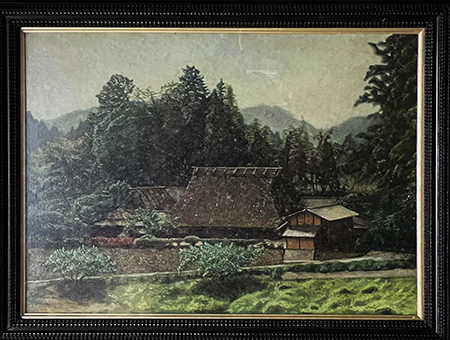

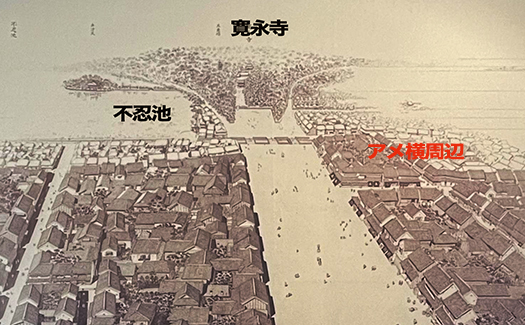

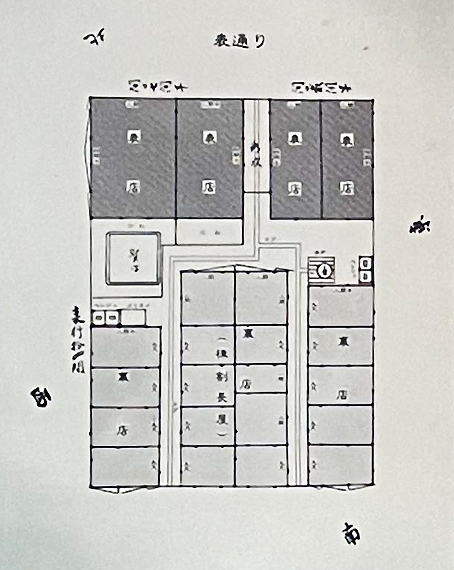

江戸幕府の時代、支配階級・武家大名という存在が社会の基本秩序を構成していた。この奈良県宇陀市近郊に残る片岡家住宅は大名支配の経済の中核的存在。庄屋としてコメ生産の全過程を管理して収穫物を大名家に納税する責任者。そのなかでも片岡家は枢要な存在だったようで本宅に連結して大名自身が逗留するために座敷空間が建てられている。上の写真は、本宅との境界を土壁で仕切っている様子。手前側のニワ空間は農作業のために使われていたようだけれど、この壁から先は大名・本多家のための空間。

住宅建築のデザインというものにはその施主の社会的目的性が顕著に表れる。ここでは武家としての社会存在性を強調する装置化が目指されている。庄屋宅の側に開けられた円窓は、来訪者の素性をいち早く確認するための「偵察」目的だと思える。一種の様式的美化はあるにせよ、用途としては間違いなくそういうもの。基本は軍事に直結する用が形象化されたものだろう。重厚に土塗りされているのは、攻めてくる外敵からの防御性を考えたものか。玄関では当然のように「敷居が高い」。

こちらが主室で、殿様が端座する居室。正面床の間の横の壁は万が一の時の武者の出入り口機能も持っていた。主室で休んでいる大名を奥の「武者だまり」で守護し、万が一の場合には主室に飛び出して大名を守る目的。常在戦場の考え方で、常に外敵襲撃に備える工夫を欠かしていない。

装飾的インテリアとして床の間や掲額、また隣室との境の欄間の木工デザインなどがある。床の間が代表的な装置ということになるけれど、これを背景にして端座することで主人の権威性を装飾することがデザイン上の目的だった。よく殿様の褒め言葉で「床の間での座りがいい」みたいな表現を使う。武家の倫理習慣で家臣たちはこのような座りの良い殿様を中心にして「御恩と奉公」と関係が神聖様式化されていた。

床の間はいごこちがいい、という価値感ではなくいわば「見え」に特化した住宅デザインなのだろう。インテリア全体が「かしこまって敬うべきである」という武家秩序価値感の強制のために奉仕している。

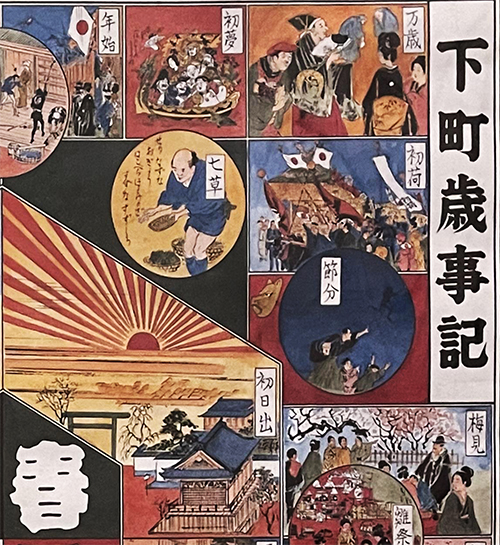

こちらは「次の間」に置かれていた片岡家の庄屋としてのシルシ類。江戸の同心たちが武力的公務を果たすときに「御用」の提灯を見せるのは時代劇のお決まりだけれど、この片岡家のような鄙では公務としての徴米などのシルシとして機能したのだろう。

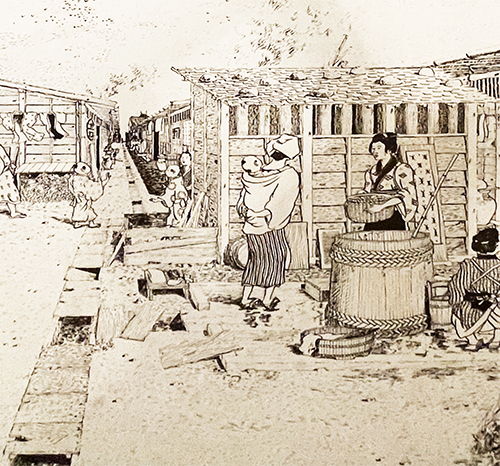

わたしの家系伝承ではこうした庄屋の立場で過ごしていた時期がある。こういう存在は農民と支配者の武家との中間的存在であり、その領主の支配方針、過酷な徴税・増税によって襲撃対象とされることが多かった。領主の非道な政策への怨嗟の標的にされることがしばしば。わが家系ではそうした理不尽の結果、打ち毀しの憂き目にあって、結果として商家へと転身していった経緯がわかっている。この片岡さんの家は比較的に平和だった「譜代」大名家に付属していたので運良く家系が永らえ、このように住宅も残ったのだろうか。

English version⬇

Architectural design for the purpose of showing off power: The Kataoka Family, the feudal lord’s house – 3

Spatial design for the purpose of “visualizing” military rule. The samurai family lived very hard to be seen. …

During the Edo shogunate, the ruling class, the samurai feudal lords, constituted the basic order of society. The Kataoka family residence, which remains here in the suburbs of Uda City, Nara Prefecture, is at the core of the economy of the daimyo ruling class. As headman, he was responsible for managing the entire rice production process and paying taxes on the harvest to the feudal lords. The Kataoka family seems to have been a key player in this process, and a room was built in connection with the main house for the Daimyo himself to stay in. The photo above shows the boundary between the house and the main residence separated by a mud wall. The space in the foreground was used for farming, while the space from this wall onward is reserved for the Daimyo Honda family.

The social purpose of the owner is clearly expressed in the design of a residential building. Here, the house was designed as a device to emphasize the social presence of the samurai family. The round window on the side of the headman’s house seems to be for the purpose of “reconnaissance” to quickly identify the identity of visitors. Although there is a kind of stylistic beautification, this is definitely the purpose of use. Basically, it is a figurative representation of a use directly related to military affairs. The heavily coated earthen walls may have been designed to provide protection against invading foreign enemies. At the entrance, the “threshold is high” as a matter of course.

This is the main room, the living room where the lord would sit on the edge of the room. The wall next to the front alcove also served as an entrance for the warriors in case of emergency. The purpose was to protect the lords resting in the main room by guarding them in the “warrior’s lair” in the back, and to protect them by jumping out into the main room in case of an emergency. With the concept of “Always on the battlefield,” the house was always prepared for attacks by foreign enemies.

Decorative interiors include tokonoma (alcove) and hotofuchi (plaque), as well as the woodwork design of the ranma that borders the adjacent room. The tokonoma is a typical example of such a device, and its purpose in design was to decorate the authority of the master by having him sit on the edge of the room with it as a backdrop. The expression “good sitting in the alcove” is often used as a compliment to the lord. In the samurai family’s ethical custom, the relationship of “gratitude and devotion” was sacredly stylized around such a lord with a good seat.

The tokonoma is not a value of comfort, but rather a house design that specializes in “visibility. The entire interior serves to enforce the samurai order’s sense of value that one should be polite and respectful.

This is the shirushi of the Kataoka family as village headman placed in the “next room. It is a common practice in period dramas to show “Goyo” lanterns when the Edo government officials were performing their official military duties, but in a remote area such as the Kataoka family’s, these lanterns probably functioned as official documents for official duties such as collecting rice.

In my family tradition, there was a time when I spent time in the position of village headman. They were often the target of raids due to the ruling policies of their lords, harsh tax collection, and higher taxes. They were often the target of vindictive attacks against the lord’s outrageous policies. In our family history, we know how the family was struck down as a result of such irrationality, and how the family turned into a merchant family as a result. I wonder if Kataoka-san’s family was lucky to have been attached to a relatively peaceful “Fudai” feudal lord’s family, and thus the family line was able to endure and the house remained as it was.

Posted on 2月 16th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 古民家シリーズ | No Comments »