家づくりのプロセスをウォッチし続けてきた住宅雑誌として

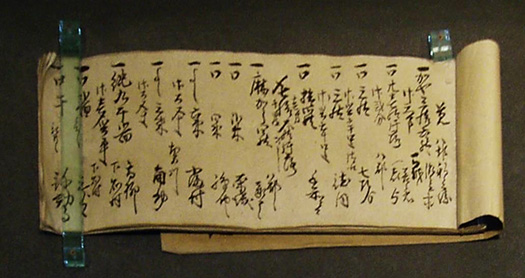

歴史的に「古民家」とされる家がどのような「建築工程」だったか、

探訪してみたいと思っています。参照資料は江戸期の「普請帳」記録。

とくに農家住宅の場合は、ムラ社会共同体というものが

まさに経済単位として地域が生き抜いていく社会基盤であり、

地域を代表する庄屋などが共同体運営に「民主的」に関わっている様が見える。

ムラの「寄り合い」などで地域の共有すべきテーマ、

その年の年貢貢納計画を立案し、それぞれの成員の負荷割合を定め、

それ以外の収入策、共有する山林などからの薪炭、あるいは木材資源など

江戸期の流通経済に参加する現金収入の共有管理も行っていた。

それこそ詳細な「予算組み」を準備して不慮に備えたと思われる。

こうした経済共同体としての同胞意識が強い絆を作り出していた。

ムラ共同体関係性の他方で武家支配のさまざまな桎梏があり、

それぞれの藩・地域で支配について「まだら模様」が生じていたのだろう。

こうした関係性が破綻したとき、一揆という強訴も発生したのだろう。

ムラ社会共同体の運営経験が日本人に独特のDNAとして刷り込まれた・・・。

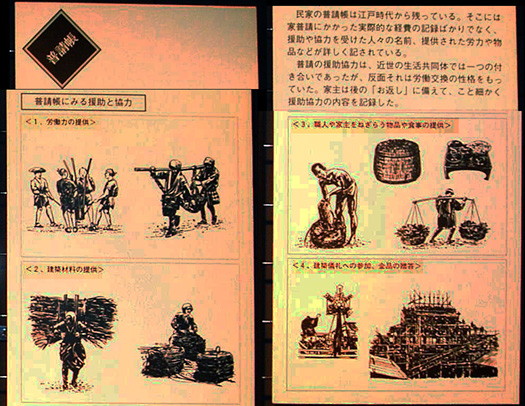

こうした共同体のなかでの建築的営為として農家住宅建築があった。

現代のように個人が単位として社会と直接向き合うのではなく、

いわば共同体を通しての経済行為として建築もあった。

受益は各戸が受けたけれど、それは共同体の総意で実現され、

乏しい現金収入のなかで部材購入を極力低減化させて、

どうしても発生する大工手間・職人手間賃にだけそれを宛て、

それ以外は共同体全員での「労働奉仕」「資材提供」が基本になっていた。

そういった状況が「普請帳」などに克明に記録されている。

たぶん年貢貢納という決算時にはこうした記録も上梓されて

ムラ共同体の財政出納の重要なパーツを形成もしただろう。また、

労働奉仕や資材提供などは詳細に記録し成員同士の返礼のため保存した。

なにやら現代の地方自治体・民主主義以上の血の流れを感じさせられる。

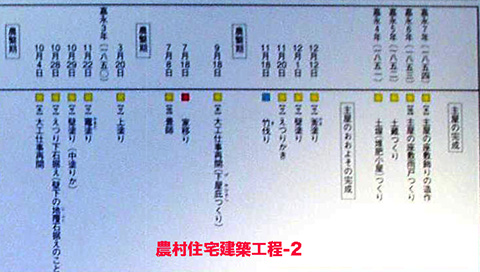

きのうの工事記録の続篇。

この記録の残る住宅建築では1849年春に工事着手している。

共同体成員の主たる生産業務は農作業なので、田起・田植えなどの

集中する春耕期前に着手されて、農繁期の工事中断を何度か挟んで、

1850年7月18日には「家移り」引っ越しをしている。

工事期間で言えば1年4ヶ月であり、共同体にとって一種の公共事業。

これだけの世話になって出来上がることから、

地縁関係というのはより深く刻み込まれていったといえる。

しかし、主屋の最後の工事の「座敷づくり」は1854年まで掛かっている。

想像だけれど、座敷などの格式空間はムラ共同体の共同事業を離れ、

各戸ごとに大工職人と話し合って工程を組んだのかも知れない。

大工職人は一定地域内で期間を決めて現場を転々としたに違いなく

その日程については大工の都合にあわせて決定されたように思われる。

・・・ムラ社会共同体での家づくりというのが、

日本人社会のなかに深く行動規範として沈殿したと思います。

たくさんの建築儀礼が営まれているけれど、

こうした共同性を見てみれば深く納得できる部分がありますね。

English version⬇

[Mura community house building (after) / Japanese good house ㉘-2]

As a housing magazine that has been watching the process of building a house

What kind of “building process” was the house historically regarded as an “old folk house”?

I would like to explore. The reference material is a record of the “general contract book” of the Edo period.

Especially in the case of farmhouses, the uneven social community

It is a social foundation for the region to survive as an economic unit.

It seems that Shoya, who represents the region, is involved in “democratic” community management.

Themes that should be shared by the region, such as Mura’s “closeness”

Make an annual tribute plan for the year, determine the load ratio of each member,

And other income measures, fuelwood from shared forests, wood resources, etc.

It also shared and managed cash income that participated in the distribution economy during the Edo period.

It seems that they prepared a detailed “budget set” and prepared for it unexpectedly.

This kind of compatriot consciousness as an economic community created a strong bond.

While there is a mura community relationship, there are various samurai-dominated swords,

There may have been a “mottled pattern” of control in each clan / region.

