九州中部の熊本県と宮崎県の中間の山岳地帯。日本三大秘境と言われる椎葉地区に逃げ延びた平家一族。

きのうはそうした絶体絶命の状況で安寿と厨子王の安寿姫のように自己犠牲でこの一統を救った清盛の孫娘のことを想像してみた。わたしは民話の中でもこの「安寿と厨子王」の話に子どもこころに深く感動したことを覚えている。そういう女性の人生の生き方、いや自らを犠牲にして肉親を救おうとするタイプの愛があるのだと知って、男性として女性の偉大さに打ちのめされたようになったのだ。やはり清盛を生んだ一族の血脈としてのそういった英邁な精神が、こうした境遇の女性の選択から強くメッセージされる。ある意味では清盛の成功以上に、こうした局面でのいのちの活かし方、使い方こそが重要だと思える。

一方でそのように救われた深い山間の環境のなかで、平家落人たちはその後どのような「生き残り戦略」で、現代にまでその伝承を純粋化させて生きて来られたのか。

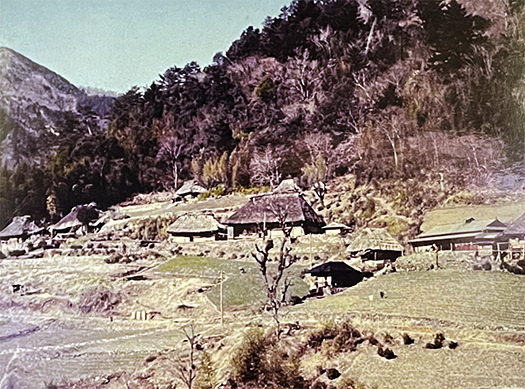

上の写真はこの展示住宅の記録パネルのなかの古画像。家々が寄り添うように山間の環境の中で共助してきたことがみてとれる。見るとおり平坦地はほとんど見られず、辛うじてネコの額のような平坦地には住宅を建てて、不整形に家並みが形成されている。強い傾斜が家屋群のすぐ後ろに迫り、下側も強い傾斜地に一定の「畑」が作られている。

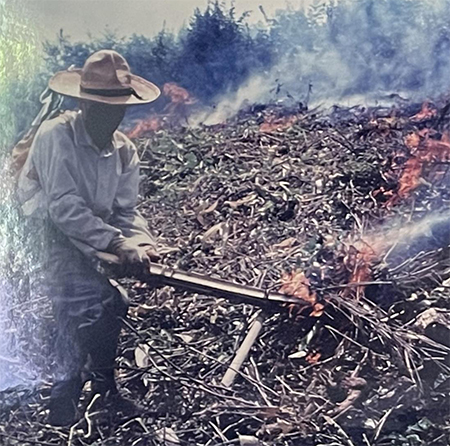

説明文ではこの集落の生業は、山での狩猟と木の実などの採集、そして焼き畑農業と記載されている。

山深い椎葉にはもちろん水田はほとんどなかった。水源確保が想像もつかない。主たる生業は狩猟とされる。民俗学者の柳田國男は遠野物語に先行してこの地・椎葉の狩猟を中心とした暮らしについて「後狩詞記(のちのかりことばのき)」として発表した。狩の故実を筆録したもの。これは「後」とされるが、前の狩詞記とは「群書類従」<1793年〜1819年>にある狩猟生活についての記載箇所のこと。

鉄砲伝来に伴って狩の道具が弓から鉄砲に代わって誰でもが狩を容易に行えるようになったことで山の鹿や猿が少なくなったことを嘆き、弓の時代の狩について記述したとされる。この源平の時代にはもちろん鉄砲はないので、平家として弓に慣れていた人びとにとって、生業としてもっとも技術転用しやすかった可能性が高い。頼朝が鷹狩りを行ったことが記録もされているので、当然弓での狩猟は生業化しやすかったのだろう。

三大秘境のどこでもみな平家落人伝承が残るのはそういう意味合いか。

しかし狩猟という「技術記録」ビジュアルは残りにくい。

焼き畑は古い農法で山の雑木を切り倒して焼き払い、そこにソバ・ヒエ・アワ・小豆などを栽培する。古写真はその乾燥の様子を表現したものと思われる。長大な縁側空間は南面していて、絶好の乾燥場所だったことだろう。この椎葉は「ヒエつき節」の本場と言われるが、そういった生活背景があると推定できる。

