わたしはクルマ移動一択で、ほとんど札幌地下鉄などを利用しないライフスタイルで生きてきました。そういうことで、札幌市が「敬老パス」という制度を取り入れ、高齢者におトクな割引料金制度を提供しているという情報にすっかり無関心でいた。

で、前回1ヶ月前8/15に「ワクワク」という記事投稿したのですが、やはりこれまでのライフスタイルに不整合なのでなかなか利用する機会はやってきてくれない。というか、「あ、そうだ」と思いつかないとどんどんスルーしてしまうのですね。

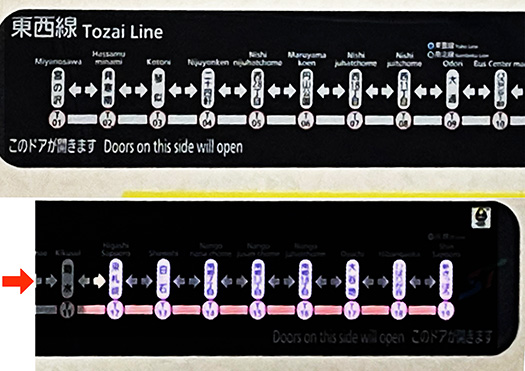

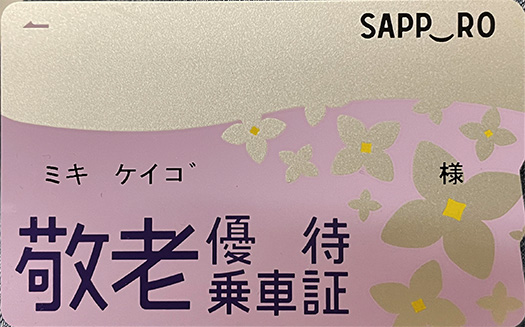

ということで一昨日、ある要件で札幌地下鉄の「東西線」で西の果てから3駅目である「琴似駅」から合計15駅目の東方地点の「ひばり野」駅まで意を決して利用させていただきました。その結果でようやく昨日時点までで利用したのは、合計で2,000円弱(実費で200円)であります。1,000円で入手した10,000円の券面のうちようやく1/5が消化出来た次第。なかなか利用は進まない。

なんですが、さすがに15駅の移動はなかなかで時間は30分ほど。往復利用で1時間超。移動歩行(最大の狙いは実はこれ!)を含めて約1.5〜2時間。ながらく「自宅兼用」の仕事環境にどっぷりとハマっていて、現代人にほぼ一般的な「通勤地獄」を忘却した人生だったのだと思い至る時間。〜行きは昼前後の時間で帰り時間が夕方6時前後と少し退勤時間に掛かった程度。みなさんの労苦の足許にも及びません。

そういえば東京での会社勤務時代はエラかったなぁと人生回想・・・。

ということでしたが、まだまだ敬老パス「追加購入」まで至りません。できればJR線にも適応してくれれば、とは思うのですが、ムリなのでしょう、いろいろ事情は理解できる。

自分で考えてみて、日常的な移動手段を転換するというのは意識チェンジが難しい。わたしは札幌市内よりもそれ以外との交流の方がはるかに大きいということも再認識。札幌市内中心部に行くのは非常にレアで、むしろ新千歳空港〔タウン)の方がはるかに日常感覚に近い。新千歳空港の駐車場が大幅値上げする超混雑状況だそうですが、たしかに臨空ゾーンの社会的ウェートは比重が高まっていくでしょうね。

しかしせっかくの特典。なんとか健康・歩数稼ぎの移動手段として、大いに活用したいです。

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Using the Senior Citizen Pass ♬ A 1.5-Hour Round-Trip Journey Through Sapporo】

A wonderful service for seniors. Trying to use it creates mismatches in daily routines. I’ll figure out how to make it work and increase opportunities for walking for my health. …

I’ve lived a lifestyle where driving is my only option for getting around, hardly ever using the Sapporo subway or similar transit. Because of that, I was completely oblivious to the fact that Sapporo City had introduced a system called the “Senior Citizen Pass,” offering discounted fares for the elderly.

Then, about a month ago on August 15th, I posted an article titled “Exciting News.” But since it didn’t really fit my lifestyle, I never really had a chance to use it. Or rather, unless I suddenly thought, “Oh, right,” I just kept forgetting about it.

So, the day before yesterday, for a specific errand, I finally resolved to use the Sapporo Subway Tozai Line. I rode from Kotoni Station, the third station from the western terminus, all the way to Hibarino Station, the 15th station eastward. As a result, my total usage up until yesterday amounted to just under 2,000 yen (200 yen out of pocket). I’ve finally used up 1/5 of the ¥10,000 face value I got for ¥1,000. Progress is slow.

Still, traveling 15 stations took about 30 minutes. Round trip was over an hour. Including walking (which was actually the main goal!), it took about 1.5 to 2 hours. It made me realize how deeply immersed I’d been in my “home-office hybrid” work environment, forgetting the “commuting hell” that’s almost universal for modern people. ~My departure was around noon, and my return was around 6 PM, slightly overlapping with the evening rush hour. It’s nothing compared to everyone else’s struggles.

Come to think of it, my corporate days in Tokyo were pretty tough… reminiscing about life…

That said, I’m still not quite at the point of needing to buy an additional senior citizen pass. I wish it could be used on JR lines too, but I understand it’s probably not feasible given the circumstances.

Thinking about it myself, changing your daily transportation habits requires a significant shift in mindset. I’ve also realized again that my interactions outside Sapporo far outweigh those within the city. Going to central Sapporo is extremely rare; in fact, New Chitose Airport (Town) feels much more like my daily reality. I hear New Chitose Airport’s parking is extremely crowded with a significant price hike. Indeed, the social weight of airport zones will likely grow heavier.

Still, it’s a valuable perk. I want to make the most of it as a means to boost my health and step count.

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha.

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 9月 18th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類 | No Comments »