When such a relationship broke down, there would have been a strong complaint of rebellion.

The management experience of the Mura social community was imprinted as a unique DNA for Japanese people.

There was a farmhouse construction as an architectural activity in such a community.

Rather than the modern individual facing society directly as a unit

So to speak, architecture was also an economic act through the community.

The beneficiaries were received by each household, but they were realized by the consensus of the community.

By reducing the purchase of parts as much as possible in the scarce cash income,

Address it only to the carpenter’s labor and craftsman’s labor that inevitably occurs,

Other than that, the basics were “labor service” and “material provision” for the entire community.

Such a situation is clearly recorded in the “Public Contract Book”.

Perhaps such a record was also published at the time of settlement of annual tribute

It would also have formed an important part of the Mura community’s financial balance. Also,

Labor service and material provision were recorded in detail and saved for the return of members.

It makes me feel the blood flow more than modern local governments and democracy.

A sequel to yesterday’s construction record.

Construction of this record-breaking residential building began in the spring of 1849.

Since the main production work of community members is agricultural work, rice paddy, rice planting, etc.

It was started before the concentrated spring cultivation season, and after several interruptions during the farming season,

On July 18, 1850, he moved to a “house move”.

The construction period is one year and four months, which is a kind of public works project for the community.

Because it will be completed with this much care

It can be said that the territorial relationship was deeply engraved.

However, the final construction of the main building, “making a tatami room,” took until 1854.

As you can imagine, formal spaces such as tatami rooms have left the consortium of the Mura community.

It may be that each house had a discussion with a carpenter to set up the process.

The carpenter must have decided the period within a certain area and changed the site.

It seems that the schedule was decided at the convenience of the carpenter.

… Building a house in the Mura social community is

There is no doubt that it was a big part of Japanese residential architecture.

As I wrote above, this kind of building process

I think it has settled deeply in Japanese society as a code of conduct.

There are many architectural rituals, but

Looking at this kind of communality, there is a deeply convincing part.

Posted on 4月 14th, 2021 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.