水田耕作が馴染まない環境の中で地域に適合させる生き方・暮らし方の開発に、必死に取り組んできた営々たる努力の数々に、深くアタマが下がる思い。

PS:新建ハウジングDisitalでの連載記事第4弾が、5/31公開されました。

ぜひ、ご一読ください。 https://www.s-housing.jp/archives/351127

English version⬇

Hunting and Gathering, Slash-and-Burn, Survival Strategies of the Heike Rakunin, Hyuga, Japan-3

How did the Heike Rakunin survive to the present day? Hunting is the best livelihood for experts of bow and arrow. Other than rice paddies, they struggled to survive by cultivating other fields. …

A mountainous region between Kumamoto and Miyazaki prefectures in central Kyushu. The Heike clan fled to the Shiiba area, which is said to be one of the three most mysterious places in Japan.

Yesterday, I tried to imagine the granddaughter of Kiyomori who saved the Heike clan by self-sacrifice like Princess Anju in the story “Anju to Kurashioh” (Anju and Kurashioh). I remember being deeply moved as a child by the story of “Anju and the King of the Kitchen,” which is one of the most famous folk tales. Knowing that there was such a way of life of a woman, or rather, a type of love in which a woman sacrifices herself to save her relatives, I felt as a man that I had been overwhelmed by the greatness of women. After all, such a heroic spirit as the bloodline of the family that gave birth to Kiyomori is strongly messaged from the choices of women in these circumstances. In a sense, the way in which life is utilized and used in these situations is more important than Kiyomori’s success.

On the other hand, what kind of “survival strategy” did the fallen Heike warriors use in the deep mountain environment where they were saved, and how were they able to keep their traditions pure and alive until the present day?

The photo above is an old image from the record panel of this exhibition house. The houses are nestled together in the mountainous environment, as if they were cooperating with each other. As you can see, there is hardly any flat land, and houses have been built on the flat land that barely resembles a cat’s forehead, forming an irregularly shaped row of houses. A strong slope looms immediately behind the houses, and on the lower side, too, a certain amount of “fields” have been built on the strong slope.

The description describes the village’s occupation as hunting and gathering nuts in the mountains and slash-and-burn agriculture.

There were, of course, few rice paddies in mountainous Shiiba. It is hard to imagine how to secure a water source. The main occupation is said to be hunting. Folklorist Kunio Yanagida Kunio published a book titled “Nochino Kari Kotonoki” about life in Shiiba, which preceded Tono Monogatari (Tales of Tono) and centered on hunting. This is a written record of the facts of hunting. This is said to be a “later” version, but the former Kari Kotonoki refers to the description of the hunting lifestyle in the “Gunsho Ruishu” (1793-1819).

It is said that the author lamented the decrease in the number of deer and monkeys in the mountains as hunting tools were replaced by guns instead of bows with the introduction of guns, making hunting easier for everyone, and described hunting in the age of the bow. Since there were, of course, no guns in this Genpei period, it is highly likely that it was easiest for people who were accustomed to archery as Heike to convert their skills into a livelihood. Since it is recorded that Yoritomo (1522-1591) engaged in falconry, hunting with a bow would naturally have been an easy occupation for him.

This may be the reason why there are still legends of the Heike Rakunin in all of the three most remote areas in Japan.

However, it is difficult to preserve a visual “technical record” of hunting.

Yakihata is an old agricultural method in which small trees are cut down and burned, and buckwheat, Japanese millet, millet, azuki beans, and other crops are cultivated on the land. The old photographs are thought to represent the drying process. The long porch space faces south and would have been a perfect drying place. It is said that Shiiba is the home of “hiyetsuki-bushi,” and it can be assumed that this is the background of the daily life of this area.

I am deeply humbled by the efforts made to develop a way of life and livelihood that fits the region in an environment where rice paddy cultivation is not used.

PS: The fourth installment of our series of articles on Shinken Housing Disital was published on May 31.

Please take a look.

Posted on 6月 3rd, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 歴史探訪

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.