さて昨日の続きですが、商標登録のWEB申請、なかなか時間が掛かる・・・。

実はあしたから所用で関西圏に行くのでさまざまな取材行脚も並行したいと思います。当然、広島県福山や尾道などにも足を伸ばしたい。レンタカーであちこち探索、予定満杯気味。

一方、このブログを見てくれている知人からときどき有益な情報が寄せられます。

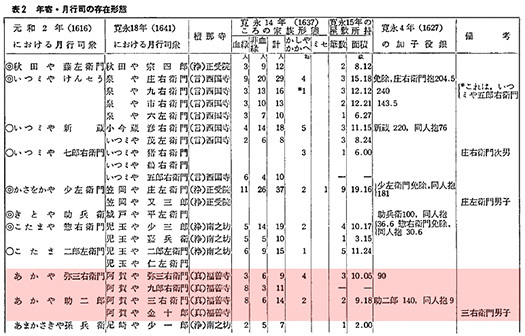

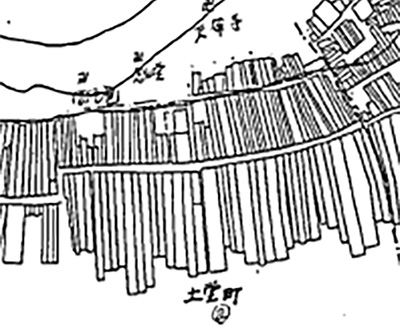

上図は広島大学の中山富廣先生の論文で「近世初期の尾道における商品流通」をご案内いただいた。そこに「尾道阿賀屋」の人物名が出ていた。江戸期瀬戸内海交易の心臓部・尾道では、商家による「自治組織」が運営され、その名簿のなかに出ていた次第。下は間口が間口が狭く奥行きが長い江戸期「商都・尾道」の街割り図。

「あかや」と記されているのがわが家系がその一員になっていた「阿賀屋」で、1616-1641年当時の自治組織の「月行司衆」になっている。有力商人であるかれらは「加子役銀」という公費負担を出資している。これは港町の港湾労働に従事する人びとへの労務費などが主な用途のおカネ。阿賀屋は2名が役に就いていて10.5%の加子役銀負担割合。

この探索を本格化させるまで江戸時代にはそれほど深い興味を持っていなかったのですが、コメ経済幕藩体制のなかで次第に「市場経済」が浸透拡大していったのだと気付くようになった。わたしの家系は1718年の亨保の百姓一揆で打ち毀しにあって米作経済の現地代官的な庄屋層から脱落して以降、松永で塩業経営にシフトして、さらにこのような阿賀屋の商家株を入手したことで市場経済型の自治独立的な生き方に向かって行ったと言える。

興味深いのは「檀那寺」記載で浄土真宗の「福善寺」と。この宗派と阿賀屋という名前から播州の「英賀」との関連性が強く印象づけられる。秀吉によって英賀城が落城した後、播州からこの地に人びとが大量移住したとされ、そのまとめ的な寺院が福善寺。英賀は本願寺門徒の宗教勢力として知られ、阿賀屋も三木氏なのでその関係性はあきらか。一時期はわたしの家系についてこちらなのだとすっかり信じていた。

で、表には「家族形態」記述もあり血縁と非血縁の仕分け人数が明記。血縁を基盤とする中小企業的。

さらに、1638年の「屋敷所持」項目もあり、9-10畝(1畝は約30坪)なので各300坪ほどの屋敷地を所有していた記載も。そういう屋敷に9-14人程度が暮らしていた。

う〜む、生活ぶりにまでズームイン感(笑)・・・

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Edo Period: Merchant Houses in Onomichi Forming “Self-Governance Organizations”】

Merchant houses bearing the name “Aka-ya” from the Edo period were involved in managing the autonomous region and the Seto Inland Sea trading city. Was this the forefront of Japan’s transition to a market economy? …

Now, continuing from yesterday, this online trademark registration application is taking quite a while…

Actually, I’ll be heading to the Kansai region tomorrow for some business, so I plan to conduct various interviews while I’m there. Naturally, I also want to visit places like Fukuyama and Onomichi in Hiroshima Prefecture. I’ll be exploring all over by rental car, and my schedule is getting pretty packed.

On the other hand, I occasionally receive useful information from acquaintances who read this blog.

The image above is from a paper by Professor Tomihiro Nakayama of Hiroshima University, introducing “Commodity Distribution in Onomichi during the Early Modern Period.” It mentioned the name “Onomichi Aga-ya.” In Onomichi, the heart of Seto Inland Sea trade during the Edo period, merchant families operated an “autonomous organization,” and this name appeared in its membership roster. Below is a street layout map of Edo-period “Onomichi, the Commercial Capital,” characterized by narrow frontages and deep lots.

The location marked “Akaya” is the “Aga-ya” where my family lineage was a member. It was part of the autonomous organization’s “Tsukigyoji-shu” during the period 1616-1641. As influential merchants, they contributed to the public fund known as “Kashiyaku-gin.” This money primarily funded labor costs for port workers in the harbor town. Two members of the Aga-ya held positions, bearing a 10.5% share of the Kashi-yaku-gin burden.

Before delving deeply into this research, I hadn’t held such a profound interest in the Edo period. However, I came to realize that within the rice-based feudal system, a “market economy” gradually permeated and expanded. My family lineage, having been crushed in the 1718 Kyōhō Peasant Uprising and thus falling from the local daikan-like village headman class in the rice-farming economy, shifted to salt production management in Matsunaga. Subsequently, acquiring shares in a merchant house like Aga-ya allowed them to move towards a market economy-based, autonomous, independent way of life.

What’s interesting is the “temple patronage” record listing the Jōdo Shinshū temple “Fukusen-ji”. This sect and the name “Aga-ya” strongly suggest a connection to “Ega” in Harima Province. After Hideyoshi captured Ega Castle, large numbers of people are said to have migrated here from Harima, with Fukusenji serving as their central temple. Both Ega and Aga-ya were associated with the Miki clan, making the connection clear. For a time, I fully believed this was the origin of my family lineage.

Furthermore, the front page includes a “Family Structure” description, clearly listing the number of blood relatives and non-blood relatives. It’s like a small family business based on blood ties.

Additionally, there’s a “Residence Ownership” entry from 1638, stating they owned 9-10 acres (1 acre is about 30 tsubo), meaning they had about 300 tsubo of land per residence. Around 9-14 people lived in such residences.

Hmm, it feels like we’re zooming in on their lifestyle (lol)…

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 12月 18th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.