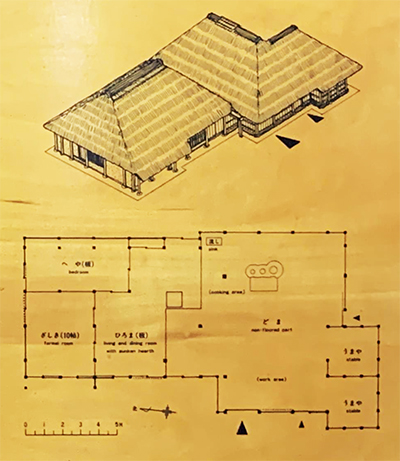

分棟という、2棟の寄棟建物が軒を接して建てられた住宅を見てきた。

本日は外周部、外観的にいくつかの気付きを。

古民家というと、建築用材と手間コストの合理性で外観が決まることから

おおむねシンプルな形状が一般的ですが、

この分棟は各棟はシンプルだけれど、その組み合わせが

たまたまこういう風に組み合わせた、という一期一会感がある。

上の写真では右端の「馬屋」突き出し部分も含めると

外形的に「雁行」を見せていて、ハッとするほど変化に富んでいる。

雁行というのは、貴族や武家などの支配階級の住居で

庭との関係での眺望性最優先ということから出てきたものだと思うけれど、

そのルーツは案外この「分棟」がイマジネーションを提供したのかも知れない。

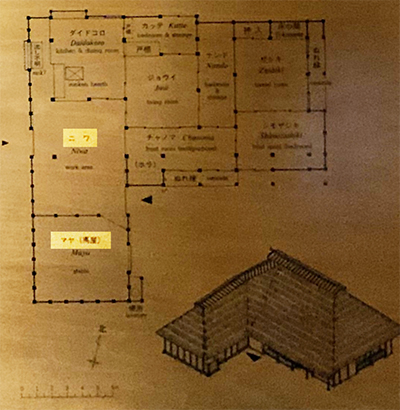

その下の写真は、現在川崎市の日本民家園に移築保存される前の茨城県での

農家住宅だった当時の佇まいであります。

右側の「土間棟」が主屋に対して手前側がせり出していて

側面にも出入り口が開けられている。

農事作業空間としての土間棟の機能性豊かな様子が偲ばれます。

屋根頂部には煙りだしも見られて、能動的な空間性が表れている。

主屋側では手前が南面している。その陽だまり空間で屋根に対して建物が

ややセットバックして大きな屋根が覆い被さる、半外空間を形成しています。

あるいは縁台などが置かれた空間だったのか、

座敷へ上がる入口としても機能していたのかと思われる。

そうした使い勝手の間取り構成を寄棟の大屋根がおおらかに包み込んでいる。

「外縁」とでもいえる空間への意識が日本人には強いのでしょうね。

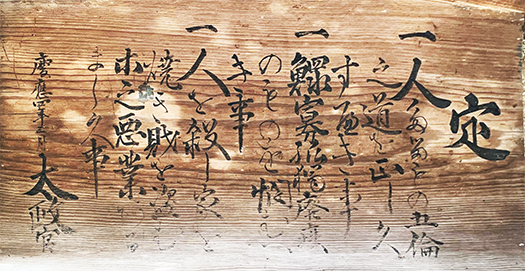

この写真は座敷の奥のあかり取り窓。

こういった開口部では古民家の場合、だいたいは戸袋が付属して

板戸が雨戸として、雨水対応・寒さ対策・防犯対策で仕込まれるケースが多いけれど、

この開口部にはそうした板戸収納がないので、常時このような障子1枚で、

紙一枚で外部と接していたと思われる。

室内側のこの開口部写真は下のもの。

現代住宅では開口部は見慣れた造作だけれど、古民家では

防寒のことも考え合わせれば、こういった仕様はかなり勇気がいるものだったかも。

建築としては隙間だらけで大差はないが、しかし雨戸と障子では心理的に大きく違う。

しかしそういう断熱欠損は別として、こういう開口部の存在は

ウチとソトの結界意識の上では、重要な心理ファクターであったことは疑いない。

位置的には「座敷」に開けられた開口部であり、来客などをもてなす造作として

機能させていたものだろうと思う。

鄙の家だけれど花鳥風月的な文化装置もあるんだよ、的な。

窓・開口部とは外部景観を「切り取る」額縁という文化要素だっただろう。

わたしも60年前ころの少年期、函館の伯父宅に遊びに行ったとき、

とびきりの床の間・縁側付きの座敷で寝させられた経験がつよく印象に残っている。

そしてそこが立派なしつらいだけれど強烈に寒かったことも憶えている(笑)。

日本人は「やせ我慢での接遇」に亭主も客人も慣れていたともいえるだろうか。

もちろん季節のいいときには最適化された日本空間文化受容にはなる。

寒いときにはそれを思い浮かべて「耐え忍べ」と。

English version⬇

[Hitachi branch building / appearance, form / good Japanese house ㉖-8]

I have seen a house built with two hipped roofs called a branch building in contact with the eaves.

Today, I noticed some things on the outer circumference and appearance.

When it comes to old folk houses, the appearance is determined by the rationality of building materials and labor costs.

Generally, a simple shape is common,

Each building is simple, but the combination is

There is a once-in-a-lifetime feeling that it happened to be combined in this way.

In the photo above, including the protruding part of the “Baya” on the far right

The appearance is “Gankou”, and it is surprisingly varied.

Gankou is a residence of the ruling class such as aristocrats and samurai.

I think it came from the fact that the view is the highest priority in relation to the garden.

Its roots may have been unexpectedly provided by this “branch building”.

The photo below is in Ibaraki prefecture, before it was relocated and preserved in a Japanese folk house in Kawasaki City.

It looks like a farmhouse at that time.

