幕末〜明治初期のわが家系の時間差探訪。商家として江戸期の社会に適合して生存戦略を立て、瀬戸内海地域の「松永」での塩業とその流通商家として尾道の「阿賀屋」株を入手し、同時に大名の参勤交代に伴う「本陣」ビジネスにも関与していた様子がわかってきた。

そこからその当時の世相と実態をいろいろな手段で掘り下げようとするけれど、どうしても貨幣経済が完全に行き渡った現代の価値観をメガネにしてしまう。調べるほどに家系の出処進退と当時の社会の実相との整合性の解明が求められるのだ。

わが家系は1873(明治6)年ころに福山市今津・松永地域から移転し、芦田川の内陸側、福山市中心部から約5kmほどの親戚が多く住む「中津原」地域で農業に入っている。当時の当主は1831年生まれで、若年期には本陣ビジネスで接触する大名家との接遇にインテリ的対応が可能なように学問に励んでいた。この1873年・42歳時の農業転身に際し勤皇系の当時のインテリらしい「漢詩」を詠んだりもしている。

江戸期の「参勤交代」に伴う本陣ビジネスは1862年頃には破綻しているので、その時期から11年で当時の当主は、家業であった商家ビジネスを見切ったことになる。どういった背景事情があったのか。

まず第1に、本陣ビジネスでの大名家からの支払は果たして現銀だったのか? これは調べるまでもなく経済的に破綻している多くの藩は「藩札」で決済していたに違いない。藩士への俸禄すら藩札で賄っていたとされるのだ。1871(明治4)年に廃藩置県となったが、多くの藩主はそのことを領地を奪われると受け止めるより「藩札の決済から逃れられる」と歓迎したとされるのだ。この年には福山藩・今津では藩主が東京に「華族」として移転することに抗議する暴動一揆が起こっている。「バカヤロー、責任を取れ!」

さらに第2に、明治の政変前後の時期には異常な物価高騰が起こっている。1859(安政6)年から1867(慶応3)年までの8年間で物価は匁建て(銀貨基準)で約6.6倍になったとされる。それに対して各藩から藩札の価値保全責任を継承した新政府の決済率は、ほぼ6〜7掛け程度だったと言われる。弱り目にたたり目。

こういう経済の実態推移を考えれば、江戸期商家を承継した家系の当主が農業への転身を図ったのは、ごく自然なことだと腑に落ちてくる。そしていまは亡き伯父の家に残っているその達筆としずかに相対したいと思っている。〜この項、つづく。

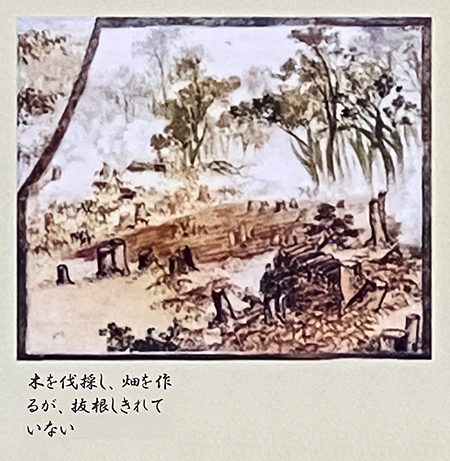

<写真とイラストは北海道・八雲に開拓入植した尾張徳川家藩士たちの復元家屋と土地状況>

お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

The Collapse of Domain Currency and Hyperinflation That Struck Late Edo-Period Regional Merchants

The de facto end of the sankin-kotai system in 1862. Prices rising 6.6 times over the next eight years. The economic foundation crumbled. The family shifted to farming in their ancestral lands. …

A journey through the time gaps of my family lineage from the late Edo period to the early Meiji era. As a merchant family, we adapted to Edo-period society and devised survival strategies. We engaged in the salt industry in the Setouchi region under the name “Matsunaga” and acquired shares in the Onomichi-based ‘Agaya’ company as a salt distribution merchant. Simultaneously, we were involved in the “honjin” lodging business associated with daimyo feudal lords’ mandatory alternate attendance at the shogun’s court.

I strive to delve into the social climate and realities of that era through various means, yet inevitably view it through the lens of modern values shaped by a fully monetized economy. The more I research, the more I feel compelled to clarify the alignment between my family’s rise and fall and the true nature of society at that time.

My family lineage relocated around 1873 (Meiji 6) from the Imazu and Matsunaga areas of Fukuyama City. They settled in the Nakatsuhara region, located inland along the Ashida River, about 5 km from central Fukuyama City, where many relatives lived, and took up farming. The head of the household at that time was born in 1831. During his youth, he diligently pursued learning to ensure he could handle interactions with the daimyo families encountered through the honjin business with an intellectual demeanor. Upon this agricultural transition in 1873, at age 42, he composed a “Chinese-style poem” characteristic of the pro-imperial intellectuals of the time.

The honjin business associated with the Edo period’s sankin-kotai system had collapsed around 1862. Thus, within 11 years of that collapse, the head of the family had abandoned the merchant business that had been the family trade. What were the circumstances behind this?

First, were payments from daimyo families for honjin services actually made in silver? This hardly needs investigation; many financially bankrupt domains undoubtedly settled accounts using domain-issued paper money. It’s said even samurai stipends were paid in such paper currency. When the abolition of the han system and establishment of prefectures occurred in 1871 (Meiji 4), many feudal lords reportedly welcomed it not as a loss of territory, but as an escape from settling debts with han notes. That same year, in Fukuyama Domain’s Imazu, riots erupted protesting the feudal lord’s relocation to Tokyo as a “noble.” “You bastard! Take responsibility!”

Second, an abnormal surge in prices occurred around the time of the Meiji Restoration. Over the eight years from 1859 (Ansei 6) to 1867 (Keio 3), prices are said to have risen approximately 6.6 times based on the monme standard (silver coin basis). In contrast, the settlement rate of the new government, which inherited the responsibility for maintaining the value of domain notes from the various domains, is said to have been only about 60-70% of the original value. Adding insult to injury.

Considering these economic realities, it makes perfect sense that the head of a family inheriting an Edo-period merchant house would seek to transition into agriculture. And now, I find myself wanting to quietly confront that beautiful calligraphy still preserved in my late uncle’s house. ~This section continues.

Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 11月 26th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.