香取神宮の「奥宮」は荒魂というように言われる。荒魂は神の荒々しい側面、荒ぶる魂である。経津主大神の勇猛果断、義侠強忍等に関する妙用とされる。先日触れた拝殿そして本殿の江戸文化最盛期の爛熟デザインに対して、こちらは古格な神さまの素性を正直に表しているようで、ぐっと心を奪われる。

現在の社殿は、昭和四十八年伊勢神宮御遷宮の折の古材に依るものとされている。式年遷宮による建て替えでの古材がこのように生まれ変わるのは、いかにも古来からの伝承性、魂の継続性を感じさせてくれる。

神々のデザインには好みのようなものがあるのでしょうが、一定の自然豊かな神域を定めて、公園のような環境を作りそこを身分の上下なく自由に参観させる、そしてその背筋を「きよらかにさせる」という民族文化を継続してきていることは、日本の特質なのだと思わせる。

わたし的にはこういう神性に対して、本来の日本人のこころを感じさせられる次第。

周辺環境との調和、全体としての空間デザインマインドというものの日本的コア部分なのではないか。こういうデザイン論が基本的な感受性を支配していると思う。

「荒ぶる魂は邪気を払い霊妙な神気のもと、破邪顕正の働きも活発に開運、厄除け、心願成就のご加護」云々という説明が添えられていて微笑ましい。

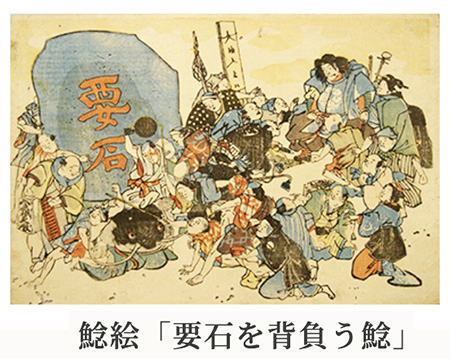

香取神宮にも鹿島神宮同様に「要石」が配置されている。上の写真は「要石を背負うナマズ」の絵図で、この武神が鹿島の神と連携して関東の大地震を押さえつけているのだという(笑)。歴世に渡って関東地域一帯は地震被害が続発していたことを表している。

そうであるからこそ、鹿島も香取も武神が守るという日本的信仰心が育っていったのだとも思える。日本民族にとって関東の地域は大きな開発フロンティアであり、地震多発地帯という困難も抱える中で、利根川東遷などの人為的努力が継続的に投入されてきた。

そのような歴史時間での「民族体験」がこの東国三社のうちの主要2社には込められている。そこからさらにわたしの暮らす北海道の開拓という歴史体験に日本社会は向かっていくことになる。東北地域は「征夷」という対象に挙げられた不幸な歴史を背負って来たけれど、しかし北海道ではそのような経緯はなかった。ただひたすらに寒冷であるという条件に対して、生存環境的進化、住宅性能の向上が不可欠とされた。

ナマズの地震多発地帯という関東フロンティア体験はこうした戯画を生んだけれど、さて北海道の高断熱高気密住宅創造体験からは、どんな戯画化が生成していくだろうか。

いまのところ、北海道神宮にはそのような民族体験の形象化は見られないけれど(笑)。

English version⬇

Katori Jingu Shrine (6): Exploring the Three Shrines of Eastern Japan – 20

The space is an architecturally designed representation of the fierce spirit of the god of worship, Kyotsu-no-okami. The construction materials are recycled from the old materials used for the ceremonial relocation of the Ise Jingu Shrine. It is a very “Arakotama” (spirit). The building is designed by the architect, Mr. K. Kikuchi, who is also the director of the building.

The “Okumiya” of Katori Jingu Shrine is said to be called Arakotama. Arakotama is the wild side of God, or the soul that rages. It is said that it is a strange symbol of the god Kyotsu-no-okami’s valor, chivalry, and perseverance. In contrast to the mature design of the hall of worship and the main hall of the shrine, which I mentioned the other day, this shrine seems to honestly express the nature of the ancient god, and is captivating.

The present shrine pavilions are said to have been built using old materials from the Ise Jingu Goshengu in 1973. The fact that the old timbers were used for the reconstruction of the shrine during the ceremonial relocation of the Ise Jingu shrine gives one a sense of the continuity of the ancient tradition and spirit of the shrine.

Although there may be some preferences in the design of deities, the fact that Japan has continued to maintain a national culture of designating certain nature-rich sacred areas and creating park-like environments where people of all ranks are allowed to freely visit, and where people’s backs are made to stand upright, makes me think that this is a characteristic of the Japanese people.

In my opinion, this kind of divinity makes me feel the true spirit of the Japanese people.

I believe that this is the core of the Japanese mindset of spatial design as a whole, in harmony with the surrounding environment. I believe that this kind of design theory dominates the basic sensitivity.

The explanation that “the souls of the wild spirits are under the influence of a mystical spirit that dispels evil spirits, and the work of breaking evil and manifesting righteousness is also active to bring good luck, ward off bad luck, and fulfill one’s desires” is very funny.

Like the Kashima Jingu Shrine, the Katori Jingu Shrine also has a “keystone” in place. The photo above is a drawing of a “catfish carrying a keystone,” and it is said that this warrior god is holding back a major earthquake in the Kanto region in cooperation with the god of Kashima (laugh). It represents the fact that the Kanto area and its vicinity had suffered a series of earthquake damage over the past generation.

It seems to me that this is why the Japanese belief that the god of war protects both Kashima and Katori grew up. For the Japanese people, the Kanto region was a great development frontier, and human efforts, such as the eastward shift of the Tone River, were continuously invested in the region, despite the difficulties of being an earthquake-prone area.

The “ethnic experience” of such a historical period is contained in these two major shrines of the Three Eastern Provinces. From there, Japanese society will further move toward the historical experience of the development of Hokkaido, where I live. While the Tohoku region has had the unfortunate history of being singled out as the target of “barbarian conquests,” this was not the case in Hokkaido. The cold conditions of the region made it essential for the evolution of the survival environment and the improvement of housing performance.

The Kanto frontier experience of earthquake-prone catfish has given rise to such caricatures, but what kind of caricatures will be generated by the experience of creating highly insulated and airtight housing in Hokkaido?

At the present time, we do not see such a caricature of ethnic experience in the Hokkaido shrine (laugh).

The explanation that “the souls of the wild spirits are under the influence of a mystical spirit that dispels evil spirits, and the work of breaking evil and manifesting righteousness is also active to bring good luck, ward off bad luck, and fulfill one’s desires” is very funny.

Posted on 8月 25th, 2023 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.