The “Doma Building” on the right side is protruding from the main building.

There is also a doorway on the side.

It is reminiscent of the highly functional appearance of the Doma Building as an agricultural work space.

Smoke is also seen on the roof top, showing an active spatiality.

On the main building side, the front is facing south. In that sunny space, the building is against the roof

It forms a semi-outer space with a slightly setback and a large roof covering it.

Or was it a space where a pedestal was placed?

It seems that it also functioned as an entrance to the tatami room.

The large roof of the hipped roof gently envelops such a convenient layout structure.

I think Japanese people have a strong awareness of the space, which can be called the “outer edge.”

This photo is the light window in the back of the tatami room.

In the case of an old folk house, these openings usually come with a door pocket.

Itado is often used as a shutter for rainwater, cold weather, and crime prevention.

Since there is no such board door storage in this opening, you can always use one such shoji.

It seems that he was in contact with the outside with a piece of paper.

The photo of this opening on the indoor side is below.

In modern houses, the openings are familiar, but in old houses

Considering the protection against the cold, these specifications may have been quite courageous.

There are many gaps in the architecture, so there is no big difference, but even so, there is a big psychological difference between shutters and shoji.

But apart from such insulation defects, the existence of such openings

There is no doubt that it was an important psychological factor in the sense of barrier between Uchi and Soto.

Positionally, it is an opening opened in the “Zashiki”, and as a feature to entertain visitors, etc.

I think it was working.

It’s a redneck house, but it also has a cultural device like Kacho Fugetsu.

When I went to visit my uncle’s house in Hakodate when I was a boy about 60 years ago,

The experience of being laid down in a tatami room with an exceptional alcove and veranda left a strong impression on me.

And I remember that it was really hard, but it was extremely cold (laughs).

Is it possible to say that the Japanese are accustomed to “hospitality with thin patience” for both the host and the guests?

Of course, when the season is good, it will be an optimized acceptance of Japanese space culture.

When it’s cold, think of it and say, “Be patient.”

Posted on 3月 25th, 2021 by 三木 奎吾

Filed under: 住宅マーケティング, 日本社会・文化研究 | No Comments »