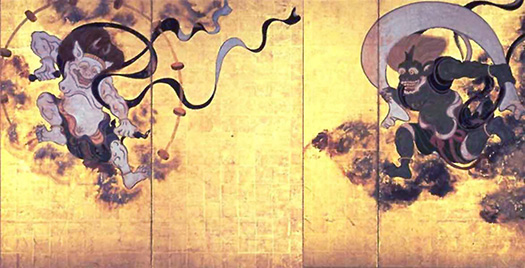

きのうの風神雷神図比較、俵屋宗達と雪舟であります。俵屋宗達は、江戸初期の京都の町人で、ビジネスとしては「扇子」を扱う店舗の主人だったとされる。わたしはとにかくこの人の風神雷神図にぞっこんなのですが、かれの死後、その画業に対して琳派を中興させた尾形光琳がこれまた完全に心酔し、ほぼまったくの複製画を制作した。

江戸期にはながく尾形光琳の作品が風神雷神図の本家のように扱われていたのだという。ほぼ完全にコピーするという所業は、まったく創作人としていかがなものかと思うのが自然だろうけれど、むしろそのリスペクトの末の所業として好意的に伝承されてきた。

日本社会ではこういう行為に対しての懲罰意識というのはそう重視されないのだろうか。琳派というひとつの芸術流派を発展させた光琳に対して、あえてその画業を否定する風潮は起こらなかったのかもしれない。そしてさらに時代が下ると酒井抱一も同様に、今度は尾形光琳の作品をコピーしたとされている。ただ、前出のふたりが京都を活動拠点にしたのに対して、酒井抱一は江戸を拠点にしたので、複製を手本にして制作したとされる。はるかな後世の人間たちの評価としてこの風神雷神という画材テーマのもっとも「創始者」には俵屋宗達が刷り込まれてきていた。

いっぽうでこの雪舟(1420-1506年)は室町時代に活躍した水墨画家・禅僧。俵屋宗達よりもさらに100年近い大先達ということになる。備中国に生まれ京都相国寺で修行した後、大内氏の庇護を受け周防国に。その後、遣明船に同乗して中国に渡り李在という画家から中国の画法を学んだという。

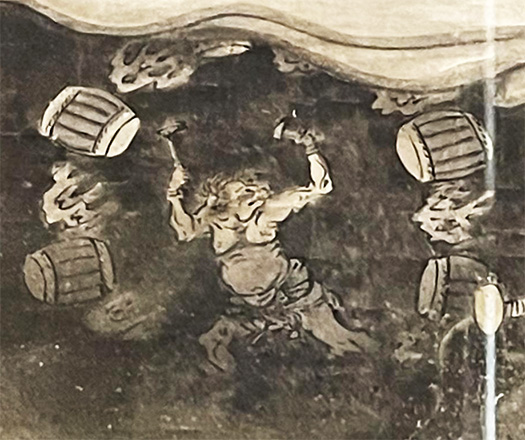

かれが描いた墨絵による風神雷神図を歴史の中から掘り起こした作家・武者小路実篤は「雪舟・雷」というタイトルで雑誌「心」昭和25年8月号で作品を紹介している。

こうした日本の風神雷神画材テーマ化は、平安期 930年7月24日に起こった清涼殿落雷事件(平安京・内裏の清涼殿で起きた落雷災害)が起源とされる。『北野天神縁起絵巻』にこの事件は詳細に描かれた。藤原氏一族の陰謀で太宰府に左遷されて悲憤の内に世を去ってのち、雷神となった菅原道真が自身に無実の罪を着せた藤原氏に天誅を下そうとする場面。壮絶な場面なのに雷神と化した菅公の雷に打たれた殿上人たちが逃げ惑う姿が思わず笑ってしまうようなユーモラスな姿で描かれる。

