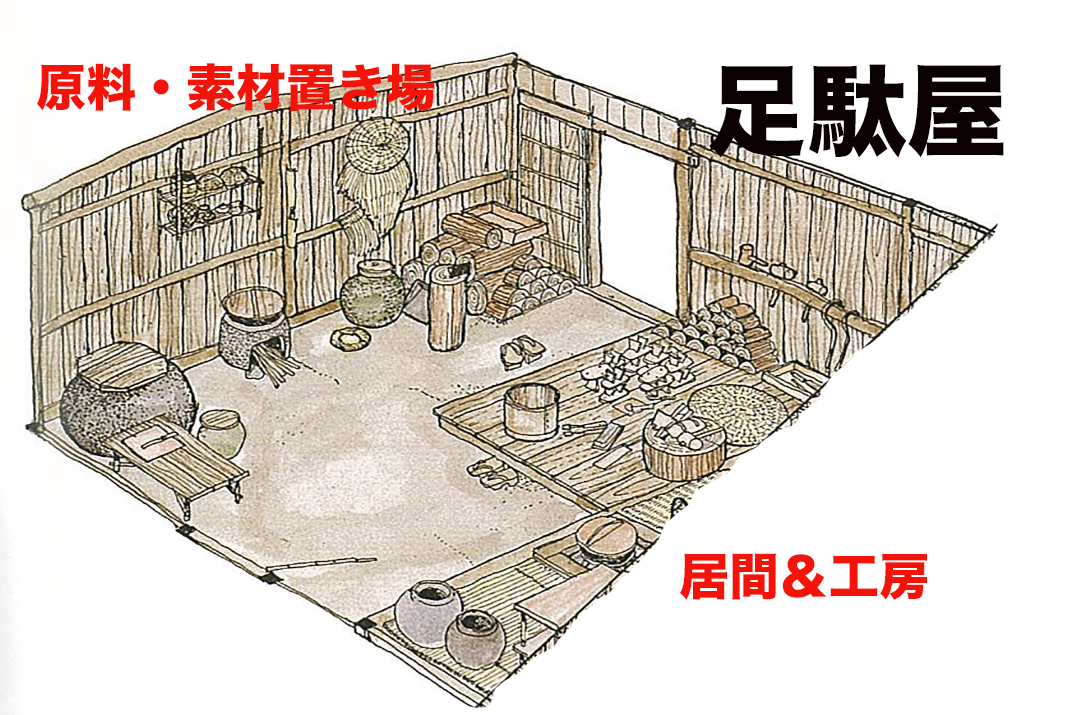

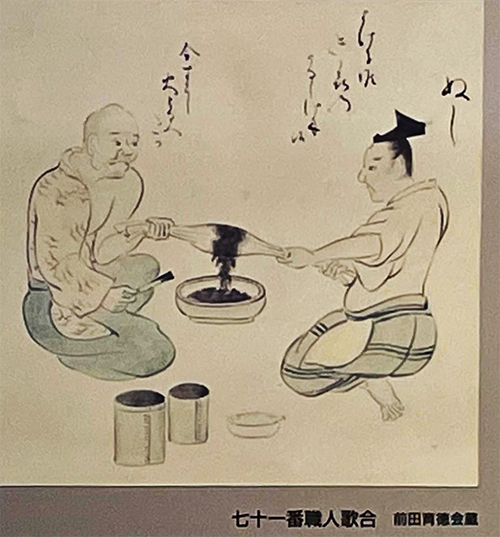

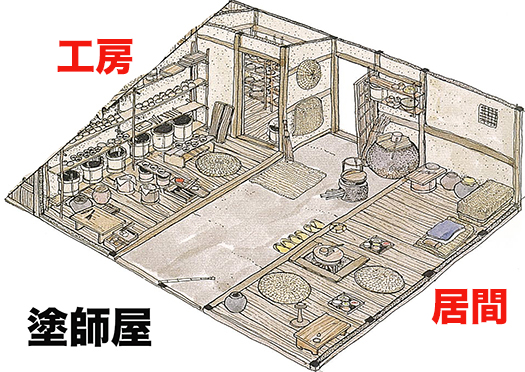

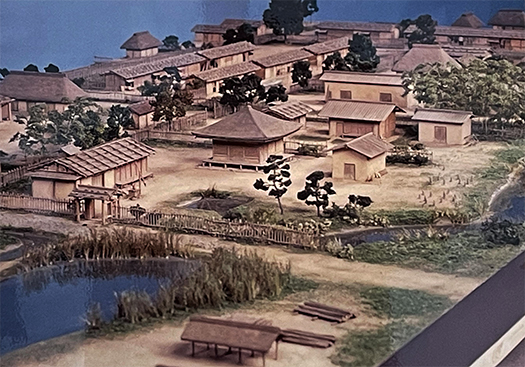

上の図版は草戸千軒の街並み復元模型と、同時代1417年に描かれた室町中期の「融通念仏縁起絵巻(東京国立博物館蔵)」の一部。中世都市というアジールには多様な人びと、世間的には「異形」と見なされる人びとの人間痕跡が描かれる。現代ニッポン人は非常に従順に企業・資本主義社会と関係しながら正しく生きているけれど、先人はもうちょっと多様だった。

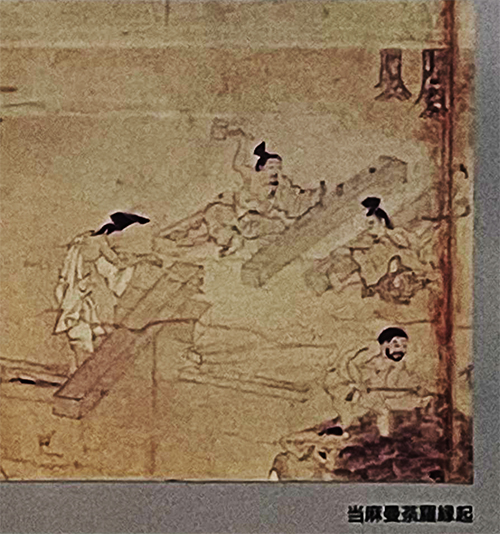

こちらは右側画面の詳細拡図。画面右上には集団で狼藉を働いていると目される「悪党」の3人組。日本社会では最近「チンピラ」という存在は見かけなくない。未曾有の「人手不足」社会でこういった「はみ出し」的存在は淘汰されているのか。よく見ると結構な年齢のようで一種職業的でもある。今回シリーズでみた足駄屋さんに特注したような「高下駄」を履いての肩衣姿。右の人物は「みせ鞘」の腰刀をさしている、とされていた。

その画面下には、乞食が描かれている。体位の表情に必死さが表現される。その乞食の左側には「覆面」の人物も。歴史家の網野善彦氏によるとこういう覆面姿という装束をあやしげに着こなす生き様の人びとが中世社会には多数存在したとされていた。氏によると「非人」ではないかとのこと。

こちらは左側画面の拡大。やや上のふたりの男性は「鉦叩き・鉢叩き」とされていた。それって「チンドン屋」という宣伝マンということか。鳴り物入りというコトバがあるけれど、中世都市で参集する大衆に対して宣伝するのに、こういう手法が編み出されたのか。市女笠姿の杖を突いた女性や、子どもを背負った女性の姿も確認できる。右上のような悪党もいるけれど、中世都市では「他人の目」という治安効果も発生したモノだろうか。どうもわたし、こういう歴史的な多様性社会、人間存在のありようと住宅とか建築・都市の関係性にどんどん導かれていっているような気がしています(笑)。

English version⬇

The Different Kinds of People Gathering in a Medieval City – Kusado-Senken 2023 Revisited – 14

I am going to be drawn to the area of historical diversity society, the state of human existence and housing, architecture and cities. What shall I do (laugh) …

This year was a milestone year for me personally, and I believe that people today will inevitably be required to live in various stages of life as a way of “coping. I strongly felt that way.

Generally speaking, it is something like “life after old age. I have yet to reach such a landing point, but I am gradually becoming more and more attracted to the idea of building on what I have done so far and thinking about things that I did not have time to notice when I was in active service.

It is not necessarily something that I have “left undone,” but I would like to explore in my own way, guided by such a feeling.

Things like this exploration of Senken Kusado are things that I have yet to sort out for myself, and I am not sure why I am so strongly attracted to them or what their implications are. But I am strongly interested.

So I have done a little marketing research, and I am getting some interesting responses from readers. Perhaps there is something we can share in the “way of life” of our predecessors?

The illustration above is a part of the “Yutsu Nenbutsu Emaki” (scroll depicting the Buddha) from the middle Muromachi period (mid-Muromachi period), which was probably drawn in 1417, the same year as the reconstruction of the streetscape of Kusado-Senken. In the asylum of the medieval city, human traces of diverse people, people who are considered “deformed” by the world, are sometimes depicted. Although modern Japanese people are living a proper life in relation to the corporate and capitalist society in a very docile manner, their predecessors were a bit more diverse.

This is a detailed zoomed-in view of the right side of the screen. In the upper right corner are three “thugs” who are believed to be committing gang violence. In Japanese society, “hoodlums” are not so common these days. In a society of unprecedented “labor shortage,” are such “outcasts” being weeded out? The figure on the right is wearing “mise-saya,” a type of geta custom-made by a geta shop, and is dressed in a shoulder-length robe. The figure on the right is said to be holding a “mise-saya” (waist sword).

Below this screen, a beggar is depicted. The expression on his body expresses his desperation. To the left of the beggar is also a “masked” figure. According to historian Yoshihiko Amino, there were many people in medieval society who wore such masked costumes in a dubious manner. According to Yoshihiko Amino, they may have been “non-humans.

This is an enlargement of the screen on the left. The two men slightly above were considered to be “gong-tappers and bowl-tappers”. Does that mean they were “chindon-ya,” or publicity men? The word “ringo” is used to describe this kind of publicity, and I wonder if this kind of technique was developed in medieval cities to advertise to the masses who gathered there. A woman with a walking stick in a straw hat and a woman carrying a child on her back can also be seen in the scene. There are also rogues like the one on the upper right, but I wonder if the “eyes of others” also had a security effect in medieval cities. I feel that I am being led more and more to this kind of historical diversity of society and the relationship between human existence and housing, architecture, and the city.

Posted on 12月 26th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »