日本の文章・文学というのは、中国大陸からの「漢字」文化の導入という最大のエポックを経験して以降、もともと発語されていたに違いない「やまとことば」との統合が主要な発展経緯だっただろう。古事記・日本書紀の編纂という文化大事業が「国家事業」として取り組まれてきた。

そのプロセスで「ひらかな・カタカナ」が創案されていったことは日本独特の咀嚼文化の事始めとして、社会全般あらゆる事象で後世までインパクトを与え続けた。「柔軟に受け入れ、独自に使いやすく変容させる」ということが「日本らしさ」とも言えるのだろう。

明治以降、この特質が対西洋文明に対して発動され急速な近代化・現代化が可能になった。ただし日本語としては江戸期までの対中華圏文化に対してよりカタカナの活用が強化され、日本的な韻文余韻文化・五七調から科学的明晰化・散文重視に大きく方向性が変化した。韻文余韻重視「文学」から離陸していったのだと言える。

芭蕉が生きていたのは江戸時代前期。韻文余韻表現の先人として平安末期〜鎌倉初期の西行に、強く惹かれていたことがあきらか。この奥の細道行はたぶん芭蕉のなかでは西行が詠んだ平泉にまつわる五七調表現をカラダで実体験したいということが目的だと想像できる。

とりわきて 心もしみて 冴えぞわたる 衣河みにきたるけふしも

ききもせず たばしねやまのさくら花 よしののほかに かかるべしとは (西行・山家集)

西行(1118-1190)がこの地を訪れた時代は奥州藤原氏全盛の時代。西行は平泉を2度訪問。1度目は20代後半で目的は100年以上前の歌人・能因法師が訪れたみちのくの歌枕(和歌にちなんだ地名や名所)を実際に巡ること。このとき奥州藤原氏は全盛期。2度目は1186年で69歳、平家滅亡・焼討ちされた東大寺再建の資金勧請に訪ねた。西行は目的を果たしたがその後の藤原氏滅亡の戦乱で送金は途絶えた。翌年西行は73歳の生涯を閉じる。

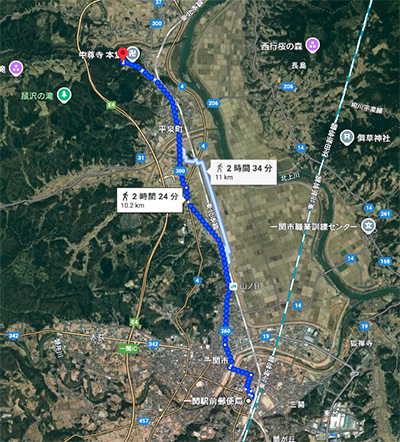

約400年後の芭蕉の行動録:1689年5月13日一関を発つ。天気晴。11時ごろ平泉に到着。高館・衣川・衣の関・中尊寺・光堂・泉城・桜川・桜山・秀衡屋敷などを見る。午後4時ごろ一関の宿に帰る。夜、入浴。

夏草や兵どもが夢の跡

五月雨の降り残してや光堂 (芭蕉・奥の細道)

江戸期には平泉中尊寺は往時からは衰微していたとされ、施設としては金色堂・覆堂と本堂のみ残っていたと言われる。芭蕉は1日で旅宿機能のあっただろう一関との間を往復している。

西行と芭蕉。明治期以前の伝統的日本詩文文化の巨人2人。

どんな無言対話を、芭蕉は西行の魂魄にこころみていたのだろうか?

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

【Basho, Longing for Saigyo, at Hiraizumi / Journey Through Japanese 5-7-5 Rhythm – 7】

After spending a day wandering through Hiraizumi, worn down by the May rains, Basho must have repeatedly let the poetry and prose of Saigyo, the great literary forerunner, echo in his mind. …

Japanese writing and literature, following the epochal introduction of the “kanji” culture from the Chinese mainland, likely developed primarily through the integration of what must have been the indigenous spoken language, “Yamato-kotoba.” The compilation of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki represented a monumental cultural undertaking pursued as a “national project.”

Within this process, the creation of hiragana and katakana marked the beginning of Japan’s unique culture of assimilation, exerting a lasting impact across all societal phenomena for generations to come. This ability to “flexibly accept and adapt for unique, practical use” could be described as quintessentially Japanese.

After the Meiji period, this trait was applied to Western civilization, enabling rapid modernization and contemporary development. However, within the Japanese language itself, the use of katakana intensified relative to the Chinese cultural sphere prevalent until the Edo period. This marked a significant shift in direction: away from the Japanese culture of poetic resonance and the 5-7 syllable rhythm, towards scientific clarity and an emphasis on prose. It can be said that Japanese literature took off from its roots in the poetic resonance-focused “literature.”

Basho lived in the early Edo period. It’s clear he was strongly drawn to Saigyo, a master of lyrical resonance from the late Heian to early Kamakura periods. One can imagine that his journey along the Narrow Road to the Deep North was likely driven by a desire to physically experience the 5-7 syllable expressions Saigyo had composed about Hiraizumi.

Today, arriving at the Kurokawa River,

My heart is deeply moved,

And my spirit grows clear.

Without a sound,

The cherry blossoms of Tabashineyama—

Beyond Yoshino,

Such beauty must exist.

(Saigyo, Shōka-shū)

The era when Saigyo (1118–1190) visited this place was the height of the Oshu Fujiwara clan’s power. Saigyo visited Hiraizumi twice. The first time, in his late twenties, his purpose was to visit the Michinoku song-beds (places associated with waka poetry) that the poet Nōin Hōshi had visited over a hundred years earlier. At this time, the Fujiwara clan of Oshu was at its zenith. His second visit was in 1186, at age 69, to solicit funds for rebuilding Tōdai-ji Temple, which had been destroyed and burned during the Heike clan’s downfall. Saigyō achieved his goal, but subsequent wars following the Fujiwara clan’s demise halted the funds. The following year, Saigyō passed away at age 73.

Approximately 400 years later, Basho’s travel record: Departed Ichinoseki on May 13, 1689. Weather clear. Arrived at Hiraizumi around 11:00. Saw Takadate, Kinugawa, Kinokawa Pass, Chusonji Temple, Kodo Hall, Izumi Castle, Sakura River, Sakurayama, and Hidehira’s Residence. Returned to lodging in Ichinoseki around 4:00 PM. Bathed at night.

Summer grasses—traces of warriors’ dreams

Leaving behind the lingering rain of May at Kōdō Hall (Bashō, The Narrow Road to the Deep North)

By the Edo period, Hiraizumi’s Chūson-ji Temple was said to have declined from its former glory, with only the Konjikidō Hall, Fukkōdō Hall, and the Main Hall remaining as structures. Bashō traveled back and forth in a single day between Hiraizumi and Ichinoseki, which likely served as lodging.

Saigyō and Basho. Two giants of traditional Japanese poetry and prose culture before the Meiji period.

What silent dialogue did Basho seek to engage with Saigyō’s spirit?

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha.

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 8月 27th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 日本社会・文化研究

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.