俵屋宗達は高山寺から絵を依頼されて、このような民衆的な説話や絵巻なども鑑賞して、画題を整理整頓していったのだろう。

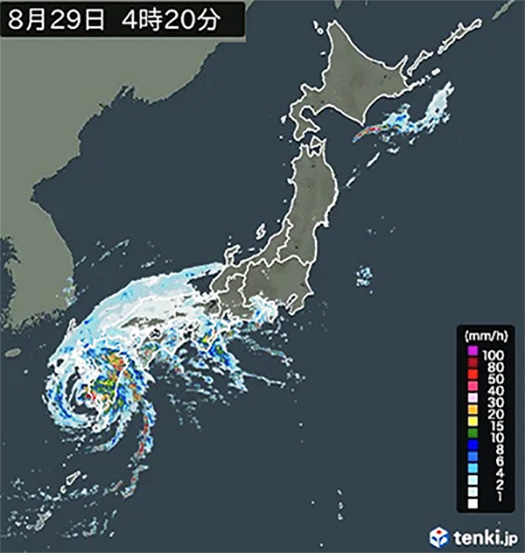

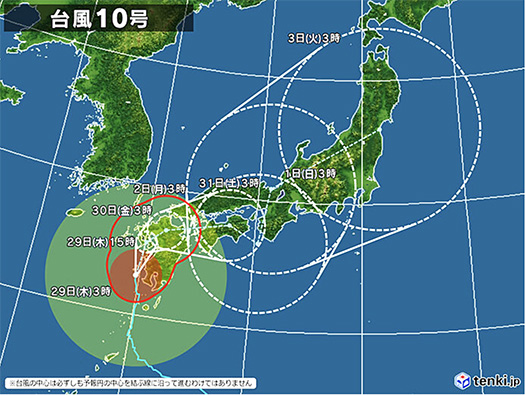

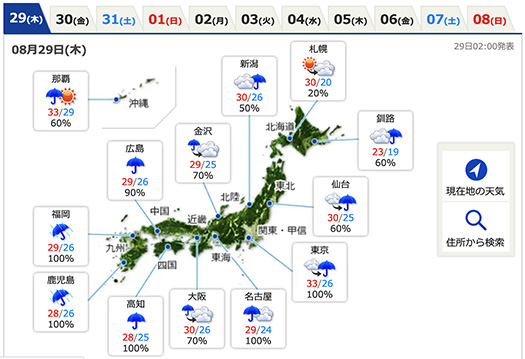

わたし的にはやはり台風に毎年痛めつけられる日本人の伝統的な体験感が、こうした風神雷神テーマを純化させていったように思えてならない。美感といい表現の諧謔性といい、いかにも日本人的な感性を表徴していると思える。

English version⬇

The “God of Thunder” Expression, from the Differences between Sesshu and Sotatsu Tawaraya

Since the Seiryouden lightning incident, wind and thunder gods have been depicted in Japanese society, which coexists with natural disasters. The difference between Sesshu, who learned from Chinese ink painting, and Tawaraya Sotatsu, whose works were popularized by mass society. …

This is a comparison of yesterday’s Wind and Thunder Gods, Sotatsu Tawaraya and Sesshu. Tawaraya Sotatsu was a merchant in Kyoto in the early Edo period (1603-1868), and is said to have been the owner of a store dealing in folding fans. After his death, Ogata Korin, the founder of the Rimpa school, was completely fascinated by his work and made almost exact copies of his paintings.

During the Edo period, Korin Ogata’s works were treated as if they were the originals of the Wind and Thunder Gods. One would naturally think that the act of making a near-perfect copy of an original work of art would not be considered at all creative, but rather, it has been handed down to the next generation as a result of respect for the artist.

I wonder if Japanese society does not place much importance on punitive measures against this kind of behavior. It is possible that Korin, who founded the Rimpa school of art, did not dare to deny his artistic activities. Further down the road, Sakai Hoitsu is said to have copied Ogata Korin’s works as well. However, while the two artists were based in Kyoto, Hoitsu Sakai was based in Edo (present-day Tokyo), so it is believed that he used a copy as a model for his work. In the opinion of later generations, Tawaraya Sotatsu was the “originator” of the wind god and thunder god theme.

Sesshu (1420-1506), on the other hand, was an ink painter and Zen monk active in the Muromachi period. He was a great predecessor of Tawaraya Sotatsu, who lived nearly 100 years before Sesshu. Born in Bicchu Province, he trained at Shokokuji Temple in Kyoto before moving to Suo Province under the patronage of the Ouchi clan. Later, he traveled to China on a Ming Dynasty ship and learned Chinese painting techniques from a painter named Li Jae.

Mushanokoji Saneatsu, a writer who has unearthed from the history of Japan the ink painting of the Wind God and Thunder God by Sesshu Sesshu, introduced his work in the August 1950 issue of the magazine “Kokoro” under the title of “Sesshu, Thunder.

The origin of this Japanese wind god and thunder god thematization has been attributed to the July 24, 930 Seiryouden lightning strike incident (a lightning disaster that occurred at Seiryouden in the Inner Palace of Heian-kyo, Kyoto). The incident was described in detail in the “Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki” (Kitano Tenjin Engi Picture Scroll). In this scene, Sugawara no Michizane, who became the god of thunder after being moved to Dazaifu due to a conspiracy by the Fujiwara clan and passing away in a fit of rage, attempts to bring down the death penalty on the Fujiwara clan that had falsely accused him of crimes. The scene is so humorous that one can’t help but laugh at the sight of the fleeing palace guests who are struck by the lightning of Suga, who has turned into the god of thunder, despite the grandeur of the scene.

Tawaraya Sotatsu was commissioned by Kozan-ji Temple to paint this scene, and he must have viewed such folk tales and picture scrolls to organize the subject matter for his paintings.

I think that the traditional experience of the Japanese people, who are annually battered by typhoons, seems to have contributed to the purification of the Wind God and Thunder God theme. The sense of beauty and the humorous nature of the expression seem to me to represent the Japanese sensibility.

Posted on 9月 2nd, 2024 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »