わたしたちは現代の資本主義制度という社会システムのなかに生きている。そしてそれは人類史の進展過程で考えても、ごく合理的な社会制度だと思える。市場経済と政治の民主主義は根本的合理性がある。

この制度は欧米では市民社会が「戦い取った」歴史であり、日本では明治維新という政治経済社会の急進的大革命によって成立した。いまでは空気のように感じられることが、しかし江戸期ではそうではなかった。

幕末期(1850年代)の推定人口約3,200万人の中で武士は約190万人、つまり約6%を占めていた。この「働かない」階級に対して他の人びとはさまざまな税や貢物を強いられる。生産性が低い社会でこれは桎梏。そういった連中が政治軍事の決定権を持ち、経済社会をも支配し(ようとし)ていた。かれらにはまっとうな経済感覚は持てなかった。しかし社会の意思決定はかれらの専権だった。

このギャップのなかで社会はさまざまな苦悩を体験する。家系の歴史をごく平明に理解したいと思ってみるとこの「闇」がどうしても深く差し掛かってくる。逆に、そういう社会背景の中でいろいろ苦悩したのでしょうね、という納得が浮かび上がって来る。その苦悩の中から社会の進歩の起動力は生まれ出てくる。

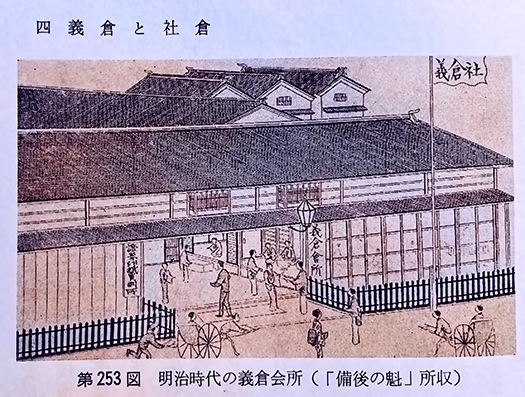

そういう光明のような江戸期の社会システムのひとつとして「義倉・社倉」がある。これは飢饉や災害に備えて穀物を貯蔵した倉庫制度。統治機構が富裕層からの寄付などによって穀物を集め、非常時に窮民に支給する仕組みとして運用されていた。

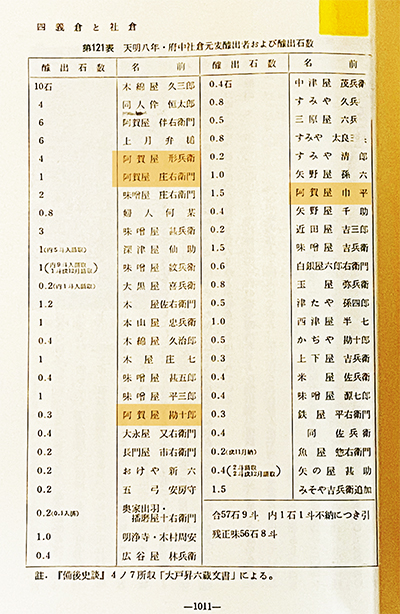

図は福山藩領でのこの義倉の会所建築と「府中」地域における社倉への出資者名簿。この地域に密着していた商家たちの名前と米穀の出資状況が明示されていて興味深い(福山市史より)。なかにわたしの家系が屋号とした「阿賀屋」の地域商人の名もある。

合計で57石あまりとの記載。石という単位は基本的に1人の人間が1年間に食するコメの総量を示す。またこれだけの建築(明治期に描かれたもの)が、その出入り状況も含めて証明されている。

義倉にはコメが貯蔵されるとともに飢饉発生時以外の通常時には、その「資本」が商人層に貸し付けられ、その運用金利が重要な収入源とされた。一種の「銀行機能」でもあった。

江戸期商家のわが家系の多面な様子がうかがい知れる。義倉・社倉への出資はわが家系を含む商家層が、武家社会の闇のなかで「経済力で社会的責任と金融機能を担っていた」証明。しかしこの公的制度協力者であった商家は、その後の幕末の経済混乱期において「藩に協力して貯めた現銀を藩札と交換され、その藩札の崩壊によってすべてを失う」という、過酷な運命を辿ったことになる。・・・

お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Merchant Class Contributions to Edo Period Social Welfare “Gikura”】

Human society evolves gradually. As darkness and light intertwine, each lineage continues to experience its own rise and fall. …

We live within the social system of modern capitalism. And even considering the progression of human history, it seems a highly rational social system. Market economies and political democracy possess fundamental rationality.

This system represents a history “fought for” by civil society in the West, and in Japan, it was established through the radical political, economic, and social revolution known as the Meiji Restoration. What now feels as natural as the air itself was not so during the Edo period.

In the late Edo period (1850s), samurai numbered about 1.9 million out of an estimated population of 32 million—roughly 6%. The rest of the population was forced to pay various taxes and tributes to this “non-working” class. In a low-productivity society, this was a shackle. These individuals held political and military decision-making power and dominated (or sought to dominate) the economic and social spheres. They lacked sound economic sense. Yet societal decision-making was their exclusive prerogative.

Within this gap, society experienced profound suffering. When attempting to understand family history in plain terms, this “darkness” inevitably looms large. Conversely, one comes to understand that such suffering likely arose from this very social backdrop. It is from this suffering that the driving force for societal progress emerges.

One such beacon of light within the Edo period’s social systems was the “Gikura/Shakura” (public granaries). This was a warehouse system for storing grain in preparation for famines and disasters. The governing body collected grain through donations from the wealthy and operated it as a mechanism to distribute grain to the destitute during emergencies.

The illustration shows the meeting hall architecture for this gokura system within the Fukuyama domain and a list of contributors to the shakura in the “Fuchu” area. It’s fascinating to see the names of local merchants deeply rooted in this region and their grain contributions clearly listed (from the History of Fukuyama City). Among them is the name of the local merchant “Aga-ya,” the house name used by my own family lineage.

The total recorded is over 57 koku. The unit “koku” fundamentally represents the total amount of rice consumed by one person in a year. Furthermore, the existence of this building (depicted in the Meiji period) and its operational activities, including transactions, are documented.

The gokura stored rice, but during normal times outside of famines, this “capital” was lent to the merchant class. The interest earned from these loans served as a significant source of income. It also functioned as a kind of “banking system.”

This offers a glimpse into the multifaceted nature of my family’s merchant house during the Edo period. Investment in public granaries and shrine granaries proves that the merchant class, including my family, “shouldered social responsibility and financial functions through economic power” within the shadows of samurai society. However, these merchant families, who had cooperated with the public system, faced a harsh fate during the subsequent economic turmoil of the Bakumatsu period: “The silver they had stored in cooperation with the domain was exchanged for domain notes, and they lost everything when those notes collapsed.” …

Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 11月 28th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.