きのう、出張からようやく帰還。この時期の移動では服装がまったく予測できませんね。札幌から関東へ行ったわけですが、札幌では自然にダウンジャケット。一方の関東ではサクラも開花という情報があって「え、どうしよう」ですね。わたしは自由の愛好者(笑)なので、なるべく身軽に動きたくて荷物はリュック1個に収めたい。一応ビジネスとしてのジャケットは1枚着ているので、外套をどうするか、悩ましいところ。今回は大成功でダウンジャケットのままでしたが、東京はこの時期としては寒い方で推移していましたね。途中、地震のアラートでちょっと驚かれされたけど(笑)。

さて、きのうのブログで宗教と美術について日頃感じていることを書いたのですが、風神雷神図についても触れたところ、読者の方からその風神雷神について、中国・莫高窟の似た画像の指摘があった次第です。

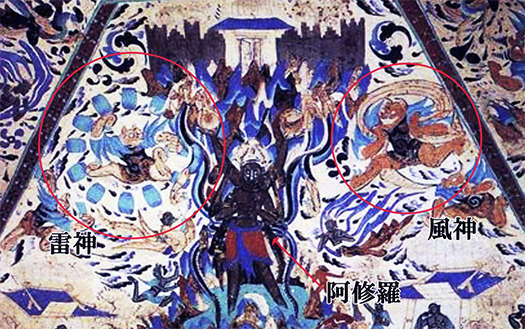

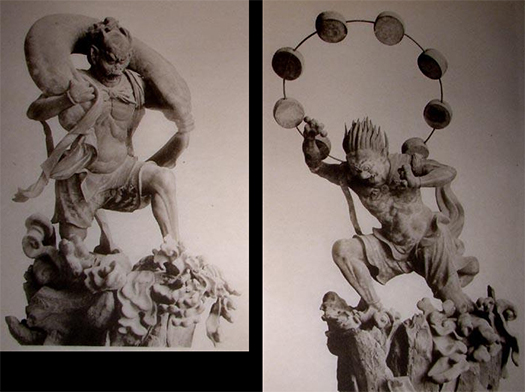

そういうきっかけがあってのブログなのですが、上の図は俵屋宗達の「風神雷神図屏風」と中国莫高窟の壁画、そして1190年代に建てられた三十三間堂に収められた風神と雷神の像であります。わたしとしては画家・俵屋宗達の風神雷神図に深く傾倒しているものですが、さりとて金科玉条のように「独創オリジナル」と思っているワケではありません。

宗教画としてのモチーフとしてはかなり一般的なものだといえるのでしょう。ただ、指摘を受けるまで風神雷神のことを調べてみるような動機は持っていませんでした。美術作品として「だけ」見る、という現代人のごく一般的な常識に従っていた。言われてみれば風神雷神図の社会的機能としては宗教のためのひとつの表現として依頼され成立した画業であることは間違いない。

そんなことからチラチラと読みあさってみると、風神雷神は古代のインドに由来する「地神」格が出自のように思われますね。一方の雷神は中国の同様神格「雷公」が出自のようです。

そういったアジア各地の地神たちが、仏教という宗教の中でそれぞれに役割を配置されて、日本には風神雷神というワンセットで導入されてきたのでしょう。一神教ではない仏教の発展スタイルにこのことは関わっているのかも知れませんね。このようなことからやがて日本社会で「本地垂迹説」というものが盛り上がっていく由縁であるのかも知れません。世界宗教としての仏教にはそういう一種の「統合性」が特徴でアジア人には受容しやすかったのかも。

三十三間堂の像2体については画家の俵屋宗達はとくに仔細に検討したことでしょう。

しかし莫高窟にせよ三十三間堂にせよ、現代日本で「風神雷神図」といえば俵屋宗達や尾形光琳、酒井抱一の時代を超えた美術作品の競作に興味が集中している。逆に言えば、どうしてそこまで日本人はかれら画家たちの作品に共感し続けてきたのか、こっちの方がより興味深いと思っています。

English version⬇

Wind God and Thunder God – Religions and Deities of the Asian World

The wind god of ancient India and the thunder god derived from the thunder lord of China. Asian earth gods incorporated into non-monotheistic Buddhism. Did the Japanese accept them as pure art in a non-religious manner? …

I finally returned from a business trip yesterday. Clothing is completely unpredictable when traveling at this time of year. I went from Sapporo to Kanto, and in Sapporo I naturally wore a down jacket. On the other hand, I heard that cherry blossoms are in full bloom in the Kanto region, which makes me think, “Oh, what should I do? I am a lover of freedom (lol), so I want to move as light as possible and keep my luggage in a single backpack. Since I am wearing one jacket for business purposes, I am wondering what to do with my cloak. This time I was very successful and kept my down jacket on, but Tokyo remained on the cold side for this time of year. I was a bit startled by an earthquake alert on the way (laugh).

In my blog yesterday, I wrote about my daily thoughts on religion and art, and I mentioned the Wind God and Thunder God, and a reader pointed out similar images of the Wind God and Thunder God at Mogao Grottoes in China.

The above images are from Sotatsu Tawaraya’s “The Wind and Thunder Gods,” a wall painting of the Mogao Grottoes in China, and a statue of the Wind God and Thunder God in Sanjusangendo, a temple built in the 1190s. I am deeply devoted to the Wind and Thunder Gods by the painter Sotatsu Tawaraya, but this does not mean that I consider them to be “original” as if they were some kind of golden rule.

It is a fairly common motif in religious paintings. However, I had no motivation to look into the Wind God and Thunder God until you pointed it out to me. I was following the very common sense of modern people, which is to look at it “only” as a work of art. If you ask me, there is no doubt that the social function of the Wind God and Thunder God painting is that it is a painting work that was commissioned and established as one form of expression for religion.

From this, it seems that the Wind God and Thunder God originated from the “earth god” status that originated in ancient India. On the other hand, the god of thunder seems to have originated from a similar Chinese deity, the “Thunder God.

These local deities from various parts of Asia have been assigned different roles in the religion of Buddhism, and have been introduced to Japan as a single set of Wind God and Thunder God. This may have something to do with the development style of Buddhism, which is not a monotheistic religion. This may be the reason why the theory of “Honji-dakujaku” (manifestation of the true nature of the Buddha) eventually gained momentum in Japanese society. Buddhism as a world religion may have been characterized by a kind of “integrity” that made it easy for Asians to accept.

The painter Sotatsu Tawaraya must have examined the two statues at Sanjusangendo in particular.

However, whether it is the Mogokutsu or the Sanjusangendo, the interest in “Wind and Thunder Gods” in contemporary Japan is concentrated on the timeless works of Sotatsu Tawaraya, Korin Ogata, and Hoitsu Sakai, whose works are in competition with each other. Conversely, I am more interested in why Japanese people have continued to sympathize with the works of these artists to such an extent.

Posted on 3月 24th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.