ふとしたことから昭和40年に制作された「高校生向けの地図」と対面してしまっていた。知人からなにげに貸し出されていて、そのまま書棚に仕舞い込まれていたものが、今回の書棚の断捨離の結果、どうにも「居場所」がなくなってたったひとつだけ、類縁がなく表に出てきたといったところ。

よく考えて見たら、わたしの高校時代に2年先行していることもわかった。たぶん知人の兄姉が高校の教科書として購入していたものだったのだろう。わたしにはそういう趣味はないけれど、ほかの教科書類はさっさとゴミ出しされても、地図だけは利用価値を見出されて保存されるケースがあるという。

というような「数奇」な経緯で、わたしの目の前に59年前の地図が開かれていた。

地図だけはなんとなく保存され続けるという意味がよくわかった(笑)。

ようするに地図はタイムトンネルなのだと深く実感。人間社会というのはいま生きている現代に至るまで「歴史時間」が積層されてきている。通常、十年ひとむかしというコトバがあるけれど、「現代」という時間の特定感覚はその程度なのだろう。それを超えると、時間がそこで静止しているような印象が強くなる。ペットのイヌの寿命とも同期できるような時間感覚だろうか。

そういう時間を超えてくると徐々に「過去」というよりも「歴史」というカテゴリーに入っていくと思えるのです。約60年というなかでは日本社会は激変してきていて、現代の認識からは相当のギャップがある。そしてそういう出会いからの時間との「対話」には独特の気配が発生する。

寿命が延びてきた現代人は、たぶんこういう過去との対話機会が飛躍的に増えていくのだろう。

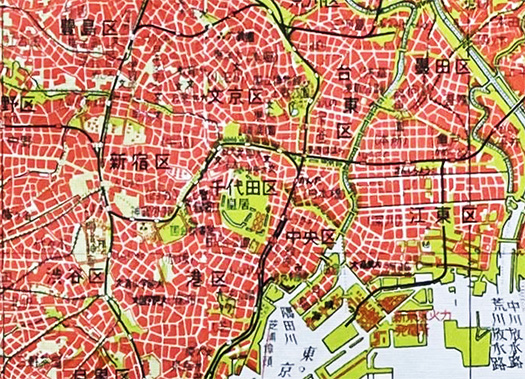

写真としては札幌の周辺図と東京都心の地図を上に挙げた。札幌周辺ではわたしがいま住んでいるもっとも近い地名として「琴似」が表現されているけれど、この59年前当時は札幌では「区制」も敷かれておらず、札幌市ではあったけれど「琴似町」というカタチで「もっとも近い隣接集落」みたいな存在だった。

東京では山手線内を中心にクリップしたけれど、もちろん高速道路も描かれていない。新宿以外のターミナル駅名も表記されていない。当時13才だった中学生のわたしにしてみれば、激しく憧憬と未来性を感じていた地域だけれど、なにか牧歌的な表現になっている。それがまた、興味を掻き立てたか。

そんなタイムトンネルの中に入り込んだ意識から、「あの辺は当時、どんな様子だったのか」という好奇心も盛り上がっていく。つい最近まで書いていた「熊野」地域にも目が行って、「鬼ヶ城」などの活字を発見すると、当時の人間の地名価値判断との対話が芽生えてくる。地図に地名がどのように扱われているかという当時の常識感覚との対比。

こういう「約60年」というワンスパンでの時間把握の感覚を持つと、その先にある江戸期のひとびととの当たり前の対話、想像力の豊穣を感じられるようになる。まぁ歴史数寄の地図からの妄想。

やがてこういう時間のなかで自分自身も積層の小さな部位になっていくことへのリアリティを感じる。

English version⬇

[Familiar time tunnel 59 years ago, map “history” feeling

The geographical perception of time change. The time in which I lived, and already a great sense of distance. I have the feeling and realization that I will soon become a piece of that time and space. I am going to be a piece of that time and space.

I was suddenly confronted with a “map for high school students” produced in 1965. It had been casually lent to me by an acquaintance, and had been tucked away on a bookshelf, but as a result of this bookshelf decluttering, it had somehow lost its “place,” and only one of them has surfaced, unrelated to the others.

I thought about it and realized that it preceded my high school years by two years. Perhaps an acquaintance’s brother or sister had purchased the book as a high school textbook. I don’t have such a hobby, but I heard that in some cases, maps are kept because people find value in using them, even though other textbooks are quickly discarded.

So, by such “strange” circumstances, a map of 59 years ago was opened in front of me.

I now understand what it means that only maps continue to be preserved somehow (laughs).

In short, I realized that a map is a time tunnel. Human society has been layered with “historical time” up to the present day, the time in which we live. There is a common expression, “a decade ago,” but the sense of specificity of the “present time” is probably about the same level. Beyond that point, time seems to stand still. It is a sense of time that can be synchronized with the life span of a pet dog.

It seems to me that once you go beyond that kind of time, you gradually enter the category of “history” rather than “the past. In about 60 years, Japanese society has changed drastically, and there is a considerable gap from the present-day perception. And a unique sign occurs in the “dialogue” with time from such encounters.

As people’s lifespan increases, the opportunities to interact with the past will probably increase dramatically.

I have included a map of Sapporo and a map of central Tokyo above as photographs. In the Sapporo area, “Kotoni” is shown as the name of the nearest place where I live now, but 59 years ago, Sapporo did not have a ward system, and although it was part of the city of Sapporo, it existed as “Kotoni-machi” and was like “the nearest neighboring settlement.

In Tokyo, the clips were taken mainly within the Yamanote Line, but of course there were no expressways depicted. Terminal stations other than Shinjuku were not indicated. As a 13-year old junior high school student at the time, I was very attracted to this area and felt a sense of futurism, but there was something idyllic about the way it was depicted. Perhaps that is what aroused my interest in the area.

From the awareness of having entered such a time tunnel, one’s curiosity about “what that area was like back then” is also aroused. When I look at the “Kumano” area, which I had written about only recently, and discover printed words such as “Onigajo,” a dialogue with the place name value judgments of people of that time begins to grow. Contrast this with the common sense sense of the time about how place names were treated on maps.

When we have a sense of grasping time in the span of “about 60 years,” we can have a dialogue with the people of the Edo period and feel the richness of imagination that lies ahead. Well, it is a delusion from the map of history.

I feel a sense of reality that I myself will eventually become a small part of the stacked layers in this kind of time.

Posted on 2月 14th, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.