この蓮見家住宅は江戸中期の農家住宅の典型的な仕様だと言われる。広間型三間取、寄棟造、茅葺。桁行七間(16.8m)梁間三間半(5.5m)。江戸市中では庶民は長屋に住み住み暮らしていた時代。一般的にはこういった農家の次男三男層は、この生家を離れて江戸に向かい、そこで職を見つけて長屋に住み、立身することを夢見ていたが、その多くは夢破れて帰る故郷もないまま、刹那的な人生を生きた時代。

広島県東部で暮らしていたわが家の江戸期の過去帳などを見てみても、身分制固定化社会での生きにくい現実の断片を証立てる現実に突き当たって、胸苦しさを覚えたりもする。夢見がちな幼少年期を過ぎてくれば、こういった現実に早々に放り出されただろう。そうであっても盆暮れなどには帰省することもあり、いっとき親子兄弟、幼なじみたちと屈託のない時間を過ごせただろうか。

しかし生家を継ぐ長男層としても厳しい年貢取り立て圧力のなかで苦しい生き様だったことはあきらか。そういうなかで、なんとか自作地を工夫して商品作物、この地域では幕末期などには輸出産業として活性化した養蚕業のためのクワを栽培して生き延びてきたのだろう。開国して経済的に自立できることへの期待感というのは民の側に大きかったに違いない。幕末期に自然発生した社会運動「ええじゃないか」の真実か。

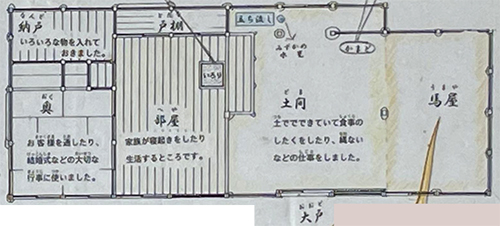

住宅内部は間取り図の向かって右に間口の半分以上の土間を取り、土間に沿って梁間いっぱいに板の間のヘヤ、その上手にオクと、その裏側にナンドを配した、いわゆる三室広間型の間取り。ヘヤには囲炉裏を設け、囲炉裏に接し土間側に板敷きの床を張り出していて、このヘヤ後方には戸棚を造りつけている。だいたい計算してみるとこの「板敷きの間」は収納のナンドを含めて10坪程度20-22畳程度だろう。日本人の生活空間とは基本的にこのような形式であって、戦後普遍化した「個人主義」的な個室間取りというものとは無縁。

よく見てみるとこの板敷きのヘヤにだけ天井が張られている。やはり主要な生活空間では「断熱」の切実な工夫として密閉化を図った痕跡だろう。仕上げ的には竹簀子天井になっており、囲炉裏には火天がある。

唯一の畳敷きのオクには天井が張られておらず、屋根の裏側を直接見ることになる。座敷飾りとして床の間と仏壇、戸棚が設けられている。どのように使われたかの記録はないが、基本的には冠婚葬祭的なハレの場として利用されて、普段は寝室的な利用をされたものだろうか。

面積103㎡(約31坪)。正面から見て右側が馬屋の入口、左側が土間の入口となっている。土間と馬屋の間は柱が1本立っているだけで、馬屋に柵が設けられておらず、床も土間と一体となっている。

具体的な江戸期の庶民の暮らしようが立ち上ってくるたたずまい。

English version⬇

Edo Period Farmhouse / Floor Plan and People’s Lives: Development Farmhouse in Urawa-5

The state of the common farmhouse in the middle Edo period. The division of how the eldest son and the second and third sons stand. The severe way of life of each can be seen. ・・・・.

This Hasumi family residence is said to have typical specifications of a mid-Edo period farmhouse. It is a three-room, wide-plan house with a hipped roof and thatched roof. It has a girigakukan of 7 ken (16.8 m) and a beam span of 3.5 ken (5.5 m). In the Edo period, common people lived in row houses. Generally, the second and third sons of these farmers left their birthplace and headed for Edo, where they found jobs and lived in tenements, dreaming of a successful life, but many of them lived a transitory life without a home to return to.

When I look at the Edo period ledgers of my family, who lived in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, I sometimes feel a sense of bitterness as I come face to face with a reality that testifies to the fragments of a reality where life was difficult in a society with a fixed status system. If I had passed through my dreamy childhood, I would have been thrown out of this kind of reality as soon as possible. Even so, I would have returned home at the end of the Bon holidays and spent some carefree time with my parents, siblings, and childhood friends.

However, it is clear that even for the eldest sons who succeeded to the family of their birth, life was difficult under the severe pressure of collecting tribute. In such a situation, they must have managed to survive by devising ways to cultivate their own land to grow commodity crops, such as mulberry for sericulture, which became an active export industry in this region at the end of the Edo period. There must have been a great sense of anticipation on the part of the people that they would be able to open up the country and become economically independent. Is this the truth of the “ee-jana-nai” social movement that spontaneously emerged at the end of the Edo period?

The interior of the house has an earthen floor more than half the size of the frontage on the right side of the floor plan, a wooden floor with a hearth between the beams along the earthen floor, an oku (a small wooden box) on the upper side, and a nando (a wooden stand) on the back side, in a so-called three-room, wide-room layout. The hearth is set in the hearth, and a wooden floor is placed on the earthen floor side of the hearth, and a closet is built behind the hearth. The “itashiki-no-ma” is about 20-22 tatami mats, including the storage nandos, and is about 10 tsubo (about 1.5 square meters) in area. Japanese living space is basically in this form, and has nothing to do with the “individualistic” private room layout that has become universal since the end of World War II.

If you look closely, you can see that the ceiling is stretched only over this wooden floor. It is probably a trace of the attempt to seal the main living space as an earnest device for “heat insulation. The ceiling is finished with bamboo screens, and there is a fire pit in the sunken hearth.

The only tatami-matted oku does not have a ceiling, and the view is directly behind the roof. An alcove, a butsudan (Buddhist altar), and a cupboard are installed as part of the tatami room decorations. There is no record of how it was used, but it is likely that it was basically used for ceremonial occasions such as weddings and funerals, and was usually used as a bedroom.

The area is 103 square meters (about 31 tsubo). The entrance to the stable is on the right when viewed from the front, and the entrance to the earthen floor is on the left. There is only one pillar standing between the stable and the earthen floor, and the stable is not fenced in, and the floor is integrated with the earthen floor.

The floor is also integrated with the earthen floor. This is the kind of appearance that brings to mind the lifestyle of ordinary people in the Edo period.

Posted on 7月 23rd, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.