江戸末期には総勢150名ほどの当主の葬儀を営むほどの商家だったものが、幕末-維新の政治的大変動の中で翻弄され家運の衰退を招き、そこからの逆転を目指して渡道という決断に至った。武家社会とは違うけれど、江戸期商家のひとつの典型例のようにも感じられる。

そういう社会状況に遭遇した幕末維新期の曾祖父が書き残した「漢詩」〜商家から農業に転身する心事を表現〜は、わたしが3歳まで過ごした北海道岩見沢市郊外の家の欄間に掲げられていたという。

その漢詩掲額はいまは行方がわからない。しかし確かな「記憶」が兄たちには残っている。ぜひ、この時期を生きた曾祖父の肉声をその漢詩から感じたい・・・。

東作、というのが曾祖父の名。わが家に残る戒名には「戒」という文字が付されている。戒める、という内意の字であることから、その生き様の探究や記録をためらったと感じさせられる。

その背景としてはたぶん政治的なものがあったのではないか、という推測。

1831年から1883年までの52年間の生涯。1862年の決定的な参勤交代制度の終了時期かれは31歳。そして倒幕に至る福山藩にとってのメルクマールである第2次長州征伐の敗戦は1866年・34歳時期。そこから8年後42歳の時期に商家から農家に転身したことになる。

曾祖父は、家系が深くビジネスに関与する本陣宿・今津の18kmほど隣りの宿駅、神辺宿生まれの福山藩の儒学者・菅茶山が創設した、民間人向けの郷塾「廉塾」(上の写真)に学んだようなのです。この塾には幕末の過激な勤皇の志士たちの精神的バックボーンとされた「頼山陽」も学んだ。

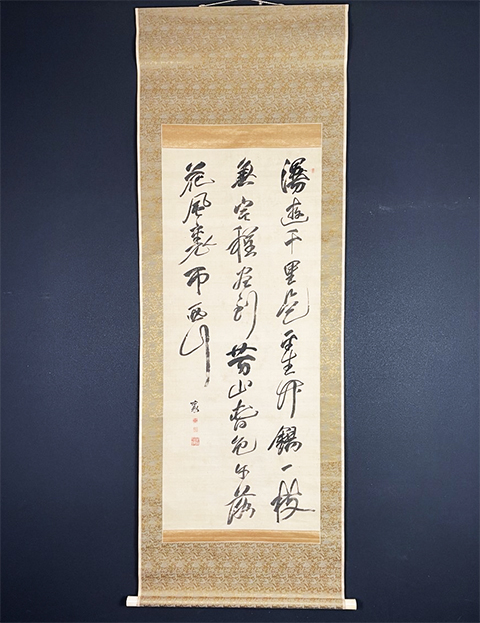

頼山陽は今津宿にも宿泊経験があったようでわが家系には「頼山陽の書」があった。上の写真はWEB上で古文書を取引するサイトにあった頼山陽の書。

その同じ塾に学んだ経験があり、しかも自分の子どもに「美之三郎」と名付けている。この命名は頼山陽の子の「頼三樹三郎」〜安政の大獄事件で刑死の過激思想家〜に心情的にあやかったようなのです。

幕末期の開国を指揮した老中・阿部正弘を輩出した徳川家「親藩」でありながら官軍・長州軍に降伏姿勢を見せ、さらに最終的な箱館戦争では反乱軍鎮圧部隊を派遣している。精神と肉体の「引き裂かれた」ような政治軍事行動。この時期の藩の政治軍事の経緯が、曾祖父の事跡から想像させられる。

経済的な破綻だけでなく「藩に忠実な商家としての立場」と「廉塾で学んだ勤皇思想」との間で、激しい精神的な「引き裂かれ」を経験していたのではないだろうか。

その思想と、家業を捨て土に還る心事を表現したものが欄間の「漢詩」なのか?

なんとかその残像を探したい。・・・

お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

The Loyalist Ideology of Merchant Heads During the Bakumatsu-Meiji Restoration Period and Their Transition to Agriculture

The loyalist ideology connecting Fukuyama Domain’s Confucian scholar Suga Chazan and his student Rai Sanyo. Did the turbulent political climate create a “torn” state of mind for merchant heads? …

By the late Edo period, this merchant house had grown large enough to hold funerals for its head family members, numbering around 150 in total. Yet, caught up in the political upheavals of the Bakumatsu and Meiji Restoration, it was buffeted by change and faced decline. Seeking a reversal of fortune, the family made the decision to relocate to Hokkaido. While different from the samurai world, this feels like a typical example of an Edo-period merchant house.

The Chinese poetry my great-grandfather wrote during this turbulent Bakumatsu-Meiji Restoration period—expressing his feelings about transitioning from merchant to farmer—was hung on the transom of the house in the suburbs of Iwamizawa City, Hokkaido, where I lived until age three.

That framed poem is now lost. But my brothers retain a vivid “memory” of it. I long to sense my great-grandfather’s own voice through those Chinese poems, voices from the era he lived…

His name was Tōsaku. The posthumous Buddhist name preserved in our family includes the character “戒” (kae), meaning “to admonish.” This suggests a hesitation to explore or record the details of his life.

I suspect political reasons likely lay behind this.

His life spanned 52 years, from 1831 to 1883. He was 31 when the decisive end of the sankin-kotai system came in 1862. The defeat in the Second Chōshū Expedition, a watershed event for the Fukuyama domain leading to the overthrow of the shogunate, occurred in 1866 when he was 34. Eight years later, at age 42, he transitioned from a merchant family to a farming household.

His great-grandfather studied at the Renjuku private school (pictured above), founded by Suganayama, a Confucian scholar from the Fukuyama domain. Suganayama was born in the post station of Kanbe, about 18 km from Imazu, a post station deeply involved in the family’s business. This school was also attended by Rai Sanyo, whose writings became the spiritual backbone for radical imperial loyalists in the Bakumatsu period.

Rai Sanyo also stayed at Imazu-juku, and our family possessed a “Rai Sanyo calligraphy piece.” The photo above shows Rai Sanyo’s calligraphy found on a website trading ancient documents.

Having studied at that same school and naming his own child “Minosaburo,” This naming choice seems to have been emotionally inspired by Rai Sanzaburō, the son of Rai Sanyō—an extreme ideologue executed during the Ansei Purge.

Though part of the Tokugawa clan’s “pro-shogunate” branch that produced Abe Masahiro, the senior councilor who led the opening of the country in the Bakumatsu period, they showed a posture of surrender to the imperial forces and the Chōshū army. Furthermore, in the final Battle of Hakodate, they dispatched troops to suppress the rebel forces. A political and military stance that seemed to “tear apart” spirit and flesh. The domain’s political and military trajectory during this period can be imagined through my great-grandfather’s deeds.

Beyond mere economic collapse, he likely experienced a fierce spiritual “tearing apart” between his “position as a merchant loyal to the domain” and the “imperial loyalty ideology learned at the Renshu Academy.”

Could the Chinese poem on the transom be an expression of that ideology and his resolve to abandon his family business and return to the earth?

I long to somehow trace its lingering echoes…

Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 11月 27th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.