紙芝居というものは一種のメディアであり、都市環境を必須とする。田舎でも祭りなどのときには出張して上演する紙芝居師もいただろうけれど、ほんの数日間の興業ではその旅費はペイしなかっただろう。紙芝居の「まとめ記事」などを参照すると関東大震災や第2次世界大戦後など、経済社会が崩壊した時期に大量にあふれた失業者たちが、糊口をしのぐ生業として取り組んでいた様子がわかる。

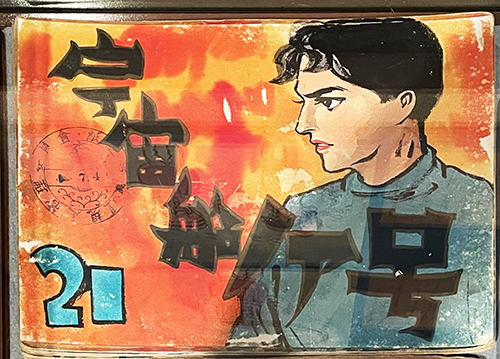

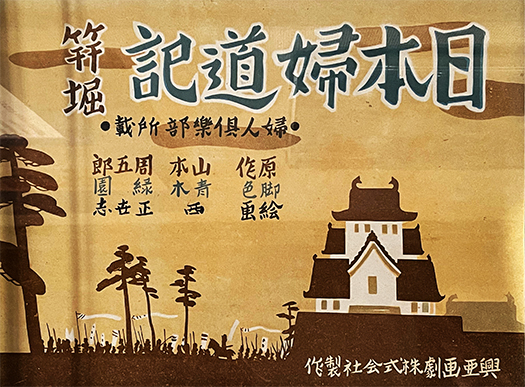

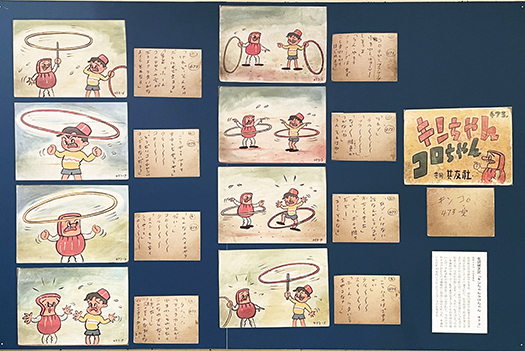

上の写真類は「台東区立下町風俗資料館」展示での紙芝居のテーマ内容のごく一部。こうした形式でのいわば在野の文化活動に対して、行政の側からのさまざまな利用があったとされている。2枚目の写真などは「教育紙芝居」として文科省が関与した題材まであったのだという。また、戦前期にはこどもたちへの軍国教育の一環として政治利用もされていた。日本文化のひとつの波及形式として、このような絵と語りによるストーリー展開形式があって、それが大衆の娯楽文化を形成していた状況が見えてくる。

わたしの接触した時期には、いちばん上のようなSFチックなものや、その後マンガのヒーローの冒険活劇的なテーマが多かったと記憶している。やはり手に汗を握る活劇が、こどもたちの感受性には敏感に「刺さった」のだろう。いかにも教育的なものは自然に敬遠していたと思う(笑)。

こういう形式の初源的なものとしてわたしには「琵琶法師」による平家物語が一番近似的だと思える。琵琶法師という社会的存在は、宗教勢力寺社がその布教と経済活動の一体化された一種のビジネス活動として展開したものとされる。琵琶というめずらしき楽器を演奏しながら、当時の社会の動乱をニュース的に、あるいは演劇的にひとびとに伝承することで日本社会のメディアの嚆矢だったと思える。日々の暮らしに追われる都市居住庶民には政治の極限形態である内戦、源平合戦には大きな影響を受けていただろうけれど、その変動状況についての客観的情報はなかなか伝わらなかっただろう。そういう知識需要をとらえて、京の街の先端的な芸能文化が、メディアの役割を果たし始めたのだと思える。日本の有名寺院には創建説話・縁起などの「絵詞」が多く残っているけれど、それらも法話の伝達手法として機能していた。

もっと遡れば、鎌倉末期に戦災で失われた奈良の東大寺の復元再興にあたって総合プロデューサーだった重源が組織した「勧進」集団による活動が素地であったとも思える。

情報の拡散方法が確立されていない時代、こういった語り部が社会的な需要に対応する存在だったのだろう。そういう社会的需要がわたしの幼少年期にはこの「紙芝居」形式だった。

記憶がだんだんと薄れていくのだけれど、幼少年期にこういう人間くさい紙芝居に接したことで、メディアというものの具体的なイメージを体験したことは間違いがないと思っている。

English version⬇

Japanese Storytelling Culture: Biwa-houshi and Picture Storytelling Postwar Children’s Culture-2

The Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike) and other forms of cultural transmission for the masses were established in Japanese society. It became a means of livelihood for the unemployed during the turmoil. The atmosphere of the postwar black market. ・・・・.

Paper theater is a kind of media that requires an urban environment. Even in the countryside, there were probably some kamishibai performers who traveled to perform at festivals and other events, but their travel expenses would not have paid for themselves if they performed for only a few days. The “summary articles” on kamishibai show business show how the unemployed, who were in great numbers after the Great Kanto Earthquake and the collapse of the economy and society after World War II, were engaged in this business as a means of making a living to survive.

The photos above are just a few of the themes of the picture-story shows on display at the Taito City Shitamachi Museum of Folklore. The second photo even shows an educational picture-story show that the Ministry of Education and Science was involved in. In the prewar period, they were also used for political purposes as part of military education for children. This type of storytelling with pictures and narration was one of the spillover forms of Japanese culture, and it was used to form a popular entertainment culture.

I remember that during the period I was in contact with these stories, many of them were science fiction stories, such as the one at the top of this page, and later on, adventure stories with heroes from manga. I think that the children’s sensitivities were more sensitive to “action” stories that made them sweat and sweat. I think they naturally shunned anything that was too educational (laughs).

The Heike Monogatari in “Biwa-houshi” is the closest I can think of to the origin of this form of drama. The social existence of the biwa priest is said to have developed as a kind of business activity in which the religious power of temples and shrines combined their proselytizing with economic activities. The biwa, a rare instrument, was a pioneer of the media in Japanese society, playing it and passing on the social upheavals of the time to the people in a news or theatrical manner. The common people living in the city, who were busy with their daily lives, would have been greatly affected by the civil wars and Genpei wars, which were the most extreme form of politics, but objective information on the state of change would not have been easily conveyed to them. It seems to me that the cutting-edge performing arts culture of the city of Kyoto began to play the role of media to capture this demand for knowledge. Many famous temples in Japan still have “pictorial scriptures” that contain stories about the founding of the temple and its history, and these also functioned as a method of conveying Buddhist stories.

Going back even further, it seems that the “Kanjin” group organized by Shigen, the general producer of the reconstruction of Todaiji Temple in Nara, which was lost in the war at the end of the Kamakura period, was the foundation of the temple’s activities.

In an age when information diffusion methods had not yet been established, these storytellers must have existed to meet social demand. In my childhood, this social demand was in the form of “picture-story shows.

Although my memory is gradually fading, I am certain that I experienced a concrete image of the media through my childhood contact with these humanistic picture-story shows.

Posted on 2月 20th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: こちら発行人です, 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.