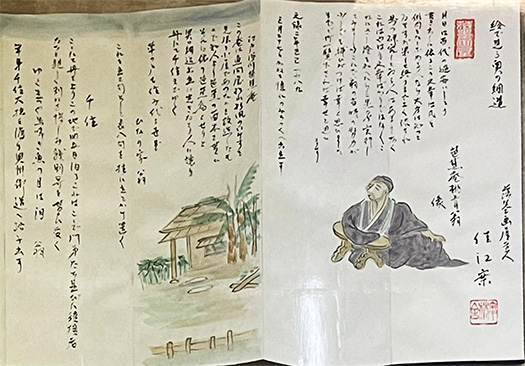

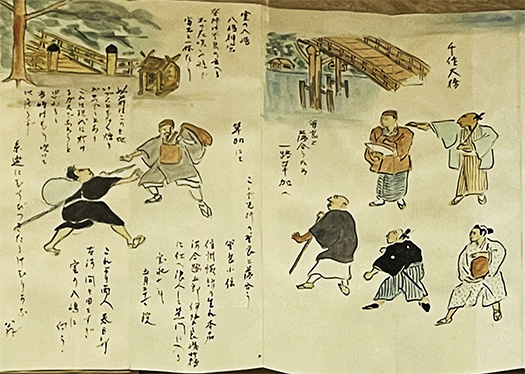

明治の日本語革命によって散文表現主体で汎社会的に文化制圧されて以降の近現代社会で教育を受け、日本語を学び使い続けてきた戦後世代人として、今回の松尾芭蕉さんへの「奥の細道」の時代差・随伴走によって、いろいろ気付かされています。

なにより花鳥風月的な日本人的「心象」の表現、その吟味作業は短文文化が日本歴史を通じてながく担ってきたのだという気付きがもっとも大きい。島国国土で四季変化がきわめて明瞭な、地球環境でも特異な条件下では、花鳥風月という精神文化性はコア部分で「わかりあい」やすい。花鳥風月の自然環境表現には、おなじ列島社会を共有する人間同士の深いコミュニケーションがあるのだと知れるのですね。北海道人は列島社会でいちばん遅れて独特の新・花鳥風月を生きているけれど、根っこの精神性は深く同期している。

そういったコミュニケーションでは、やはり「打てば響く」ようなやり取りが基本。

そのツールとして五七調はまことに適切この上ない。芭蕉さんは、句の着想を得てから内面でそれを咀嚼しながら、この花鳥風月の日本人共有知と照らし合わせながら、象徴性とか、簡潔性にこころを研ぎ澄ませていく。そういうなかから、「ここは「を」ではなく「は」にしよう」みたいな推敲に推敲を重ねて行ったことが伝わってくる。いくつか残されている「原案」と最終形との間の「苦吟」ぶりは、非常に興味深い。そしてその選択過程ははるかな後時代人である愚人にも、明白でわかりやすい。うーむと深い同意。

で、こうした心象表現においては日本語が音節において2音節と3音節で基本構成されていることが、もっとも重要な要因であると気付く。古く、大和コトバというツールがあったなかに漢字文化の導入という巨大な革命があった。八百万〜やおよろず〜分散型社会から共通的な社会を構成するに際し、中国大陸から律令制度を導入し、さらに文化規範としても神道という基盤の上に仏教導入という大革命を行った。

その「漢字」導入に際して、すぐにも「万葉かな」が必須の翻訳・導入ツールとして開発され、それが飛鳥から平安初期という時間を掛けて「ひらかな」にまで進化発展した。

安 → あ

以 → い

宇 → う

衣 → え

於 → お

このひらかな開発では、列島社会の精神性「柔軟に受容し、果断にシンプル化する」が遺憾なく発揮された。

そうなのだ、五七調日本語には、この精神性が文化として凝縮されている。芭蕉さんの「苦吟」ぶりには、この列島人のコアなこころが発露している。

そんな敬虔な思いを、感じさせていただいている。・・・

●お知らせ

拙書「作家と住空間」幻冬舎から電子書籍で発刊

お求めはAmazonで。

https://amzn.asia/d/eUiv9yO

English version⬇

The Foundations of Short-Form Culture: The Creation of Hiragana / Journey Through Japanese 5-7 Syllable Poetry – 10

From the introduction of ideographic kanji to the development of Manyōgana and hiragana for integration with Yamato Kotoba, maintaining and advancing phonetic representation. Further evolution toward a 5-7 syllable culture emphasizing phonetics. …

As a postwar generation raised in modern society—one shaped by the Meiji Japanese language revolution that imposed prose-based cultural dominance across society—and having continuously learned and used Japanese, I find myself struck by many things through this temporal gap and accompanying journey through Matsuo Bashō’s “The Narrow Road to the Deep North.”

Above all, the most significant realization is that the expression of the Japanese “mental image” of nature’s beauty—and the process of refining it—has long been carried out through a culture of brevity throughout Japanese history. In the unique conditions of an island nation with extremely distinct seasonal changes, the spiritual culture of nature’s beauty is fundamentally easy to “understand” and share. One comes to understand that within the expression of nature through flowers, birds, wind, and moonlight lies a profound communication between people sharing the same archipelago society. While Hokkaido residents live a uniquely new form of this ‘flowers, birds, wind, and moonlight’ culture, the most delayed within the archipelago society, their fundamental spirituality is deeply synchronized.

In such communication, the basic principle remains an exchange where “if you strike, it resonates.”

The 5-7 syllable structure is truly the most appropriate tool for this. After conceiving a verse, Basho would chew it over internally, comparing it against this shared Japanese knowledge of nature’s beauty, sharpening his focus on symbolism and conciseness. You can sense him refining it through layer upon layer of revision, thinking things like, “Here, let’s use ‘は’ instead of ‘を’.” The agonizing deliberation evident between several surviving “drafts” and the final forms is profoundly fascinating. And this selection process remains clear and understandable even to a fool like me, living so far in the future. Hmm… I deeply agree.

And in this kind of mental imagery expression, I realize the most crucial factor is that Japanese is fundamentally structured around two-syllable and three-syllable units. Long ago, within the tool that was Yamato Kotoba, there occurred the enormous revolution of introducing Chinese characters. Transitioning from a dispersed society of Yaoyorozu (eight million deities) to a unified society, Japan introduced the Ritsuryō system from the Chinese mainland. Furthermore, as a cultural norm, it underwent the great revolution of introducing Buddhism upon the foundation of Shinto.

Upon introducing “kanji,” ‘Manyōgana’ was immediately developed as an essential translation and introduction tool. Over time, spanning from the Asuka to the early Heian periods, it evolved and developed into “hiragana.”

This development of hiragana fully demonstrated the archipelago society’s spirituality: “flexibly accepting and decisively simplifying.”

Indeed, this spirit is culturally condensed within Japanese poetry’s 5-7 syllable structure. Basho’s agonizing “kugin” reveals the core spirit of the Japanese people.

I feel deeply moved by such reverent sentiment…

●Notice

My book “Writers and Living Spaces” published as an e-book by Gentosha

Available on Amazon.

Posted on 8月 30th, 2025 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 未分類

コメントを投稿

「※誹謗中傷や、悪意のある書き込み、営利目的などのコメントを防ぐために、投稿された全てのコメントは一時的に保留されますのでご了承ください。」

You must be logged in to post a comment.