人間・人体をどう表現するかというのは、有史以来の人類の大テーマだったでしょう。しかし非常に写実的に描かれたラスコー洞窟壁画などでは約40,000年前の頃の人類の主要な観察対象は狩猟の対象である動物群であり、同類としての人類に向けての描写葛藤を感じない。

それが古代エジプトなどではファラオに対しての表現が中心的なテーマになってくる。そういう権力者の描写と合わせて群衆的に武人などが表現されるようになる。

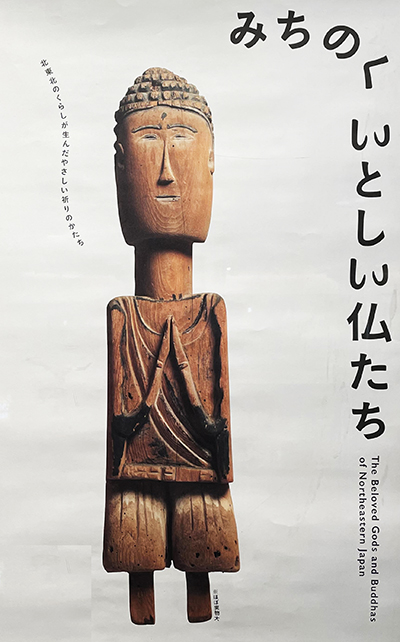

一方で日本列島では縄文期に始原を持つ土偶ではひたすら人物表現に向かって行っている。しかしエジプトのように王権などの権威への崇拝という方向は微塵も感じられない。そうであるのに、人物表現に向かっていく。それも写実的な方向で進化して行くのではなくむしろ呪術的な方向を感じる。

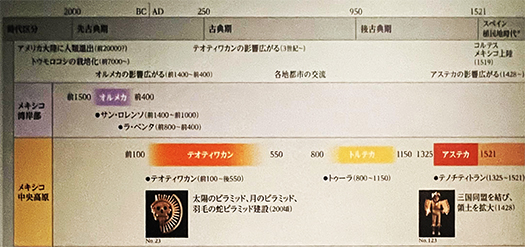

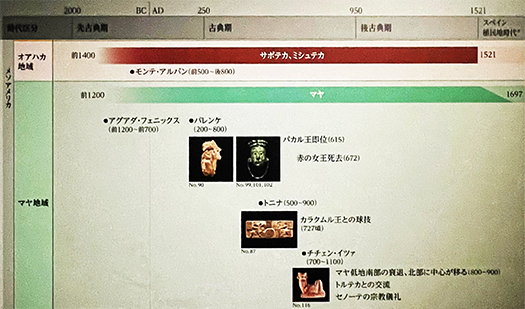

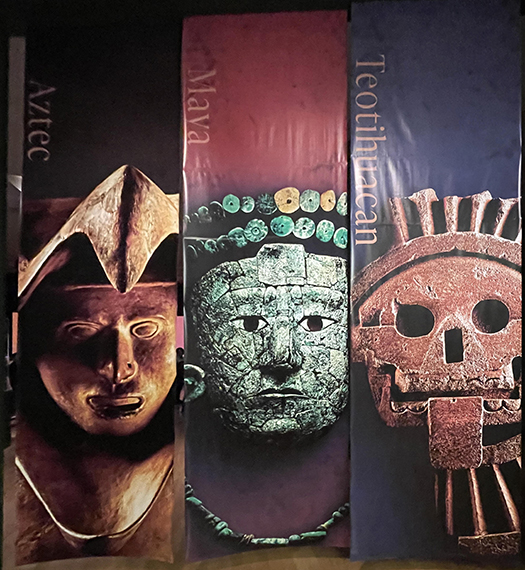

太平洋を挟んで古代メキシコでは土偶とも対比されうるような人物造形が描かれている。かれらが生み出した造形にわたしのようにシンパシーを持つ人間には、土偶との相似的な制作心理が感じられる。

表現技法であるとか、素材選択方法などで交流があったとはほぼ考えられないので、もし雰囲気が似ているとすれば、はるかなDNAのささやきのような部分での共感なのではないか。このブログシリーズで日本の古層の文化と古代メキシコを比較対照して見たいと思った動機はそんなものである気がする。

