現代のわれわれの家づくりと江戸期の武家の家づくりはその建築の動機に於いて大きく相違する。というか、現代は個人主義がようやくに根付いた社会であり、人間の素朴な価値感、いごこちの良さとかが最優先されてくるようになった。北海道で進化した高断熱高気密技術などは、あたたかい家という身体的感受性にジャストフィットする目的がわかりやすく実現している。そういう志向性はいかにも民主的なものだと思う。

こういう目線の目的性は北海道の開拓殖民という国家目標に淵源を持つ。北海道の開発が明治まで遅れたのは、温暖地を前提とした稲作農業が日本社会の基本だったことが反映している。蝦夷地・北海道では稲の栽培が実現していなかった。そういう国家社会に対して南下侵略を国是にするロシア国家が北海道島の支配を狙ってきたことで「国防」という観点から開拓殖民が絶対の国家意志になっていった。幕末の政治動乱・沸騰はこのロシアによる外圧が前提にあって、ペリー来航が決定打になった。

なんとか日本民族がこの北辺の地域で暮らしていけるための住宅革命が必須になったのだ。北海道開拓を推進した黒田清隆は自ら屋根の大工工事をこなせたのだという。寒冷地住宅への武人的行動力と執着を見る思い。近年までの住宅政策当局などとは相当違うモチベーションを持っていた。

しかし、一方で北海道以外では明治初年からの海外住宅の輸入はただただデザインのみの導入だった側面もある。そういう志向性の根っこには「うわべだけ」「見た目だけ」という刷り込まれた日本的性向があったように思われる。このような住宅への態度はこの写真で見る「武家住宅」のデザイン思想があるように思えてならない。

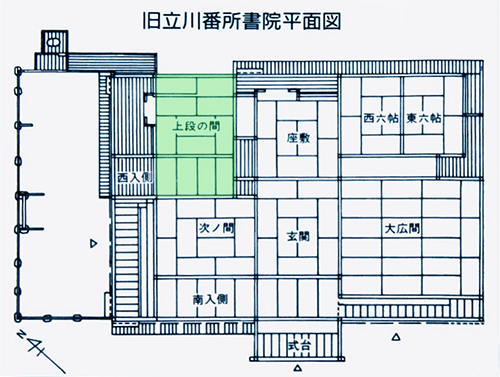

いちばん上の写真は参勤交代時での土佐藩藩主が使う部屋。部屋自体に視覚的な額縁装置が仕掛けられている。床面も1段上げられて、いかにも「上段の間」。付き従う従者たちに「威厳を示す」ことが最優先されたデザイン性志向。いかにも「床柱が似合う」尊貴性表現が建築として重視されている。

畳という床材は日本独特であり、それを前提とした「格式空間」は独自に進化した日本的高級感表現なのだろう。基本的に居住性よりも「格式」重視の志向性が強い。こういった審美的感性は日本人に受け入れられてきたものだろうけれど、世界的普遍性からは遠いと思われる。

北海道住宅では今日、ほとんど和室自体が作られなくなりつつある。写真のような日本的DNA的な美感、感受性というものはやはり現代日本ではそこから脱却してきた建築文化世界なのだと思う。

English version⬇

The Tosa Domain’s Former Tachikawa Bansho Shoin -3 – Samurai Architectural Ideas Prioritizing “Visibility

Efforts to improve the interior climate of the house have been ignored, and the design spirit has been devoted to the expression of “prestige,” so to speak, the samurai spirit. …

There is a big difference in the motive for building a house between our modern house building and that of the samurai families of the Edo period. In fact, today we live in a society where individualism has finally taken root, and a sense of simple human values, such as comfort, has come to be given top priority. The highly insulated, airtight technology that has evolved in Hokkaido, for example, has easily realized the goal of a warm house that is just right for physical sensibilities. Such an orientation is very democratic.

This objective has its origins in the national goal of Hokkaido’s development and colonization. The delay in the development of Hokkaido until the Meiji period (1868-1912) reflects the fact that rice agriculture, which was based on warm climate, was the basis of Japanese society. Rice cultivation had not been realized in Ezo and Hokkaido. In response to such a national society, the Russian state, which made it its national policy to invade southward, came to seek control of the island of Hokkaido, and from the perspective of “national defense,” frontier colonization became the absolute national will. The political upheaval and upsurge at the end of the Edo period was premised on this external pressure from Russia, and Perry’s arrival in Japan was the decisive factor.

A housing revolution became essential for the Japanese people to somehow live in this northern region. Kiyotaka Kuroda, who promoted the development of Hokkaido, was able to do the carpentry work for the roofs himself. This is an example of the warrior-like energy and persistence to develop cold-weather housing. His motivation was quite different from that of the housing policy authorities until recently.

On the other hand, however, the importation of foreign housing from the early Meiji period outside of Hokkaido was simply an introduction of design. At the root of this orientation seems to have been an imprinted Japanese tendency toward “only the surface” and “only the appearance. This attitude toward housing seems to have been the design philosophy behind the “samurai residences” shown in these photos.

The top photo is a room used by the lord of the Tosa Domain during the daimyo’s visit to Japan. The room itself has a visual framing device. The floor has been raised one step to give the room a “kodan-no-ma” appearance. The room is design-oriented, with the highest priority given to “showing dignity” to the followers. The architectural emphasis is on the expression of nobility that “suits the tokobashira”.

Tatami flooring is a uniquely Japanese flooring material, and the “prestigious space” based on it is a uniquely evolved expression of Japanese luxury. Basically, there is a strong emphasis on “prestige” rather than livability. This aesthetic sensibility may have been accepted by the Japanese, but it is far from universal.

In Hokkaido, Japanese-style rooms themselves are becoming less and less common. I believe that the Japanese DNA of aesthetics and sensibility, as shown in the photo, is an architectural and cultural world that has been displaced by modern Japan.

Posted on 4月 22nd, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.