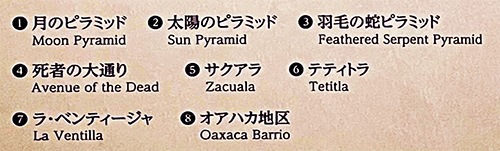

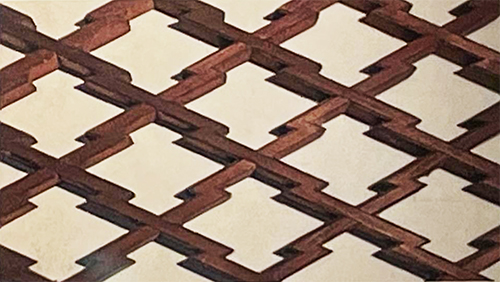

上の像は、450-550年頃の「楯を持つ小像」。顔面装飾やペンダント、ベルト、楯など典型的テオティワカン様式。こうした戦士像は墳墓の副葬品としてはまったく出土せず、こどもの玩具説もあるという。その下の「嵐の神の壁画」は背負い籠と右手にトウモロコシを持っている。生産手段としては農耕が主体だったのだろう。またテオティワカンでは多くの建物が赤を中心とした多彩色の壁画で飾られ、都市空間を彩っていたと言われている。

赤が人類の始原にも関わるような色彩感覚であるのは日本も同様だった。

日本の土偶たちはたぶんテオティワカンよりも千年以上前に造形されたと推測できる。土偶もまた、副葬品というようには見なされていない。むしろ生まれてくる命、新生への祈りの対象であったという説もある。死よりも生への祈りが土偶の本質ではないかというのだ。

女性を表現した土偶では豊かな下半身が象徴的に表現されていて、それは新生への期待感が普遍的な願いとして強く共感されていた様子を語ってくれる。人間自身が最大の生産手段であった時代、このことは切実な社会要請でもあっただろう。

ヨーロッパ人種は比較的長く「狩猟採集」を経済基盤とし続けたけれど、日本列島社会では豊かな海岸環境によって漁労という生産手段が文化揺籃されたものだろう。一方、古代メキシコもまた、トウモロコシという基本食の栽培適地としての文化性が発展したのだとも思える。

English version⬇

Clay Figures vs. Teotihuacan Figures Ancient Mexico – 6

The settlement of Japanese society began with the abundant marine resources as the basic food source. Ancient Mexico, on the other hand, was based on corn cultivation and agriculture. Similarities in the starting point of expression. The similarities in the starting point of expression.

How to represent humans and the human body has probably been a major theme for mankind since the beginning of time. However, in the highly realistic Lascaux cave murals and other paintings from about 40,000 years ago, the main object of human observation was a group of animals that were the object of hunting, and we do not feel any depictive conflict toward humans as our own kind.

In ancient Egypt and elsewhere, however, the central theme is the representation of the pharaohs. In ancient Egypt, the central theme of expression was against the pharaohs, and in conjunction with the portrayal of such powerful figures, warrior groups were also depicted.

On the other hand, in the Japanese archipelago, clay figurines, which originated in the Jomon period, have been moving toward the representation of human figures. However, as in Egypt, there is not the slightest sense of worship of authority, such as kingship. Yet, they are still moving toward the expression of the human figure. The evolution is not in the direction of realism, but rather in the direction of magic.

In ancient Mexico, across the Pacific Ocean, human figures are drawn in a manner that could be contrasted with clay figurines. For those of us who are sympathetic to the forms created by these artists, as I am, we can feel a similarity in the psychology of their work.

It is almost inconceivable that there was any exchange in terms of expression techniques or material selection methods, so if there is a similarity in atmosphere, it is probably due to a whisper of DNA. I feel that is what motivated me to compare and contrast ancient Mexico with the ancient layer of Japanese culture in this blog series.

The statue above is a “small statue with shield,” circa 450-550. The face decoration, pendants, belt, and shield are typical of the Teotihuacan style. These warrior statues have not been found as burial accessories in tombs at all, and there is a theory that they were children’s toys. The “Storm God Wall Painting” below it shows a man carrying a basket on his back and a corn cob in his right hand. Agriculture was probably the main means of production. It is also said that many buildings in Teotihuacan were decorated with colorful murals in red and other colors to decorate the urban space.

The same is true of Japan, where red is a color sense that is related to the origin of humankind.

Japanese clay figurines were probably formed more than 1,000 years before Teotihuacan. Clay figurines are also not regarded as burial objects. Rather, some believe that they were objects of prayer for life to be born, for the new birth. It is said that the essence of clay figurines is to pray for life rather than death.

Clay figurines representing women symbolically depict the abundant lower half of the body, which shows how the expectation of new life was strongly shared as a universal wish. At a time when man himself was the greatest means of production, this would have been an urgent social need.

While European peoples continued to rely on “hunting and gathering” as their economic base for a relatively long time, the rich coastal environment of the Japanese archipelago probably provided a cultural cradle for fishing as a means of production. On the other hand, ancient Mexico also seems to have developed its culture as a suitable place to cultivate corn, a basic food.

Posted on 9月 22nd, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪 | No Comments »